In the 17th, 18th, and early 19th centuries, European settlers stole a lot of land from Native Americans. They killed them, they cheated them, and they robbed them of most of the continent. But they made one mistake. Back then good land was fertile land for growing crops. The Great Plains and interior West — dry, dusty, freezing cold in winter and broiling hot in summer — had little to offer.

Now, however, the Europeans and their descendants lust for oil and gas to provide electricity, heat, and fuel for internal combustion engines. And guess where a lot of it is to be found? On tribal lands, or near them, requiring pipes, tracks, or roads to be laid through them.

You can see where this is going. Corporations and pliant local officials — today’s equivalent of conquistadors and European crowns — are trying to gain control of what’s left of indigenous peoples’ land.

“There are more than 600 major resource projects worth $650-billion planned in Western Canada over the next decade but relations with First Nations may be a major hurdle for those developments,” reports the Toronto Globe and Mail.

The Fraser Institute, a conservative Canadian think tank, has issued a report fretting that oil pipelines may not be built through tribal lands owing to First Nations’ (the Canadian term for Native Americans) opposition. Fraser proposes highlighting the potential economic benefits of the projects. Canadian First Nations, just like Native American communities, suffer from disproportionately high unemployment and poverty. However, they may also lack the educated workforce necessary to fill some of the jobs.

Just south of the border in North Dakota, two members of the MHA Nation, a federation of three Native American tribes, are waging a lonely battle to protect their community from the effects of oil exploration. According to the Minneapolis Star-Tribune, “There are 22 drilling rigs, 979 active wells and 148 on the verge of completion within the reservation’s boundaries — cranking out a quarter-million barrels a day and earning the tribes $1 million a month.” So, understandably, not many residents of this impoverished, isolated community oppose drilling.

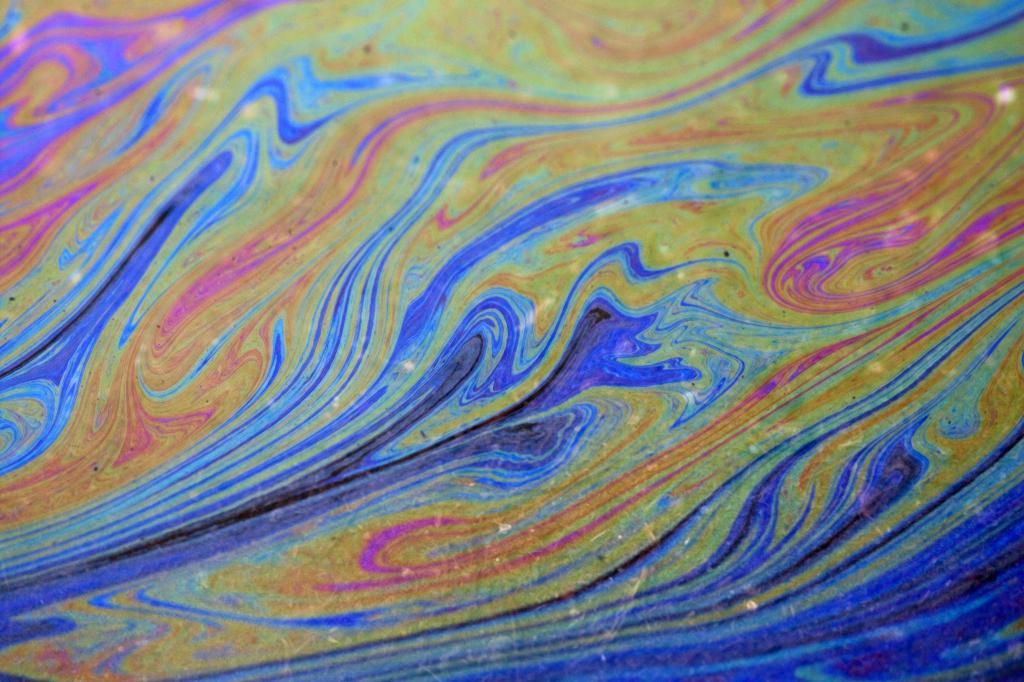

But the dangers from drilling are significant, and only just beginning to come to light. Oil leaks are killing crops in the state, and rendering land and water unusable. The Star-Tribune reports:

A Tioga farmer 80 miles north of Mandaree discovered a spill from a busted pipeline that oozed more than 20,000 barrels of oil on his wheat fields. It is one of the largest spills in North Dakota history, and neither regulators nor the Tesoro pipeline company informed the public for 11 days.

In October, a leak in an underground line sent 150 barrels of disposed salt water leaching onto U.S. Forest Service land west of Dickinson. Weeks later, a Nov. 7 explosion ignited 13 tanks and spilled 2,700 barrels of salt water and oil southwest of Alexander.

All told, North Dakota recorded 300 pipeline spills the past two years, many minor, without alerting the public.

Environmental damages are not the only downside to living near an oil or natural gas boom. Drilling boosters like the Fraser Institute talk up the economic benefits, but along with the influx of money and people chasing it comes traffic, escalating real estate prices, and violence. The New York Times reports that western North Dakota and eastern Montana, where the oil industry has experienced explosive growth in recent years, are currently suffering from all of those problems:

Crime has soared as thousands of workers and rivers of cash have flowed into towns, straining police departments and shattering residents’ sense of safety. …

[R]eports of assault and theft have doubled or even tripled, and the police say they are rushing from call to call, grappling with everything from bar brawls and shoplifting to kidnappings and attempted murders. Traffic stops for drunken or reckless driving have skyrocketed; local jails are spilling over with drug suspects.

Last year, a study by officials in Montana and North Dakota found that crime had risen by 32 percent since 2005 in communities at the center of the boom. In Watford City, N.D., where mile-long chains of tractor-trailers stack up at the town’s main traffic light, arrests increased 565 percent during that time. In Roosevelt County in Montana, arrests were up 855 percent, and the sheriff, Freedom Crawford, said his jail was so full that he was ticketing and releasing offenders for minor crimes like disorderly conduct.

Native American communities considering the economic benefits of oil and gas development will have to weigh them against all these drawbacks.

And, indeed, indigenous groups are increasingly resisting local governments and landowners who are trying to sell them out.

In New Brunswick, the government sold fracking leases to a Texas company over local protest led by the Mi’kmaq indigenous people from the Elsipogtog First Nation. Even though the courts are siding with the provincial government, demonstrations continue, slowing operations. And time is money.

In the U.S., Native Americans are a vibrant part of the opposition to the Keystone XL pipeline.

But perhaps indigenous groups have the most opportunity for disrupting oil and gas projects in Western Canada, where First Nations have to be consulted about development, and compensated for it. Some First Nations groups in the area support planned pipelines and other projects, some don’t. But it is up to them, the people who have been there longest and have the most to lose — as it should be.