This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

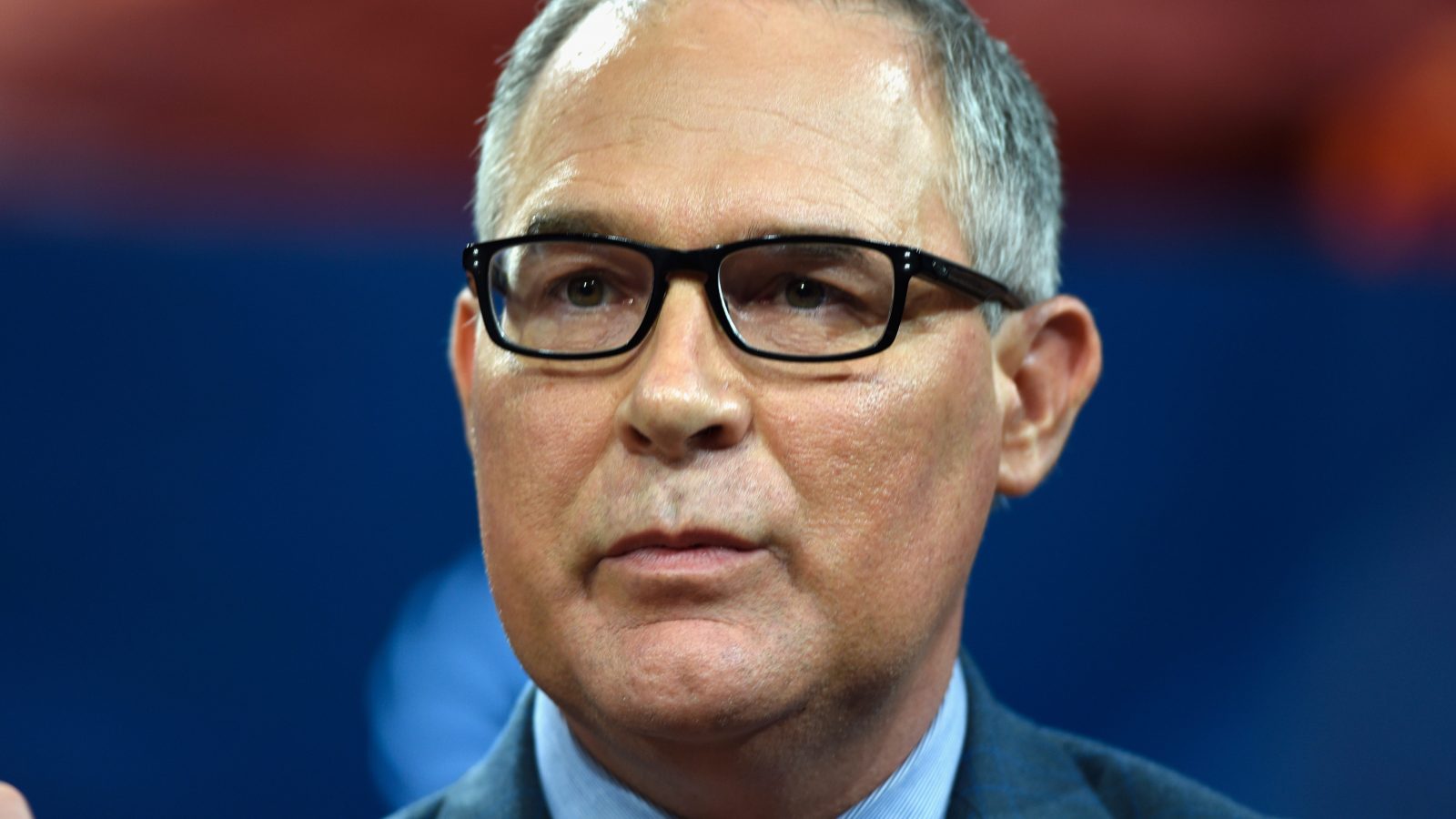

For months, the Trump administration has been quietly plotting how to repeal the Clean Power Plan, the Obama administration’s most ambitious effort to cut the nation’s carbon footprint. After weeks of speculation, the announcement came Tuesday in an agency press release where EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt claimed to be “righting the wrongs of the Obama administration by cleaning the regulatory slate.”

Pruitt signed a proposal to repeal the Clean Power Plan, which provides the agency’s justification for rolling back the power plant rule. It is also issuing an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, which former EPA staff say is a rare and unnecessary stalling tactic that solicits input from the public before the EPA even suggests its own proposal. Normally, the EPA will solicit feedback on a proposed draft, but with this, the administration provides no specific information about what it intends to do.

“It’s less than a proposal,” Natural Resources Defense Council Clean Energy and Climate Director David Doniger says. “It’s the beginning of a long, slow process as far as we can see.”

President Trump has repeatedly promised to roll back the 2015 rule, which attempts to cut carbon pollution from existing power plants by about a third from 2005 levels by requiring states to come up with their own plans to increase their mix of renewables and gas. The question was how getting rid of the rule would happen. There were several possible scenarios: One option was to succumb to climate change deniers’ demands and attempt to challenge the EPA’s finding that greenhouse gases endanger human health. The other was to give into certain business interests, like the Chamber of Commerce and National Association of Manufacturers, and replace the Clean Power Plan with a weaker proposal that would have required only minor tweaks to existing energy efficiency measures inside power plants.

It turns out Pruitt’s EPA is doing neither. It’s repealing the climate rule by kicking the can down the road. The only specific action to emerge Tuesday was to solicit public comments for what the EPA might do at some point in the future. Tuesday’s action provides further evidence that the Trump administration’s EPA is unlikely to address the driving causes of climate change.

The specific effects of Tuesday’s action, Earthjustice attorney Abigail Dillen suggests, could be that “the president and Pruitt will presumably score a few political points with their base, and maybe some coal execs will fly down to Mar-a-Lago to celebrate a symbolic victory.”

There’s plenty of disagreement on just how strong the Clean Power Plan was, given that the nation’s power plants were already halfway on their way to meeting the plan’s benchmarks when it went into effect. Politico’s Michael Grunwald wrote last fall, “The electric sector is getting so green so fast that it has already met the plan’s 2024 goal for slashing carbon emissions and its 2030 target for reducing coal use.” (New Trump-imposed obstacles in solar’s way could still change that, though.)

Nevertheless, in a landmark 2007 decision, the Supreme Court required the EPA to take action if it determined that the negative health effects from greenhouse gas emissions are scientifically proven — which they are. That decision could eventually create a legal dilemma for the EPA if it repeals the Clean Power Plan without a replacement — a problem that even the Heartland Institute, a think tank that rejects the scientific consensus on climate change, acknowledged to me.

So what’s Pruitt really trying to accomplish by Tuesday’s action?

“They will get a talking point,” former EPA attorney Joe Goffman says, which means that Pruitt and his allies can repeat their assertion that the Obama administration overreached and overestimated the benefits of the rule. Nonetheless, Goffman notes, talking points are irrelevant when considered from a legal or policy point of view, because they avoid contending with “the range of questions [on air and pollution] the agency is obligated to address.”

At the same time, Pruitt may also be factoring in his own political future. He may not want to be seen as regulating carbon pollution, even if it’s a shell of the rule, because of the likelihood he will run for office in Oklahoma.

Goffman, who is now at Harvard’s Environmental Law Program, suggests that Pruitt has no belief in regulation, “so he’s actually in a paradoxical position. If they do propose a replacement for the Clean Power Plan, what he’ll be doing is putting his signature on the proposal that will require, to some extent, that power plants address their carbon emissions.”

Meanwhile, experts note some troubling aspects of Pruitt’s justification for repeal. The 43-page draft document cited the costs of implementing the plan, without factoring in the benefits from carbon reduction. It uses “very narrow, technical arguments that allow them to evade the question of whether or not we need to be moving energetically to remove greenhouse gas emissions,” Goffman says.

For example, it discounts the global cost of carbon calculated by the EPA under the Obama administration, and it also argues that ancillary benefits from reducing lung-clogging particulate matter by switching from coal to renewables shouldn’t count. Doniger says the EPA’s new math now overestimates the costs of implementation at $33 billion, a substantially higher number than where the Obama administration put it at more than $8 billion. The Obama administration estimate still showed the Clean Power Plan to be a net plus with $34 to $54 billion in benefits to the public, as well as up to 6,600 deaths avoided annually. NRDC experts write in a blog post that Pruitt’s EPA “radically distorts the science and economics of assessing the harms of these dangerous pollutants and the benefits of curbing them, and it does so without any review or input from the scientific community.”

In Tuesday’s action, the administration takes “what is a broad policy and legal issue or set of issues and reduces it to very narrow technical arguments that allow them to evade the question of whether or not we need to be moving energetically to remove greenhouse gas emissions,” Goffman says.

The rollback will certainly be challenged in courts, where environmentalists may seek to prove that Pruitt is disregarding the Clean Air Act by not regulating carbon pollution. He will now find himself on the other side of lawsuits he often launched against the EPA when he was Oklahoma’s attorney general. New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman has already vowed to sue, and he won’t be alone when the proposed climate repeal is finalized.

There is a certain irony to the timing of the repeal. Scientists have pointed to the connection between climate change and the intensity of the recent hurricanes and California’s wildfires. Yet Pruitt dodged a question from CNN last month about the connection between climate change and devastating back-to-back hurricanes. Pruitt answered that was “very, very insensitive” to use “time and effort to address” climate change while Florida was coping with Irma’s floodwaters.