Beehives from Five Seed Farm and Apiary, one of the farms expected to begin production on Baltimore city land in 2012. Photo: Courtesy of Five Seed Farm and ApiaryCities all over the country are addressing the lack of access to fresh and healthy food on the part of their residents, but few are in as much of a bind as Baltimore.

Beehives from Five Seed Farm and Apiary, one of the farms expected to begin production on Baltimore city land in 2012. Photo: Courtesy of Five Seed Farm and ApiaryCities all over the country are addressing the lack of access to fresh and healthy food on the part of their residents, but few are in as much of a bind as Baltimore.

Like Detroit, and other cities known for their class and race disparity, Baltimore has been losing population and gaining vacant land at a fast pace in recent decades. The result is vast swaths of neighborhoods located far from grocery stores. Baltimore gave itself a D on its own 2010 Health Disparities Report Card, which found that 43 percent of the residents in the city’s predominantly black neighborhoods had little access to healthy foods, compared to 4 percent in predominantly white neighborhoods. Meanwhile, more than two-thirds of the city’s adults and almost 40 percent of high school students are overweight or obese.

In other words, the situation is a dire one. But it’s not all bad news; in fact, the city of Baltimore is going to great lengths to make a change.

Speaking on a panel at the recent Community Food Security Coalition Conference in Oakland, Calif., Abby Cocke, of Baltimore’s Office of Sustainability, and Laura Fox, of the city health department’s Virtual Supermarket Program, outlined two approaches to address the city’s food deserts. Both were presenting programs that have launched since Grist last reported on Baltimore’s efforts to address food justice. And both programs come under the auspices of The Baltimore Food Policy Initiative, a rare intergovernmental collaboration between the city’s Department of Planning, Office of Sustainability, and Health Department. They also show how an active, involved city government and a willingness to try new ideas can change the urban food landscape for the better.

According to Cocke, Baltimore’s Planning Department has a new mindset. She calls it a “place-based” model. “In the past,” she says, “growth was seen as the only way to improve the city, but we’re starting to look at ways to make our neighborhoods stronger, healthier, and more vibrant places at the low density that they’re at now.”

Intercropping farms within the urban landscape

In cities like Oakland — where well-known urban farmer Novella Carpenter was slapped with a large fine recently, resulting in a public push for changes to the zoning laws — shifts in urban policy have been largely reactive. Other cities, like Detroit, have taken a hands-off approach. Thanks to Baltimore’s Office of Sustainability, however, the city is actively encouraging the creation of small entrepreneurial farms on vacant lots to bring more healthy fresh food to city residents.

In 2010, planning officials met with urban farmers to find out what they would need to grow food in the city. Planners mapped out 20 publicly owned parcels (ranging from one to 12 acres) that met the farmers’ criteria. City officials then encouraged experienced commercial and nonprofit groups to submit a business plan. Of the 10 initial responses, four commercial farms — including Five Seeds Farm and Seed and Cycle — and one nonprofit, Real Food Farm, were qualified to start farming.

The parcels will be leased to the would-be farmers for a mere $100 a year, and the city will make start-up capital available for those who need it. Baltimore is also rewriting its entire zoning code, one major goal of which is to facilitate farming within city limits. In addition to making its citizens healthier, says Cocke, the city hopes to “transform vacant lots, increase environmental awareness among its citizens, create green jobs, and raise its profile as a leader.”

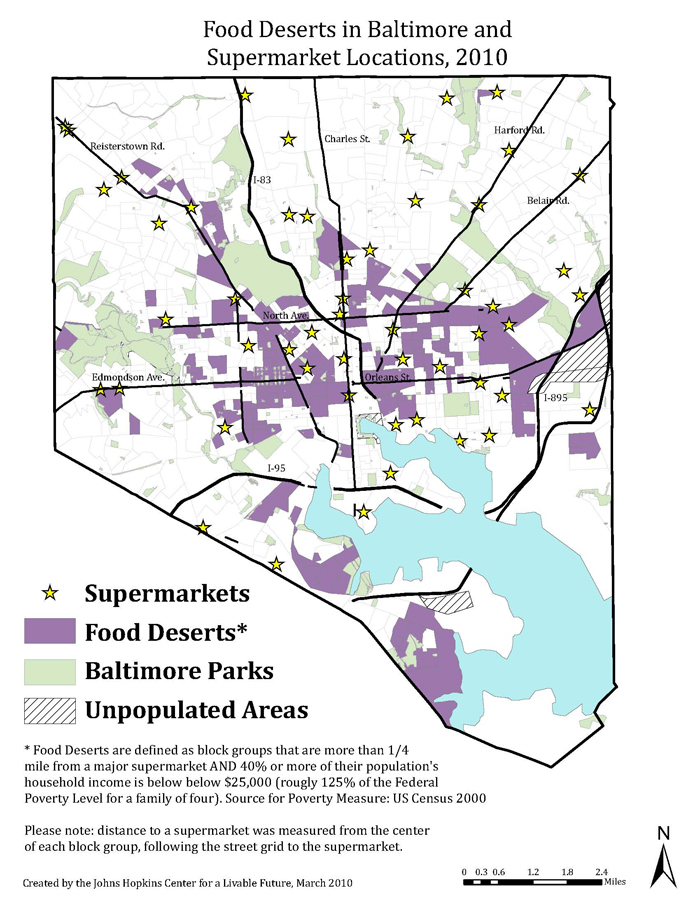

Image: Center for a Livable FutureBringing the supermarket to libraries and other public spaces

Image: Center for a Livable FutureBringing the supermarket to libraries and other public spaces

Urban farming is a useful way to make more people aware of where their fruit and vegetables comes from, but it can only provide so much food. That’s where Baltimore’s Virtual Supermarket program — a creative public-private partnership that utilizes the city’s libraries to bring fresh groceries to remote neighborhoods — enters the picture.

According to Fox, the original idea was to launch the program in churches in underserved areas. But city officials quickly found that most people didn’t feel comfortable going into unfamiliar churches. Not to be deterred, and recognizing a good idea, the city began looking at other easily accessible neighborhood spaces, and eventually settled on public libraries.

Working with The Center for a Livable Future at nearby Johns Hopkins University, the health department conducted a mapping project to target neighborhoods with no access to fresh food, low vehicle ownership, low income, and high mortality rates from diet-related diseases. They found that as much as 18 percent of Baltimore qualifies as a food desert, using these criteria. (This data is the basis of the city’s first official “food desert map,” which will be released in January 2012).

Partnering with Santoni’s, a local, family-owned grocery chain, the city launched Virtual Supermarket in March 2010 in two public libraries. Users place orders from the city’s free-to-use library computers, and Santoni’s staff members deliver the food. Customers can pay with EBT cards, cash, or credit/debit cards.

Today the program includes three libraries and one school, and its success has enabled the city to hire a full-time community organizer to recruit potential customers at senior centers and public housing complexes. To date, 150 different customers have made 700 orders.

Although the city prohibits tobacco, it doesn’t regulate what types of foods people can buy. Nonetheless, 60 percent of the Virtual Supermarket customers polled reported that their diets have improved. Most importantly, according to Fox, the program keeps Baltimore residents from having to travel an hour by bus to the nearest store, or pay to take one of the numerous unofficial cabs that line up outside the city’s grocery stores. She says she sees it as a “health equity program,” adding, “why should someone have to pay $15 to get their groceries home in a cab when someone in a wealthier neighborhood who owns a car would pay 25 cents?”

What’s next for Baltimore? For one, the city is upping its focus on cooking. They’ll soon be staging cooking demonstrations at farmers markets and other locations, and launching a program to get citizens talking to their neighbors about nutrition and cooking.

Last March, Baltimore also became one of the first cities in America to hire a full time Food Policy Director. Holly Freishtat works out of the Office of Sustainability in the Department of Planning. As Fox sees it, embedding healthy food policy into the planning department makes complete sense. After seeing some city residents endure an ongoing ordeal simply to get fresh food on their tables, she says, “Where you live affects your whole being.”