It’s hard to remember, It�

An international team of experts drew on decades of work on climate and health in order to demonstrate that rising temperatures and other consequences of burning fossil fuels are inextricably linked to every facet of human health. They looked at 43 indicators, things like heat, infectious disease, and drought, to track the health effects of the changing climate.

Lancet has produced an updated version of this report, called the “Lancet Countdown: Tracking Progress on Health and Climate Change,” every year since 2015. (The previous years it has published have coincidentally been the five hottest on record.) But this year’s report, the authors said, is “the most worrying outlook” they’ve ever published. The Lancet not only took a host of new climate-health risks into account, it also found that “a concerning number of indicators are showing an early, but sustained, reversal of previously positive trends identified in past reports.”

So, are we totally doomed? Let’s take a look at the biggest takeaways.

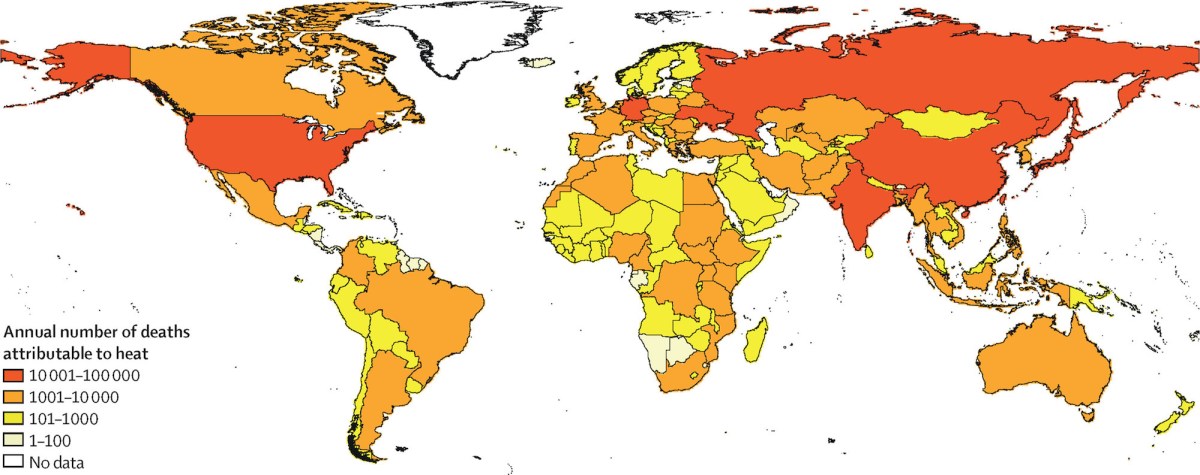

Heat-related mortality is on the rise

Reprinted from The Lancet, Watts et al, The 2020 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: responding to converging crises], Copyright (2020), with permission from Elsevier The Lancet

The researchers found that extreme heat led to nearly 300,000 deaths of people over 65 in 2018, representing a 54 percent increase over two decades. Heat led to nearly 19,000 additional deaths in the U.S.

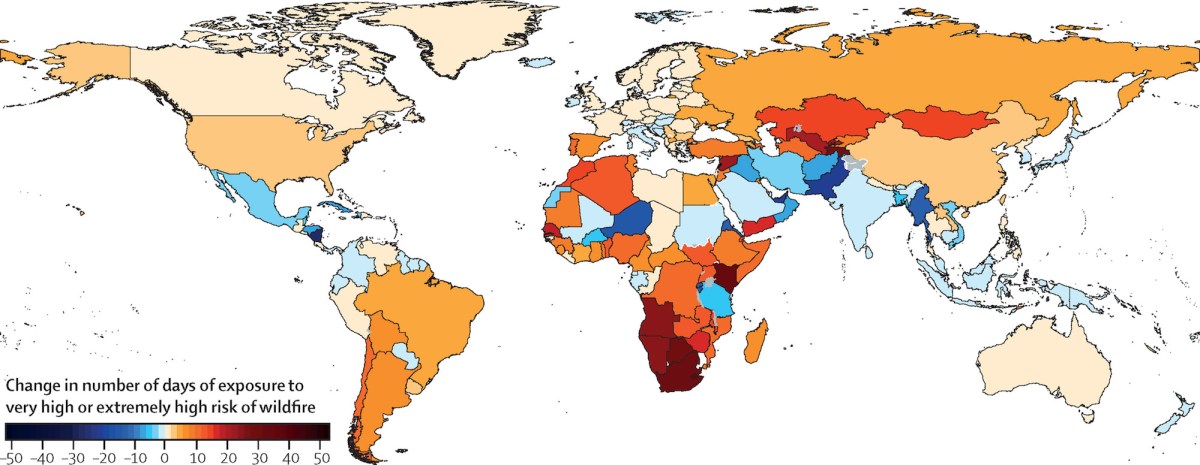

Wildfires are affecting larger areas of land and larger quantities of people

Reprinted from The Lancet, Watts et al, The 2020 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: responding to converging crises], Copyright (2020), with permission from Elsevier The Lancet

The researchers looked at daily wildfire risk in 196 countries from 2016 to 2019 and compared it to the period between 2001 and 2004. They found that 114 of those countries experienced higher wildfire risk in the second decade of the 2000s — and some 194,000 more people per year are exposed to wildfires around the globe.

Climate change increases the transmission of some infectious diseases

The climate is becoming less compatible with human life, but more suitable for the transmission of infectious diseases like dengue, malaria, and Vibrio, a harmful bacteria that lives in some coastal waters. The global transmission potential of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, two types of mosquitos that carry dengue fever, have increased 9 percent and 15 percent, respectively, since the 1950s. While conditions for malaria and Vibrio aren’t improving across the board, certain regions are becoming much more friendly to those two diseases. In the Western Pacific (the region that stretches from Mongolia down to New Zealand), for example, the conditions that allow malaria to spread increased 150 percent. In the Atlantic Northeast coast of the U.S., the coastline became 99 percent more suitable for the transmission of Vibrio bacteria.

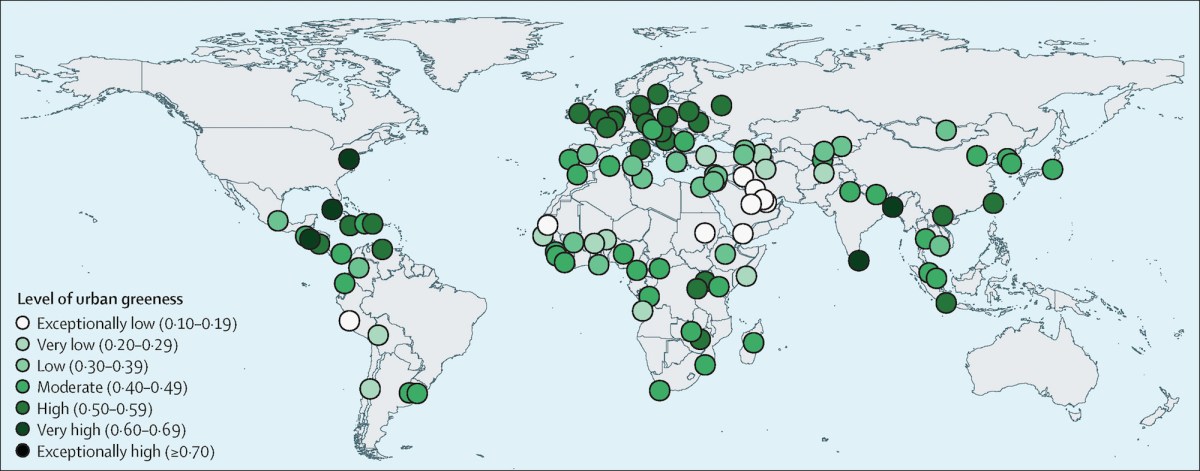

Many city dwellers don’t have access to green space

Reprinted from The Lancet, Watts et al, The 2020 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: responding to converging crises], Copyright (2020), with permission from Elsevier The Lancet

Urban green spaces reduce exposure to air and noise pollution and heat, and they’re generally good for bringing down stress levels and reducing all-cause mortality. But only 9 percent of global urban centers had a “very high or exceptionally high degree of greenness in 2019,” according to the report. More than 156 million are living in cities with “concerningly low levels” of green space.

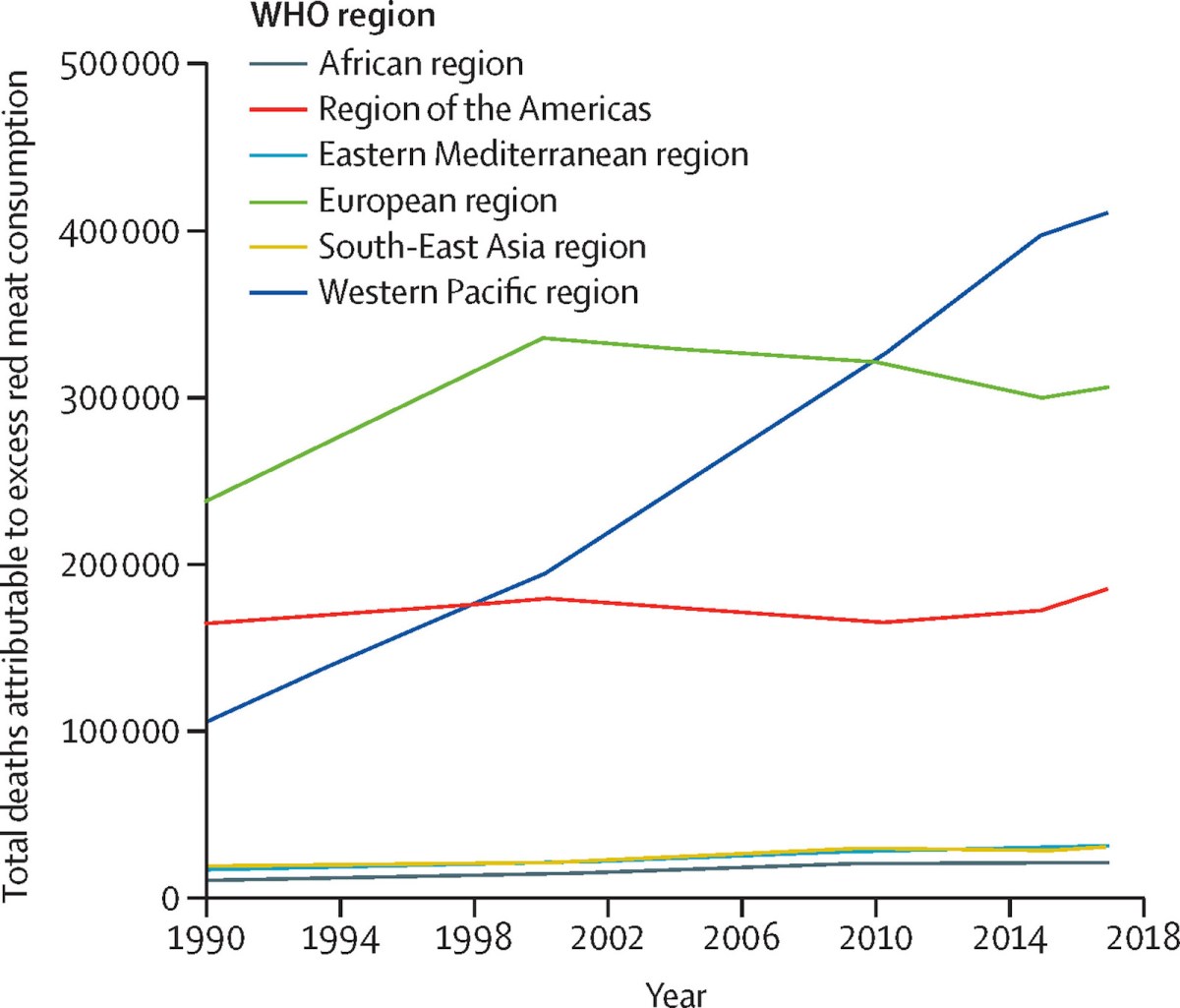

Red meat consumption is bad for the planet … and us

Reprinted from The Lancet, Watts et al, The 2020 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: responding to converging crises], Copyright (2020), with permission from Elsevier The Lancet

The ruminants we raise to eat — cows, sheep, and other herbivores in possession of a specialized stomach for fermenting plants — are responsible for 93 percent of total livestock emissions. In the long term, red meat is a serious contributor to climate change. In the short term, it’s a serious contributor to death. The report found a 72 percent increase in the global number of deaths due to red meat consumption between 1990 and 2017. High red meat consumption was responsible for nearly a million deaths in 2017.

Before you find a sand dune to bury your head in, take heart: The report demonstrates that addressing the climate crisis often saves two birds with one, err, strategy. Slashing emissions slows runaway warming and prevents excess heat-related mortality. Reducing red meat consumption can help countries preserve the health of their citizens and align their emissions with the targets laid out in the Paris Agreement. Investing in more urban green spaces fosters equity, improves health outcomes, and increases the number of trees sucking carbon out of the air. You get the picture.

The outlook includes some plainly positive trends, too. In 2019, 77 percent of global cities surveyed by the Lancet had developed climate change risk assessments. The use of electricity for road transport — for things like electric cars and buses —rose 18 percent in just one year between 2016 and 2017. The following year, the global electric vehicle fleet increased by a whopping 64.5 percent. And from 2018 to 2019, the proportion of newspaper articles on climate change and public health in 36 countries increased 96 percent.

Perhaps most importantly, the report notes that the COVID-19 pandemic, as devastating as it has been, has created the conditions for a rare moment of global reckoning. “2020 will probably be an inflection point,” the report says, “with the direction of future trends yet to be seen.” No time like the present to do our darndest to avert planetary collapse and preserve the well-being of our species!