Hello and welcome. Zoya here. It is Wednesday, October 13.

Swaths of northern and central California were put under a red flag warning early this week as strong winds topping 50 miles per hour descended on the region. The Alisal Fire erupted in the Los Padres National Forest near Santa Barbara on Monday afternoon. It burned some 4,000 acres by nightfall, prompting evacuations along the Central Coast and shuttering part of Highway 101.

Pacific Gas and Electric, or PG&E, California’s power utility and the biggest electricity company in the United States, shut off power to thousands of Californians in advance of the winds in an effort to prevent its electrical equipment from starting more fires. One of the company’s transmission lines ignited the deadly Camp Fire that razed the town of Paradise in 2018 — an incident for which PG&E plead guilty for 84 counts of involuntary manslaughter. The company is likely responsible for this year’s Dixie Fire, too.

In Idaho, dry conditions are fueling active fires — there are 14 large fires burning in the state at the moment. Thirty-one other large fires are burning in California, Colorado, Montana, Oregon, Washington, Wyoming, Minnesota, and Oklahoma. Rain will move through much of the western U.S. in the next few days, which will help firefighters contain blazes.

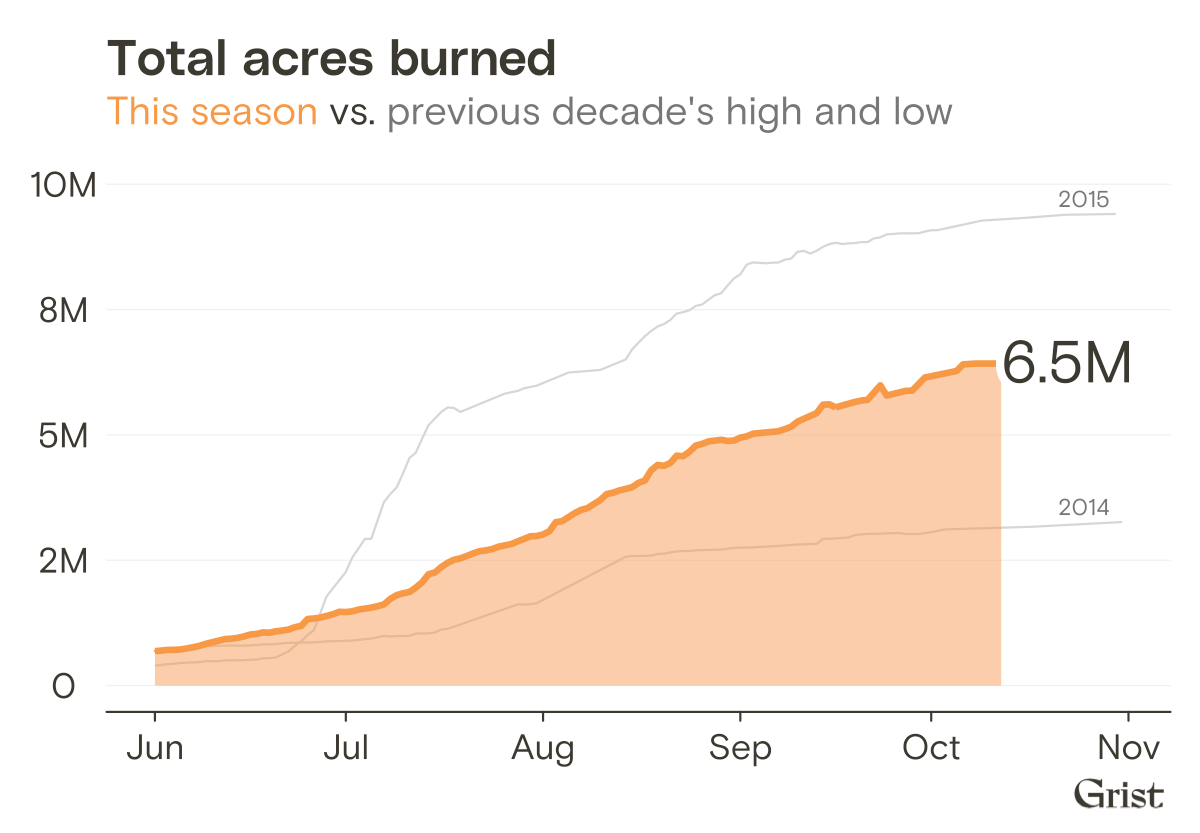

Approximately 6.5 million acres have burned so far this year and fire suppression has cost the U.S. $4.3 billion.

Data Visualization by Clayton Aldern

The growing housing crisis in California’s fire-prone communities

Hi, María Paula here, environmental justice fellow at Grist. Last week, a judge in San Diego reignited the debate about new housing development in areas of California that are prone to burning.

The judge ruled against the Jackson Pendo Development Company, which had planned to build 1,119 upscale homes, commercial storefronts, and even a school in an area outside the city of Chula Vista that has seen seven wildfires since 2003. Local fire authorities warn the region will very likely burn again in the near future.

The development, known as Adara at Otay Ranch, is the latest example of a growing problem in the California housing market: Most local and state policies prioritize fixing burned homes, imposing stricter building codes, and ensuring better evacuation routes. But many experts argue the state needs to simply stop building in fire-prone areas to begin with.

The result of those policies is that authorities, willing or unwillingly, are exacerbating the wildfire-based housing problem in California. In addition, many homeowners don’t know they’re buying in risky areas. As wildfires become more severe in the American West, many insurance companies have taken steps to reduce their losses, including refusing to renew policies for at-risk homes. According to the California Department of Insurance, in the state’s 10 most fire-prone counties, nonrenewal increased by a staggering 203 percent from 2018 to 2019.

This leaves people with few options: Use the state insurance program, known as the FAIR plan, which is extremely expensive and not very comprehensive; move out; or stay without insurance. For many low-income residents, living uninsured is their only choice.

A firefighter walks past homes in Los Angeles burnt in the Woolsey Fire in 2018. David McNew / Getty Images

For the third year in a row, California temporarily banned insurance companies from dropping homeowners and renters in several California counties affected by fires. But this, of course, is no long-term solution. According to Sarah Anderson, a professor of environmental science and management at the University of California, Santa Barbara, the ban can have a “perverse” effect on the market: It signals to homeowners and developers, like those from the Adara at Otay Ranch, that no matter the warnings about moving to fire-prone areas, the state will have their backs.

Solving the problem, explains natural resources economist Andrew Plantinga at the University of California, Santa Barbara, will require carefully looking at California’s insurance regulations. It currently states that insurers can only increase their rates based on historic losses — which makes it almost impossible to update them to reflect the rapidly growing risks of climate change.

Amy Bach, the executive director of United Policyholders, a non-profit which helps homeowners find insurance policies to secure their properties, said that relocation programs for people living in fire risky areas should be on the table as well. “People have been asking this question: ‘Should people be allowed to continue to live in these areas?’” she told me recently. “If we keep getting to this level of destruction, it is nature which is going to answer the question herself.”