A troupe of environmental activists descended on Rotterdam, Netherlands, last month for an evocative demonstration. Dressed as jellyfish, sea anemones, and “fisher folk,” protestors from the advocacy group Ocean Rebellion sang songs and projected messages onto the hull of a 750-foot-long drilling ship, urging policymakers to protect the seafloor from mining companies.

“The Deep Sea Says No,” some signs read, as others called seabed mining “100% Unnecessary.”

Deep-sea mining in international waters is currently illegal, and environmental organizations, scientists, and many governments want to keep it that way. They argue that the practice could irreversibly harm one of the planet’s remotest ecosystems, one of the few places on Earth that has largely escaped human disruption.

Now, their calls have become increasingly urgent, as international regulators are expected to begin issuing deep-sea mining permits by the summer of 2023. Activists are trying to enlist everyone from tech companies to United Nations delegates in an all-hands-on-deck push to stop mining companies from exploiting the seabed.

“The ocean is 70 percent of this planet,” said Clive Russell, an activist with Ocean Rebellion. “We need to stop people from abusing it.”

The case for deep-sea mining is simple: As the world transitions away from fossil fuels, increased demand for technologies like electric vehicle batteries and solar panels will require massive quantities of cobalt, manganese, nickel, and other clean-energy metals. Land-based metal reserves are few and far between, and they’re often located near communities that are harmed by mining activities. But there are billions of dollars’ worth of these metals at the bottom of the ocean — far from civilization — and no one is yet taking advantage of them.

Some also argue that, by powering clean-energy technologies and thereby accelerating a shift away from fossil fuels, deep-sea mining will protect the oceans from unabated climate change. Rising CO2 emissions have already caused devastating ocean acidification, deoxygenation, and the decline of marine species populations around the world. Gerard Barron, CEO of the Metals Company, a Canadian firm that is already preparing vessels to begin mining the ocean deep, has argued that deep-sea mineral deposits are “the easiest way to solve climate change.”

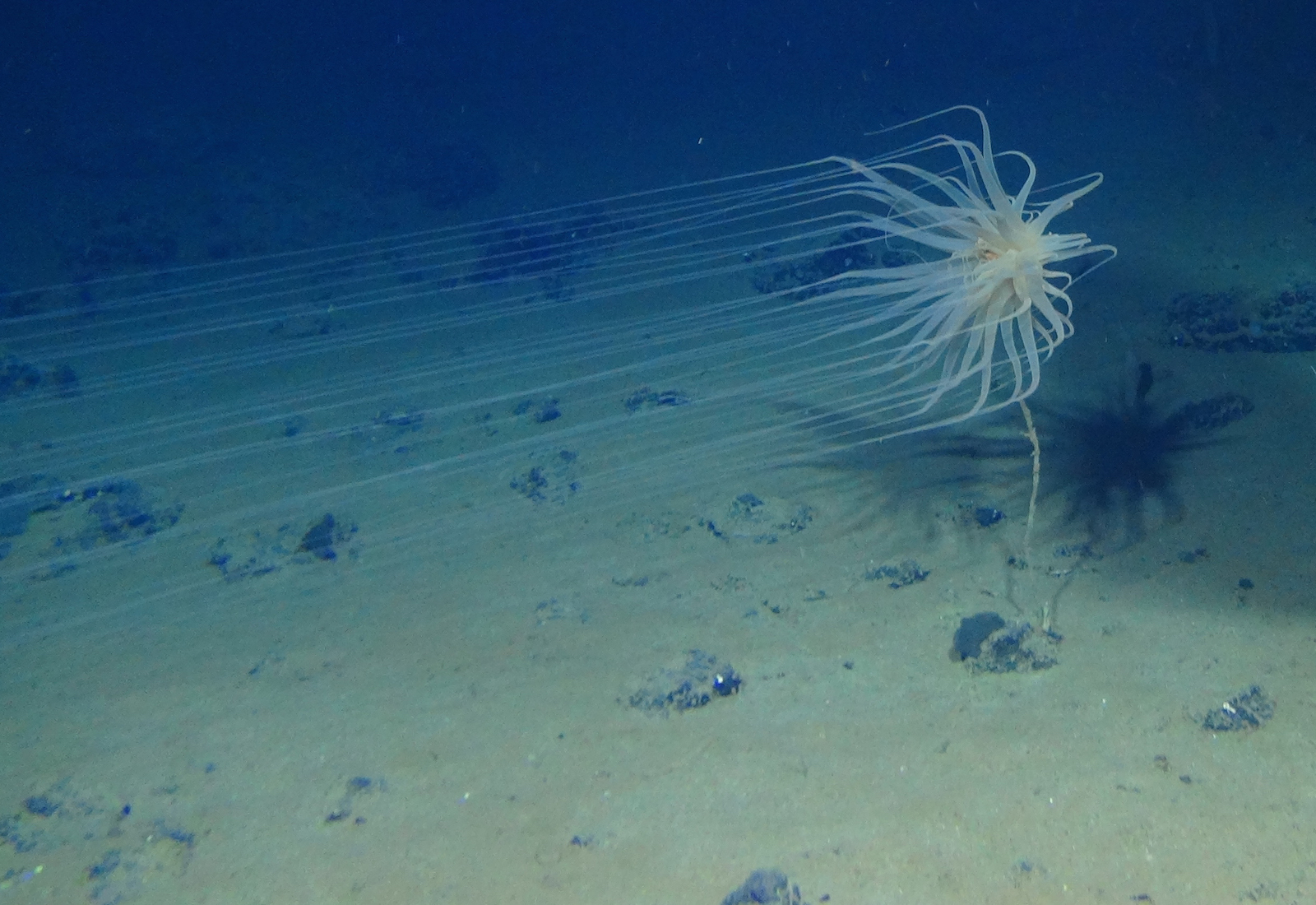

However, ocean experts vehemently disagree. The deep sea is one of the planet’s most obscure places, home to tens or even hundreds of thousands of plant and animal species that are still unknown to humans. Scientists argue it would be reckless to disrupt this environment. According to research from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, more than half of marine species in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone — a mineral-rich fracture zone that extends 4,500 miles along the floor of the Pacific Ocean — are dependent on the deep-sea mineral deposits that mining companies have set their sights on. Removing these potato-shaped deposits, which are known as polymetallic nodules, “would trigger a cascade of negative effects on the ecosystem,” the researchers concluded. And recovery would be nearly impossible, given the fact that these nodules take millions of years to develop.

There are other worries, too. Deep-sea mining would kick up debris from the ocean floor, and scientists worry that clouds of sediment could clog marine species’ filtration systems and make it harder for them to see through the water. Sonic disruptions caused by mining could also reverberate far and wide, negatively impacting whales and other species that rely on sound waves to hunt for prey. Meanwhile, fishing industry representatives have highlighted the practice’s risks to commercial fish stocks.

“The threat to biodiversity is really quite concerning,” said Jeffrey Drazen, a professor of oceanography at the University of Hawaii, Manoa. Drazen also warned that seabed mining could potentially exacerbate climate change by disrupting carbon sequestration dynamics in the deep ocean.

In short, experts agree that too little is known about the dangers of seabed mining for it to proceed safely, while a growing number assert that its risks vastly outweigh its potential benefits. The world’s clean-energy needs can be met with land-based mining, they argue, or better yet through technological innovation and dramatically improved recycling infrastructure that could significantly reduce the need for most mining in the first place.

Helen Scales, a marine biologist who teaches at the University of Cambridge’s Institute of Continuing Education, also emphasized the need for far-reaching, creative changes in the way the world adapts to climate change — like the dramatic expansion of public transportation. “Looking to the deep sea and saying we’re going to use those metals to build a billion electric cars is assuming that that’s what we should be doing,” she said. “It’s a very simplistic argument to say the only route to reduce carbon emissions is by mining the deep ocean.”

The reason the debate about deep-sea mining is escalating now is because of a surprise move from Nauru, a tiny island nation in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. Last summer, Nauru sent a letter to the International Seabed Authority, or ISA — the organization charged by the United Nations to regulate mineral-related activities in the deep ocean — expressing its intent to begin mining the seafloor in international waters. This triggered an obscure “two-year rule,” forcing the ISA to begin issuing deep-sea mining permits by the summer of 2023. The ISA will attempt to finalize regulations for seafloor mining before that deadline, but this is not necessarily required by law; ISA regulators are expected to open up the seabed to mining companies next summer even in the absence of a mining code.

It’s unclear whether the Metals Company, the firm that is partnering with Nauru, will have the technological or financial capacity to begin mining so soon. Duncan Currie, an international environmental lawyer who has worked with the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, said that disagreements between countries over profit-sharing for deep-sea metals could also delay the start of large-scale seabed mining. The U.N Convention on the Law of the Sea explicitly calls for the “equitable sharing of the financial benefits” among ISA member countries and the European Union, Currie explained, but countries are “miles apart” on what that sharing should look like. Still, the timeline imposed by the two-year rule has still frightened many scientists and environmental advocates, who fear a “race to the bottom” for seabed metals.

“It’s reckless,” said Farah Obaidullah, founder of the advocacy group Women4Oceans. “This is something we know ahead of time is going to cause irreversible damage to the deep seas,” and it could begin without rules or regulations in place.

The Metals Company did not respond to Grist’s request for comment for this story.

Environmental advocates’ ultimate goal is to convince international lawmakers to put in place a moratorium on deep-sea mining. In response to the ISA’s looming deadline, 622 marine science and policy experts have called for a pause on the practice. Eighty-one governments and government agencies in the International Union for Conservation of Nature similarly called for a ban last fall. Other organizations and prominent individuals — including nature broadcaster David Attenborough and oceanographer Sylvia Earle — have made similar, often impassioned, pleas that seabed mining be halted.

Because the ISA has mining industry ties, experts don’t expect the group to ban deep-sea mining. The only body with the power to supersede the ISA’s authority and implement a moratorium on deep-sea mining is the U.N. General Assembly — but advocates don’t expect that to happen anytime soon. It’s very possible that companies could begin drilling in the deep ocean before U.N. member countries have a chance to stop them.

Given the pressing timeline, many advocates have focused on strategies that could offer immediate, albeit limited, protections for the deep sea while simultaneously drumming up support for a moratorium.

One strategy is to get large, metal-hungry companies to publicly disavow seabed mining. Arlo Hemphill, a senior oceans campaigner for Greenpeace, said these disavowals could show mining interests that there is insufficient demand from large corporations to make seabed mining profitable. The tactic has gained some traction, with large tech and car companies like Google, BMW, and Samsung promising to keep deep-sea metals out of their products. Banks like Triodos have also promised to exclude deep-sea mining from their financing.

Another approach would be U.N. intervention to bar deep-sea mining in critical ocean areas like the Clarion-Clipperton Zone. This is what some advocates hope could happen at a U.N. conference on marine biodiversity in international waters that will take place in New York starting this week. The conference is focused on the high seas, but according to Hemphill, it’s possible that it could have implications for the deep ocean as well. If negotiators agree on a treaty creating sanctuary zones for marine species — whales, for example — it could place entire swathes of the ocean out of the reach of mining companies.

The catch, however, is that for this approach to be effective, sanctuary zones would have to extend all the way down the water column, from the surface to the ocean floor. This is a big hurdle; according to Obaidullah, much ocean policy fails to connect these two sections of the ocean, treating them as distinct realms.

“As somebody with common sense, I don’t see how that’s possible,” she said. “If you start mining the deep ocean, you’re going to have sediment plumes in the water column at all stages, at all depths.”

Another caveat: Even if the U.N. comes up with a powerful treaty at its March meeting in New York, Obaidullah noted that ratification and implementation could take years — much longer than the 16 months remaining before mining companies may begin breaking ground in the deep ocean. She envisioned a scenario in which the ISA is opening up vast tracts of the seabed to extraction, even as other bodies are still haggling over how to conserve the waters directly above.

Hemphill expressed hope that a growing spotlight on the Metals Company, the two-year rule, and the dangers of deep-sea mining will stop the practice in its tracks. He supports a moratorium, but stressed the need to pursue parallel objectives: working to reduce or dependency on clean energy metals, for instance, by boosting recycling, designing products to last longer, and investing in public transit systems as an alternative to electric cars.

Russell, the Ocean Rebellion activist, agreed, calling for a sea change in the way humans interact with the ocean. “We need to begin to question why these people think that it’s a good idea to go deep-sea mining in the first place,” he said. “We have to start changing our relationships to the planet, and a big part of that is the ocean.”