Everyone knows that the country got gobsmacked by hurricanes last year. But if you rely on mainstream media for news, you might not know that climate change had anything to do with those storms or other extreme weather events — unless you’ve recently paid close attention to Al Roker.

Climate scientists tell us that as the climate warms, hurricanes will get more intense. Yet the major broadcast TV news programs mentioned climate change only two times last year during their coverage of the record-breaking hurricanes (yes, two times). The climate-hurricane link came up once on CBS, once on NBC, and not at all in the course of ABC’s coverage of the storms, Media Matters found. All in all, major U.S. TV news programs, radio news programs, and newspapers mentioned climate change in just 4 percent of their stories about these devastating hurricanes, according to research by Public Citizen.

So it’s probably no surprise that many major media outlets also neglected to weave climate change into their reporting on last year’s heat waves and wildfires.

Will coverage be any better this year?

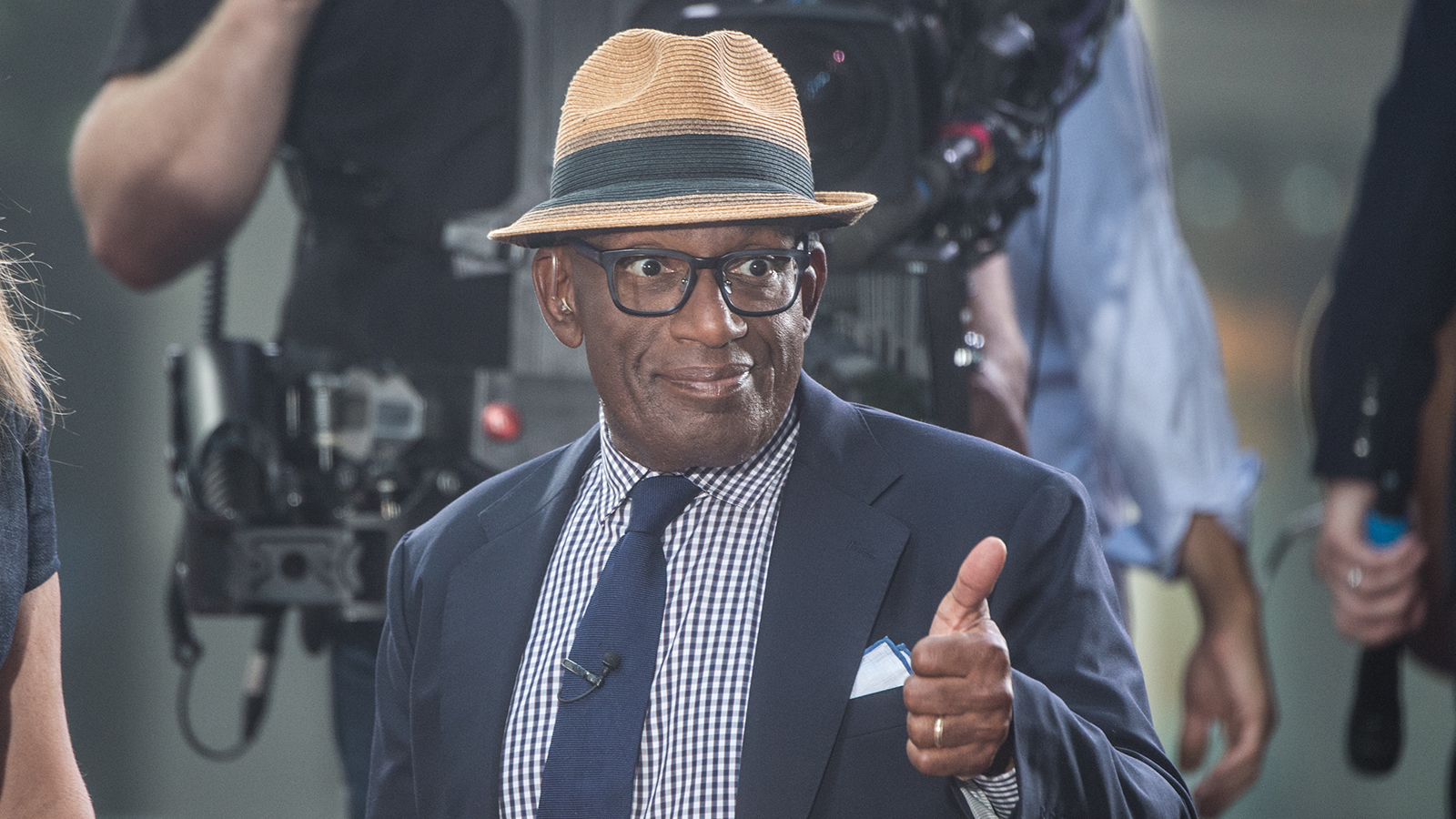

Al Roker has given us reason to feel slightly optimistic. Last week, Roker, the jovial weather forecaster on NBC’s Today show, demonstrated one good way to put an extreme weather event into proper context. While discussing the devastating flooding that recently hit Ellicott City, Maryland, he explained that heavy downpours have become more common in recent decades thanks to climate change, using a map and data from the research group Climate Central to support his point:

[protected-iframe id=”eb9001366aeb25e90a4e3ed3613441da-5104299-128770340″ info=”https://www.mediamatters.org/embed/220318?embed_source=jwplayer” width=”480″ height=”360″ frameborder=”0″ class=”video-embed” scrolling=”no” allowfullscreen=””]

As we roll into summer — the start of the season for hurricanes, wildfires, droughts, and heat waves — that’s just the kind of connect-the-dots reporting Americans need.

The New York Times helped set the scene with a map-heavy feature highlighting places in the United States that have been hit repeatedly by extreme weather. “Climate change is making some kinds of disasters more frequent,” the piece explained, and “scientists also contend that climate change is expected to lead to stronger, wetter hurricanes.”

It’s one thing to report on how climate change worsens weather disasters in general, as the Times did in that piece, but much more rare for media to make the connection when they cover a specific storm or wildfire. Roker did it, yet many other journalists remain too squeamish. They shouldn’t be; science has their back.

In addition to what we know about the general link between climate change and extreme weather, there’s a growing body of peer-reviewed research, called attribution science, that measures the extent to which climate change has made individual weather events more intense or destructive.

Consider the research that’s been done on Hurricane Harvey, which dumped more than 60 inches of rain on the Houston area last August. Just four months after the storm, two groups of scientists published attribution studies: One study estimated that climate change made Harvey’s rainfall 15 percent heavier than it would have been otherwise, while another offered a best estimate of 38 percent.

Broadcast TV news programs failed to report on this research when it came out, but they should have. And the next time a major hurricane looms, media outlets should make note of these and other studies that attribute hurricane intensity to climate change. Scientists can’t make these types of attribution analyses in real time (at least not yet), but their research on past storms can help put future storms in context.

Of course, in order to incorporate climate change into hurricane reporting, journalists have to report on hurricanes in the first place. They failed miserably at this basic task when it came to Hurricane Maria and its devastation of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Maria got markedly less media coverage than hurricanes Harvey and Irma, according to analyses by FiveThirtyEight and researchers from the MIT Media Lab. The weekend after Maria made landfall in September, the five major Sunday morning political talk shows spent less than a minute altogether on the storm. And just last week, when a major new study estimated that Maria led to approximately 5,000 deaths in Puerto Rico, as opposed the government’s official death count of 64, cable news gave 16 times more coverage to Roseanne Barr’s racist tweet and her canceled TV show than to the study.

Hurricane Maria overwhelmingly harmed people of color — Puerto Rico’s population is 99 percent Latino, and the U.S. Virgin Islands’ population is 98 percent Black or African-American — so it’s hard not see race as a factor in the undercoverage of the storm.

The lack of reporting on Maria sets a scary precedent, as climate disasters are expected to hurt minority and low-income communities more than whiter, wealthier ones. Unless mainstream media step up their game, the people hurt the most by climate change will be covered the least.

Ultimately, we need the media to help all people understand that climate change is not some distant phenomenon that might affect their grandkids or people in faraway parts of the world. Only 45 percent of Americans believe climate change will pose a serious threat to them during their lifetimes, according to a recent Gallup poll. That means the majority of Americans still don’t get it.

When journalists report on the science that connects climate change to harsher storms and more extreme weather events, they help people understand climate change at a more visceral level. It’s happening here, now, today, to all of us. That’s the story that needs to be told.

Lisa Hymas is director of the climate and energy program at Media Matters for America. She was previously a senior editor at Grist.