In March 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic brought the world to a screeching halt, some dared to wonder whether the coronavirus could have a lasting impact on climate change. Huge amounts of carbon dioxide emissions from cars, trucks, and aviation had disappeared virtually overnight. And while scientists and policymakers knew that reopening the economy would likely cause emissions to resurge, they hoped that governments’ green stimulus plans — often called “Build Back Better” plans — could mark a turning point in the world’s fight against climate change.

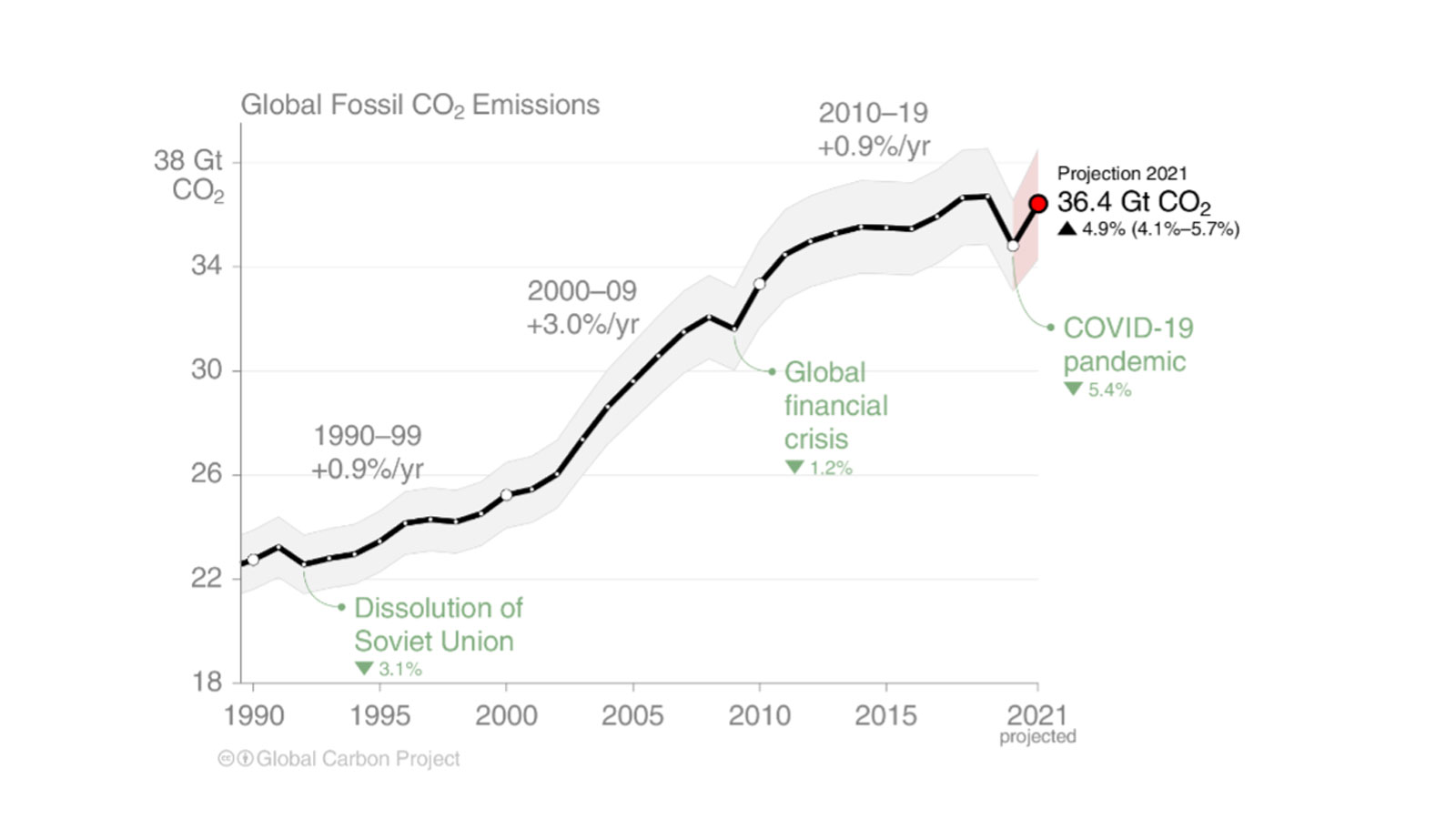

That does not appear to have happened. According to a study pre-print released this week by the Global Carbon Project, greenhouse gas emissions have rebounded this year, and will likely come close to — or even equal — the world’s emissions in 2019. (The study is currently undergoing peer review.) In 2020, emissions plummeted by 5.4 percent; this year, they are projected to increase by 4.9 percent.

“I wasn’t surprised to see a rebound,” said Rob Jackson, a professor of earth system science at Stanford University and one of the authors of the study. “I was surprised to see emissions bounce back like a rubber band.”

The main reason is coal. Coal emissions have skyrocketed, and are expected to far surpass 2019 levels, largely because of an increase in coal use in China. (China consumes more than half of the world’s dirtiest fossil fuel, and its economy recovered relatively quickly from the coronavirus pandemic.) While President Xi Jinping of China has promised that the country will zero out its carbon emissions by 2060, the government recently urged coal mines to increase production to meet rising electricity demand. India’s emissions, meanwhile, have also increased compared to 2019 levels.

The story from most other countries is more positive — emissions from the U.S. and the European Union are expected to stay below where they were in 2019. But Jackson cautions that may not be cause for celebration: Because of the coronavirus pandemic, there are still fewer cars, trucks, and planes spewing CO2 into the atmosphere in those countries than there would be in a normal year. When transport returns fully, there could be another spike in carbon pollution.

“The real issue is what happens next,” he said. “If U.S. and E.U. emissions go back to normal, it’s possible we’ll have another emissions record” in 2022.

The news from the Global Carbon Project makes for a grim contrast with what’s happening in Glasgow, Scotland, as diplomats from around the world gather for COP26, the U.N. climate summit. The meeting has been filled with talk about phasing out coal production — 40 countries, including Vietnam and Chile, recently pledged to end coal use in the 2030s — and ending financing of coal projects in other countries. But the biggest players haven’t made strong commitments. The U.S. signed onto an agreement to end international coal financing this week, and China has made a similar vow. But neither country has pledged to end coal use domestically.

And, while there are some signs of progress — according to a U.N. analysis, the world is now on track for about 2.7 degrees Celsius of warming, instead of a nearly unthinkable 4 degrees — the fact remains that as long as any CO2 is poured into the atmosphere that can’t be sucked up by the oceans and land, the planet will continue to warm. Even flat greenhouse gas emissions means higher temperatures, fiercer wildfires, and a planet increasingly thrown out of balance.

When it comes to CO2 emissions, Jackson said, “Treading water is close to drowning.”