If you go to a gentrifying neighborhood and ask around, or just look at Census data, you will find that the neighborhood did in fact exist before it became trendy. Its population may have been lower; it certainly would have been poorer, and probably less white. But it was inhabited. And yet the media tells us otherwise, suggesting that until new residents showed up, these neighborhoods were “a no man’s land,” still waiting to “emerge.”

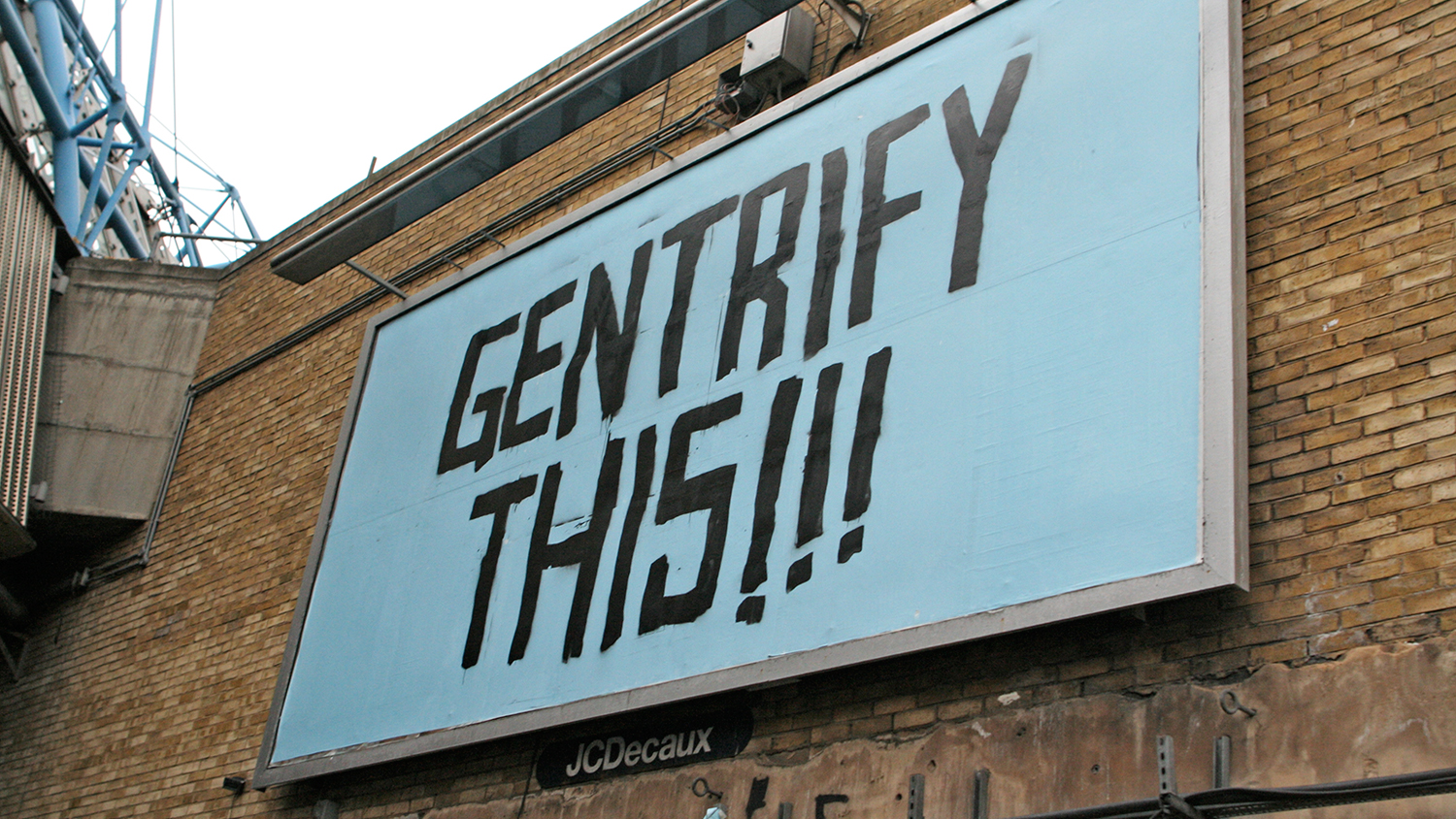

American colonialism may be a thing of the past as it’s discussed in high school history classes, but it is alive and well in U.S. cities. Just look at the language that gentrifiers use to describe their new neighborhoods, and the language used by leading publications.

At the top of Sunday’s Real Estate section, The New York Times announces, “The South Bronx Beckons.” “For decades,” the Times observes, “the lower part of the Bronx remained off the radar.” It couldn’t be detected by radar? No, that isn’t true. Well, off which radar then? The radar of low-income blacks and Latinos? No, they were living there in great numbers. It’s the birthplace of hip-hop. People knew it existed. But the only radar the Times is monitoring is that of rich, white people who live in more affluent neighborhoods.

“In the never-ending quest for reasonable rents and tolerable commutes, New Yorkers are branching out in new directions,” the Times writes. But aren’t there people who already live in the South Bronx and aren’t they New Yorkers? No, “New Yorkers” in Times-speak are rich, white professionals — couples who can pay $2,500 per month in rent, like the ones profiled in the story. They may only have lived in New York for a few years, while the South Bronx is full of lifelong natives. But the former are New Yorkers and the latter are not, according to the language of the Times. Low-income, African-American and Latino communities aren’t considered New Yorkers by the city’s leading newspaper.

There are words for this attitude: racism and classism.

“With prices in Manhattan, Brooklyn and parts of Queens now out of reach for many renters and buyers, the Bronx, particularly the South Bronx, has assumed the mantle of next frontier,” the Times continues. Ah, yes, the frontier. As you may recall, that’s where white Americans stole land from Native Americans. You’d think that with such a loaded, painful history, the word wouldn’t be deployed today to describe white settlers in search of cheaper land. But the Paper of Record has no such scruples. It heralds the arrival of colonists who have come to tame the uncharted wild.

The Times appears to get this attitude from talking to real estate industry swindlers instead of actual community members. Last year, the paper quoted a real estate agent who was marketing a development in the Gowanus section of Brooklyn by claiming it was in the neighboring, more expensive Carroll Gardens area: “These days the lines of a neighborhood are drawn by real estate agents,” she said. This attitude — that rich outsiders looking to exploit an area are the ones who decide what it is named, not the longtime residents — can best be described as imperialism. The Times did not bother to ask any community activists or residents for their thoughts on what their neighborhood is called. Indeed, the same article opened with the following sentence: “For decades, Gowanus was written off as a no man’s land.” The phrase “a no man’s land” might lead you to believe there were no residents in the area. In fact, there were more than 20,000. The Times just doesn’t count them. If its reporter passed through Gowanus without seeing a fellow yuppie or a business catering to her tastes, then she saw no signs of life at all.

I’ve been earnestly informed by people who recently moved to Crown Heights, Brooklyn, that a big chunk of it is actually now part of the more-gentrified Prospect Heights neighborhood because “the boundaries have changed.” A few upper-middle-class white people arrive and get to rename the neighborhood, apparently. But the people who have been there their whole lives, the African-American and Caribbean-American community for whom this neighborhood already has a name? They don’t get any more say than Native Americans did when the New World’s colonies were named. And so the Times recently mentioned that the border of those two areas is “a neighborhood sometimes called ProCro.” That’s a false assertion. No one ever calls western Crown Heights “ProCro,” except perhaps for real estate industry scam artists who don’t respect the Crown Heights community and credulous reporters who don’t bother to check whether anyone actually from the area uses this grating neologism.

This attitude is hardly unique to one news outlet or to New York City. In Washington, D.C., local public radio station WAMU reported in May that in recent years, “developers started purchasing single-family homes in emerging neighborhoods like Columbia Heights, the H Street NE corridor, Bloomingdale and Petworth.” The word “emerging” implies that these neighborhoods did not previously exist. In fact, they have existed for a century, it’s just that in the last few decades the residents were neither rich nor white.

Ironically, some of these same stories go on to discuss current residents’ fears of gentrification and displacement, and the neighborhoods’ current struggles with issues such as crime and pollution. The Times notes in its Sunday feature, “Nearly 40 percent of residents in the South Bronx live below the poverty line, and community activists worry that the area’s most vulnerable residents could be left behind in the rush to develop. … [T]he problems that have long plagued the South Bronx have not gone away. The area lacks access to open space, many of the schools are failing and air pollution contributes to high asthma and allergy rates among children.” And in its article last year on the Gowanus neighborhood, the Times described the Superfund-listed Gowanus Canal’s legacy of toxic industrial pollution and how it fills up with stinky sewage during heavy rains, saying these “unyielding realities have kept [the neighborhood] off the map.” Gowanus is, in fact, found on maps. This is just another instance of the paper figuratively erasing a neighborhood’s pre-gentrification existence.

These neighborhoods are not blank slates — they have complex histories. They became cheaper and poorer than their neighbors, sometimes with empty lots ripe for development, because of political decisions. In some cases, like with some rowhouse neighborhoods in D.C., it was the same set of policies that encouraged suburban sprawl, such as preferential tax treatment for home mortgages and heavy subsidies for car-centric development. In others, like Gowanus and parts of the South Bronx, they were the areas society stuck with our auto and industrial detritus: warehouses, auto body shops, waste transfer stations, and bus depots. Entire blocks were razed and replaced with towers-in-a-park-style public housing.

Until recent years, no one expected these neighborhoods to gentrify because no one predicted the massive shift in preference among young professionals toward walkable urbanism. Now, many of the young and affluent are so desperate to avoid the soul-crushing banality of suburbia that they would rather live next to a toxic waste dump that smells, literally, like shit.

If we put in place the right policies to allow new market-rate housing development and require affordable low-income housing, new residents could be absorbed into these areas, existing residents could continue to live in them, and this would all be good news for the environment because it would lead to more of the population living in the inner cities. If more people live in the South Bronx rather than moving to the suburban fringe, their carbon footprints will be lower, thanks to driving less and living in more energy-efficient apartment buildings rather than detached houses with garages and lawns. But in the past, governments haven’t done enough to protect existing communities and they have restricted new development, so gentrification has mostly led to the displacement of lower-income residents through rising prices.

There is nothing wrong with news outlets reporting on these ongoing transformations, or with noting that affluent professionals weren’t looking for housing in these neighborhoods a few years ago. But heralding these population shifts as if they were filling a void — as if places lie fallow until a certain type of resident arrives — reflects exactly the sort of attitude that leads to displacement instead of integration.