A few months ago, the U.S. and 195 other countries signed this thing in Paris in which all parties involved kind of sort of agreed to stop messing with the world’s climate. It was very exciting.

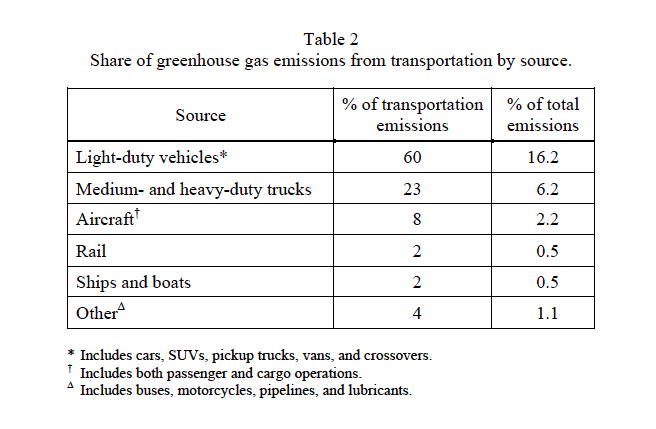

So what if we, as Americans, were going to join in as individuals in order to help the U.S. meet its emissions goals? What would we do differently? Two researchers at the University of Michigan’s Transportation Research Institute, Michael Sivak and Brandon Schoettle, recently set out to answer those questions. (Here is the abstract of their report.) Their conclusion: The largest single source of greenhouse gas emissions is making things (industry, clocking in at 29 percent of greenhouse gas emissions). After that, there’s moving people and things around (transportation, 27 percent), then the energy we use at home (17 percent) followed by the energy used by non-industrial businesses (17 percent) and the energy used in agriculture (10 percent).

Most of this energy is stuff that you don’t have any control over: If you are looking at a row of lawn chairs at the store, you don’t have any way of knowing how much energy it took to produce each one. You cannot, on a personal level, decide to have your contact-lens solution delivered to your local pharmacy by cargo bicycle instead of long-haul trucker.

So, given the imperfections of this world, what is a lone wolf such as yourself to do? Here are some conclusions gleaned from this study:

1. Buy the most fuel-efficient car you can afford, then drive it as little as possible

You might notice that Sivak and Schoettle don’t even consider the option of going without a car — even though their own graph suggests that, if having an efficient car is good, having none at all is even better:

To be sure, many people live in cities and work at jobs where living without a car is virtually impossible — and these are the people who this report is written for.

To be sure, many people live in cities and work at jobs where living without a car is virtually impossible — and these are the people who this report is written for.

Currently, the average car on the road gets about 21.4 miles per gallon. If that went up to just 31 mpg, Sivak and Schoettle claim that the amount of carbon that the U.S. emits would drop by 5 percent — as long as we didn’t go crazy and drive a lot more. If the average fuel economy rose to 56 mpg, total U.S. emissions would be reduced by 10 percent.

That said, I would like to see Sivak and Schoettle have a conversation with my (very nice) Motor City-born mom about why she should get the most fuel-efficient car she can afford when she loves her damn Jeep and gas right now is less than $2 a gallon. Since they both live in Michigan, maybe they have already.

2. Drive your fuel-efficient car until it’s so old that it turns into dust — actually, use everything you own for so long that it turns into dust

The average age of a car on the road right now is 11.5 years. The average 3,000-pound car takes the equivalent of 260 gallons of gasoline to make. It’s not like you can compare among different manufacturers to see which one is the most energy-efficient carmaker any more than you can compare lawn-chair makers or cellphone manufacturers.

But unless you’re trading it in for something that is significantly more energy efficient than what you have already, keep the old stuff around. That goes for cars, clothes, shoes, remodeling your kitchen, and so on and so forth. There is no law requiring you to buy a new cellphone every two years, and though that’s what we do in the U.S., in other countries people keep them much longer.

3. Drive your fuel-efficient car like it is a leaf on the breeze

According to Sivak and Schoettle, frequent hard stops and rapid acceleration have a dramatic effect on fuel efficiency. They assume that the average driver can reduce overall fuel consumption by 5 percent by chilling out a little while driving. Also: Since engines don’t use gasoline efficiently past a certain speed, a hypothetical driver could reduce emissions even more by never driving faster than 61 mph.

I will also say that, based on my experience growing up with a dad whose default driving speed was about 60, driving at that speed on many U.S. highways and backcountry roads is going to piss a lot of people off. They will honk, tailgate, flash their brights at you, and jokingly and not-so-jokingly pretend like they’re about to run you off the road when they do pass you. It’s a little harder to maintain zen composure under those circumstances, but that will just make those times that you do accomplish it even more impressive.

4. Fly coach

Or, well, don’t fly at all. But when taking a train from SF to NY takes four days, and flying takes about six hours, it’s not hard to see why a lot of people fly. In some cases, flying can produce less emissions than driving (if you drive alone — not if you take a train or the bus).

There’s also some information out there about which airlines are the most fuel efficient. (Spoiler: This more or less correlates precisely with which carriers pack flyers in like sardines and make them pay extra to check their bags.)

5. Fly nonstop

Planes use a disproportionate amount of fuel during takeoff, so minimizing the number of takeoffs is relatively easy (if more expensive). If you need to take a connecting flight, choose the option that gives you the least number of miles traveled.

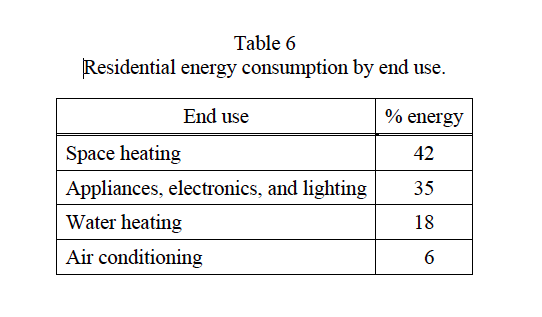

6. Turn down the thermostat

Right. And put on a sweater. While people who use air conditioning inspire all those summer energy conservation think pieces, according to Sivak and Schoettle’s stats, it’s heating the air and water around us to a temperature that we like that is the greater problem.

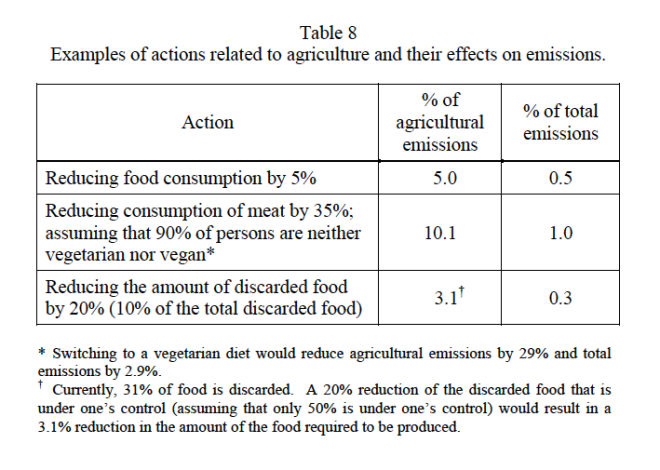

7. Eat low on the food chain

Sivak and Schoettle cite stats (published in Climatic Change in 2014) suggesting that the average vegetarian diet produces 32 percent lower emissions than the average omnivore diet. Are there ways around this? Sivak and Schoettle don’t get into this, but yeah, it gets complicated. Some processed vegetarian food has a pretty hefty carbon footprint, and if you live somewhere with an abundant white-tailed deer or squirrel population, you’ve got some low-carbon meat nearby. Still, this is about averages, not your Hunger Games lifestyle.

Sivak and Schoettle also suggest that we all try reducing our collective caloric input by 1 percent, eating 25 fewer calories a day (if we’re men) or 20 fewer a day (for women) — about a tablespoon of hummus, or a single egg white, if you even think measuring things in calories makes sense (I don’t). Their excuse? “Given that 69 percent of American adults are overweight (CDC, 2015), most of us could safely lose some weight.” Dudes. Really. The low-carbon agricultural revolution will not come any faster because you fat-shamed America.

Sivak and Schoettle also suggest that we all try reducing our collective caloric input by 1 percent, eating 25 fewer calories a day (if we’re men) or 20 fewer a day (for women) — about a tablespoon of hummus, or a single egg white, if you even think measuring things in calories makes sense (I don’t). Their excuse? “Given that 69 percent of American adults are overweight (CDC, 2015), most of us could safely lose some weight.” Dudes. Really. The low-carbon agricultural revolution will not come any faster because you fat-shamed America.

So: I have read a lot of reports like this one before. This one is particularly weird, though, because it focuses so much on personal choice, and ease of that choice. And because its definition of “ease” makes no sense.

As Sivak and Schoettle put it:

This study did not exhaustively examine all possible actions that an individual can take to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The emphasis was on selected actions that do not require substantial effort and time, do not require much in the way of changing one’s lifestyle, and are relatively easy to quantify in terms of their effects. Examples of actions not considered are increasing home insulation (takes both substantial effort and time), eliminating the use of drive-through banks and restaurants, and thus eliminating the associated idling (requires a change, albeit small, in one’s lifestyle), and buying locally sourced products (effects are not easy to generalize because they vary from product to product).

I’m not quite sure what to make of the fact that the study’s authors have somehow decided that going vegetarian, or figuring out how to consistently eat a tablespoon less of hummus than you usually do, is less arduous than parking your car, getting out of it, and going into a building to order food.

Let’s take this study at face value. What can a hypothetical person do to cut emissions easily, when they are not trying very hard to do anything? The answer to that question is, by far and away, this one: Buy a more fuel-efficient car.

But here’s the thing. The only reason we have fuel-efficient cars to buy is because of political pressure, rather than individual choice — the first Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards were created by Congress in 1975. The newest CAFE standards, which are intended to get the average mpg up to 54.5 mpg by 2025, were the result of hard bargaining — and an auto industry that had been weakened by the recession. At the time that the standards were finalized in 2005, only two cars (the Chevy Volt and a thing called a Ford Focus BEV FWD) met that standard — even the much-hyped Toyota Prius didn’t qualify. Now there are a handful that get nearly double that — but the average mpg of cars sold actually fell slightly between 2014 and 2015, probably because of lower gas prices.

Meanwhile, for way too long, the low-income people with long commutes who would have the most practical incentive to drive a fuel-efficient car have been locked out of the market for one, even as the current housing status quo pushes them farther out into the suburbs. Individual choice only goes so far: Sometimes you need the whammy of regulation to change the available options before you can get to the point where you have a choice.

On paper, it’s totally possible for the U.S. to transition to lower carbon emissions and still have a strong economy. But looking at the numbers alone leaves out the huge political and social obstacles — angry oil barons, stick-in-the-mud utilities, car companies that would rather roll out old models than develop new tech — that have to be overcome to make that happen. You can’t buy fuel-efficient vehicles until companies are under pressure to actually make them — and to make them affordable. You can’t reduce the amount of time you spend driving unless your city or suburb actually has the infrastructure (sidewalks, transit, zoning that allows jobs and housing and shopping to coexist) that makes such changes possible.

Climate change is not something that we can conserve our way out of individually or easily. As Maggie Koerth-Baker put it in her excellent book Before the Lights Go Out, if we Americans were going to conserve our collective way out of climate change, we would have to reduce our emissions to less than one ton per person. While one ton seems like a big number, “one ton of greenhouse gas emissions buys a year’s worth of heat for one average home in the United States, Pacala says. That’s not including electricity, clothes, food, or transportation. Do you travel a lot for business? Maybe you could spend your one ton of emissions on airline flights instead. On that yearly budget, you can afford to fly 10 thousand miles in coach. Of course, again, that leaves you with no food to eat, no clothes to wear, and no house to come home to.”>getting to it is much harder than it sounds:

One ton of greenhouse gas emissions buys a year’s worth of heat for one average home in the United States … That’s not including electricity, clothes, food, or transportation. Do you travel a lot for business? Maybe you could spend your one ton of emissions on airline flights instead. On that yearly budget, you can afford to fly 10 thousand miles in coach. Of course, again, that leaves you with no food to eat, no clothes to wear, and no house to come home to.

Getting to less than a ton per person — in the U.S., anyway — would involve a level of change that hasn’t been seen since WWII. Back then, tires, automobiles, typewriters, bicycles, gasoline, sugar, coffee, meat, cheese, butter, firewood, and coal were all rationed. Factories stopped making consumer products and concentrated on the war effort.

The national speed limit was set to 35 mph to conserve fuel. All forms of automobile racing were banned. Driving for “sightseeing” was banned. Special courts were set up to deal with those who broke the law — people who were found to be driving “for pleasure” had their gasoline rations taken away.

I’m not suggesting we go full WWII on climate change. (For one thing: We had more trains then. For another thing: We could get a lot done with just a Cold War approach.) What I am saying is that, yes, we can change our individual ways — and we should. But with a problem as big as climate change, we shouldn’t pretend that we can go it alone.