Residents of Harris County, Texas are no stranger to heat. The swampy Houston metro area averages nearly 40 days per year with temperatures in the 100 degrees F or higher range. But, according to a pair of papers published this week, if nothing is done about climate change, many more U.S. cities could be feeling a similar kind of heat.

A report released by the Union of Concerned Scientists and a study published by the same authors in the journal Environmental Research Communications Tuesday found that the annual number of days with heat indices (the ‘feels like’ temperature that takes into account the heat and humidity levels) above 100 degrees F is expected to double by mid-century. That’s compared to temperatures between 1971 to 2000. The number of days that “feel like” 105 degrees or higher is set to triple, with the number of people exposed to “off-the-charts” temperatures growing exponentially.

What exactly is considered “off-the-charts,” you ask? Those are days with conditions so extreme that they exceed the current National Weather Service heat index range, which stops at 127 degrees F. That’s a higher heat index than what we’re currently seeing in Death Valley in July. Days like this have so far affected less than 1 percent of the U.S. by area, but by mid-century, up to a quarter of the U.S. could feel “off-the-charts” heat at least one day a year.

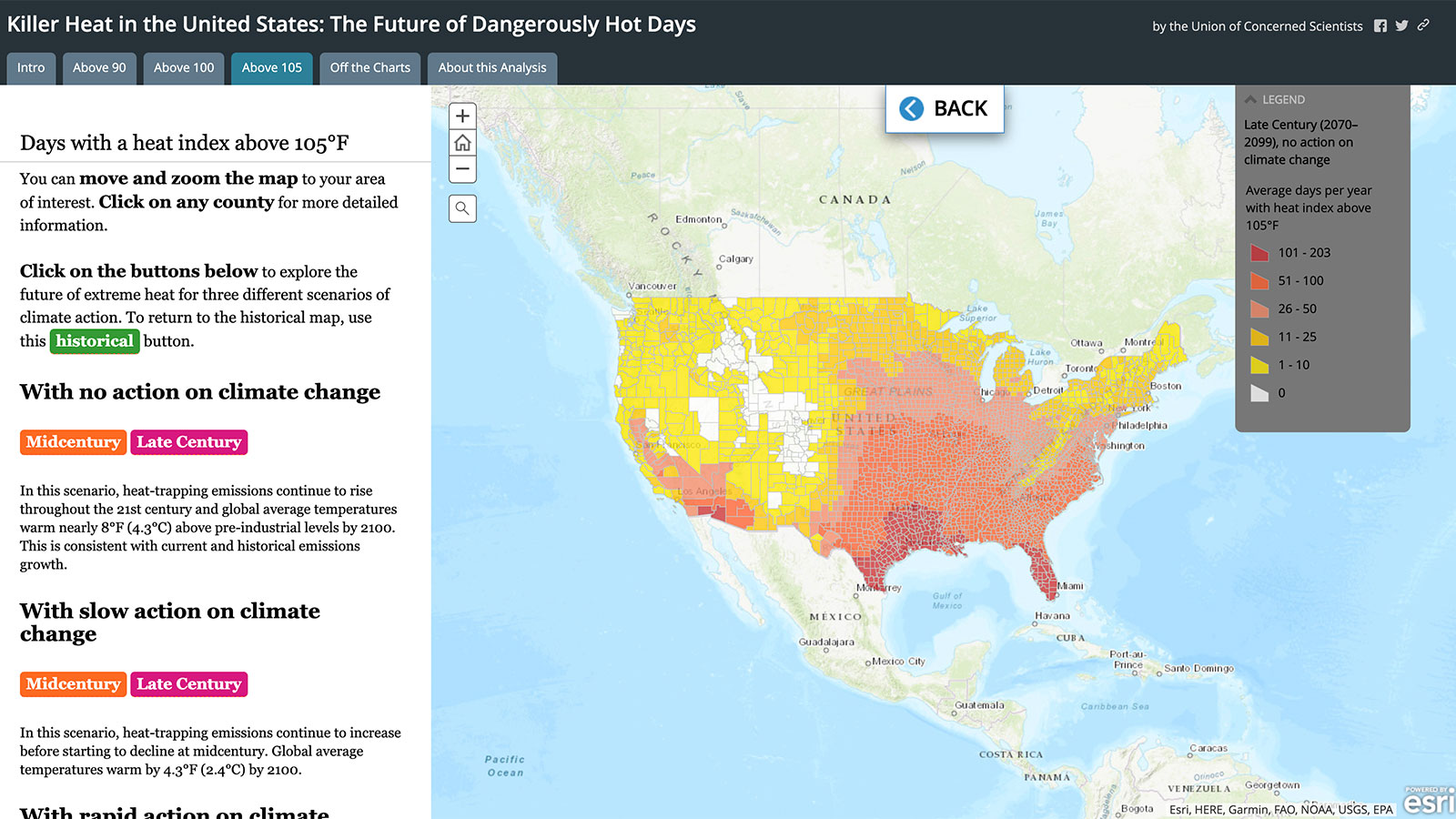

For anyone curious about how many days of scorching heat their own county might experience in the future, the study comes along with an interactive map and search tool for people to see how their own hometown could be affected depending on what level of climate action we take to avert the crisis.

The Union of Concerned Scientists

The map allows users to search how many average days per year a particular locale will experience heat indexes above 90, 100, 105, and 127 degrees F by mid-century and late-century compared to averages between 1971-2000. If that seems like a lot to navigate, simply type in your city or county into the search tool to get a summary.

As for current hotspots like Harris County, Texas, the “do nothing” heat index outlook is decidedly not good. By midcentury (defined in the study as 2036-2065), the study projects the area could experience an average of109 days per year with heat indices above 100 degrees F, compared to only 37 days historically. By late century, that count could reach 142 days with an average of 22 “off-the-charts” heat days per year.

But those ultra-high temperatures may not quite be locked in yet. If the world is able to meet the goals of the Paris climate agreement and limit global average temperatures to an increase of no more than 3.6 degrees F (2 degrees C) above pre-industrial levels, the average number of days in Harris County that feel hotter than 100 F could be reduced to 97. That’s still a lot (and note: we’re not currently on track to hit that Paris agreement target), but the study authors say changing course now could still end up saving a lot of lives across the U.S.

Extreme heat is more than just uncomfortable — it can be downright destructive. A recent study found increases in temperature correspond with spikes in violent crime. And worse, extreme heat kills more people in the U.S. each year than any other type of weather-related disaster. Children and seniors are particularly vulnerable. So are people without air conditioning and residents living in “urban heat islands,” which typically have a higher concentration of low-income folks and people of color. In places like New York, a disproportionate number of black residents have lost their lives to heat-related causes.

No matter what, it seems more extreme heat is on the way — but the frequency and length of extreme heat events still depend on how ambitiously we take on climate change. “The best ways to avoid the worst impacts of an overheated future are to enact policies that rapidly reduce global warming emissions and to help communities prepare for the extreme heat that is already inevitable,” Astrid Caldas, a senior climate scientist at UCS and report co-author, said in a statement.

“Extreme heat is one of the climate change impacts most responsive to emissions reductions, making it possible to limit how extreme our hotter future becomes for today’s children.”