In a pair of little-noticed letters sent earlier this year, Ohio Senator Sherrod Brown and five other Democratic senators asked two giant organizations crucial to keeping the country’s housing market running how they were preparing for the destructive power of climate change. “If we are underprepared, climate change could have particularly devastating impacts on the individuals and communities who can least afford it,” the letter warned Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government-supported companies that back roughly half of the country’s $10 trillion mortgage market.

The financial world and those responsible for regulating it have been waking up to the threat posed by global warming. Earlier this year, the head of the world’s largest investment firm, BlackRock, said that climate change is causing a “fundamental reshaping of finance.”

And as investors, bankers, and others in finance accept that they must rethink how they operate, some insurance companies and lenders are responding by reducing their risks to flooding, wildfires, and other natural disasters. It’s a shift likely to put a bigger burden on state and federal governments and — ultimately — taxpayers when disaster hits.

Floodwater surrounds homes in the aftermath of Hurricane Irma in Callahan, Florida, in September 2017. Grist / Jabin Botsford / The Washington Post via Getty Images

As losses from hurricanes, wildfires, and other natural disasters balloon, insurance companies have retreated from risky areas, leaving homeowners in large swaths of Florida, Texas, and California to rely on subsidized state programs, which are struggling to stay financially sustainable.

At the same time, mortgage lenders making loans to homebuyers in some high-risk areas are increasingly selling those riskier loans to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which pool the country’s mortgages into financial assets. If government-backed insurance programs and mortgages fail, it could result in demand for billions of dollars of taxpayer money for bailouts.

“It’s not that the risk has been mitigated,” said Lauren Compere, a managing director and director of shareowner engagement at Boston Common Asset Management, an investment management firm specializing in socially responsible investing. “The risk doesn’t go away. They’ve just shifted it to another actor in the financial system.”

Experts say if these climate risks are left unaddressed, the combined effects could ripple across the economy in ways that mirror the subprime mortgage crisis of 2007 — this time fueled by climate change.

It’s a scenario that could play out soon. A working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research this week found that homes at risk of flooding in the U.S. are currently overvalued by $34 billion, pointing to a potential real estate bubble thanks to climate threats. Recent research by the consulting firm McKinsey likewise concluded that coastal homes in Florida could lose 15 to 35 percent of their value by 2050. In Miami-Dade County, a separate analysis by Jupiter Intelligence, a firm that models climate risk, found that the loss of mortgage value could increase by 25 percent by 2050. A McKinsey analyst told The Financial Times that the Jupiter analysis indicated that loss rates from mortgage defaults could skyrocket to levels seen during the 2007 financial crash within the next 20 years.

“With 4 degrees [temperature increase], if not well before, you’re at an uninsurable world,” said Sue Reid, vice president of climate and energy at Ceres, a nonprofit advocating for sustainable practices in the business world. “Ongoing, business-as-usual practice is propelling us to an unbankable world.”

Risky pools

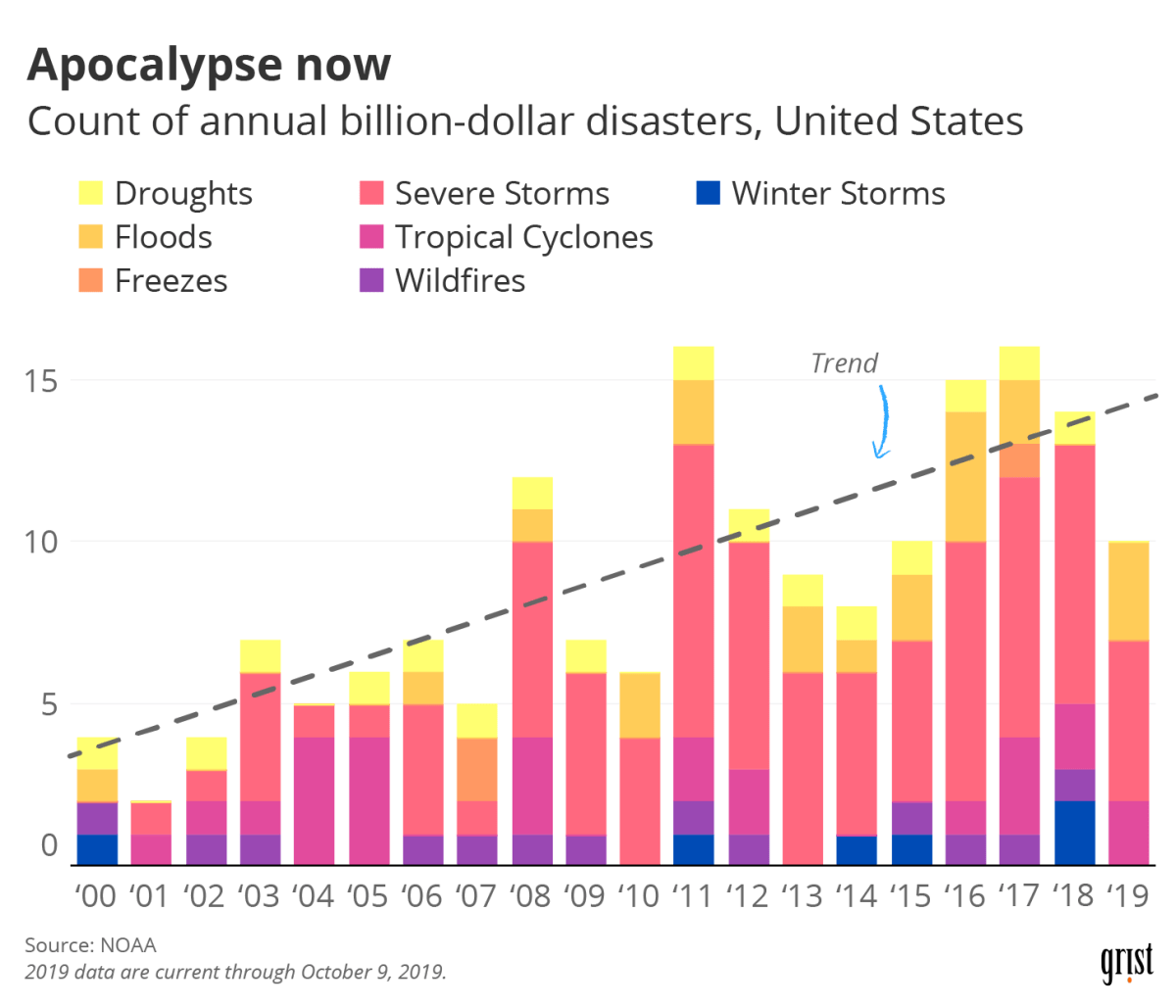

These concerns aren’t new. The insurance industry studied the potential effects of climate change–related risks as early as the 1970s. But it wasn’t until 2005, when insurers suffered record losses from hurricanes Rita, Wilson, and Katrina, that the issue started looking like a serious threat to their business. That year, insurers paid out roughly $60 billion in claims, largely as a result of the three hurricanes. It was a turning point for the industry.

An insurance policy number is spray-painted on the remains of a home that was destroyed by Hurricane Katrina in September 2005. Grist / Spencer Platt / Getty Images

Insurance payouts have reached new heights since then, with each year bringing an onslaught of hurricanes, floods, and wildfires. In the last decade, payouts tied to natural disasters averaged $31 billion a year, compared to $19 billion the previous decade. Insurers paid $105 billion in disaster-related claims in 2017 when hurricanes Harvey, Maria, and Irma battered the Texas, Puerto Rico, and Florida coasts.

The costs have already pushed some insurance companies to financial ruin. After Hurricane Katrina, Poe Financial, the fourth-largest insurer in Florida, declared bankruptcy, and after the Camp Fire flattened towns in northern California, Merced Property and Casualty Company was liquidated to pay out insurance claims.

The rising risks have led insurance companies to rethink their policies, both in terms of where they offer coverage and for how much. In many coastal and wildfire-prone regions, insurers are retreating, finding that the potential losses just aren’t worth the business. In cases where the industry is willing to offer policies, premiums are rising. California homeowners living in areas at high risk for wildfires, for example, have seen their premiums rise by as much as 500 percent.

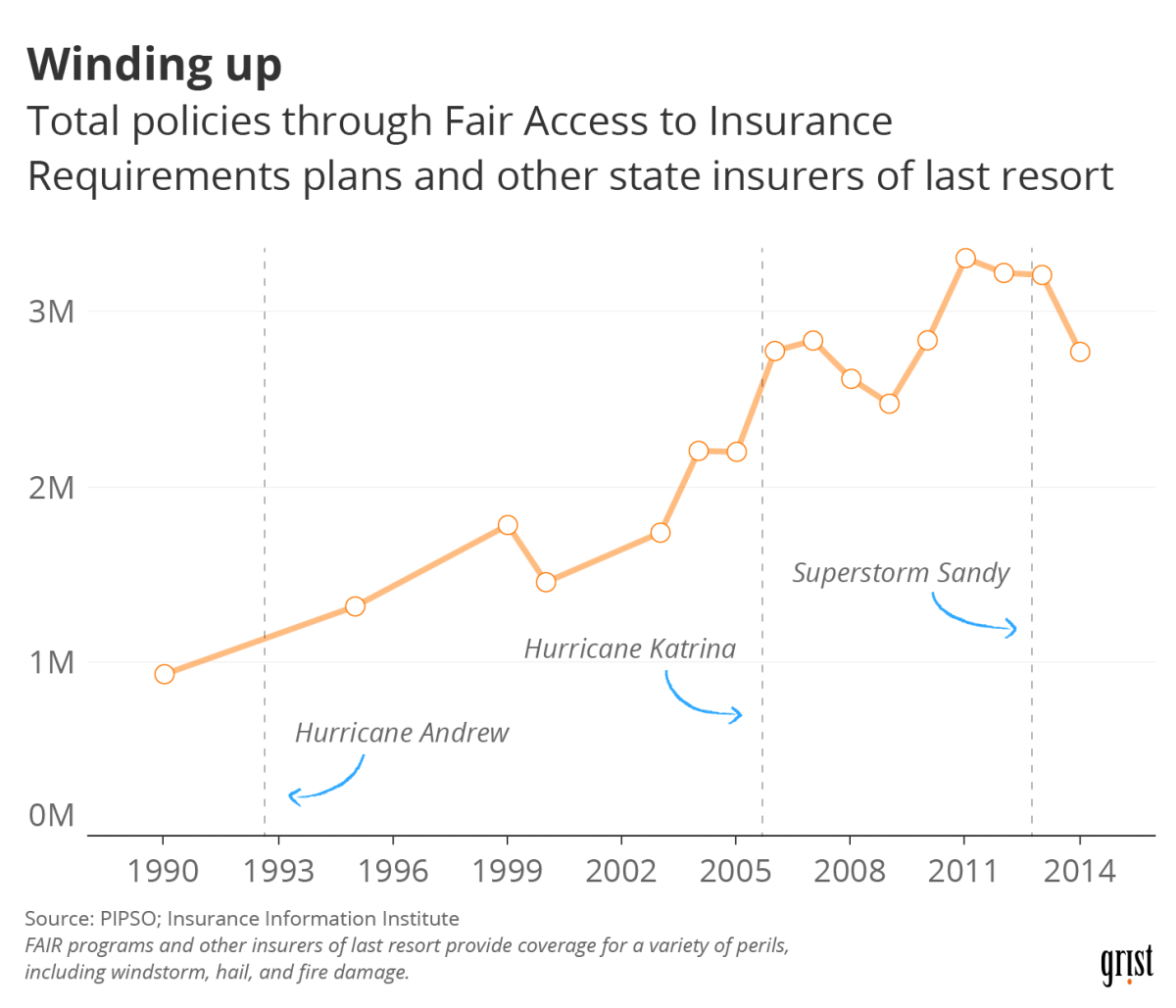

As a result, homeowners who need fire, windstorm, and hail insurance are increasingly turning to subsidized, state-backed programs. Typically called FAIR — or Fair Access to Insurance Requirements plans — about 30 states have an insurance program of last resort for homeowners unable to find insurance on the private market. These programs have ballooned in recent decades. In 1990, FAIR programs held about 780,000 insurance policies. By 2014, that figure had grown to about 2.1 million.

Grist / Clayton Aldern

A 2016 report by the Insurance Information Institute said that “many state-run residual property insurers have morphed from markets of last resort to become major insurance providers in their states.” The report noted that demand for these programs remained high because most of them offered cheaper, subsidized rates, with private reinsurance money and government funding covering the growing gap between revenue from premiums and losses from payouts.

The Texas Windstorm Insurance Association, for example, is the insurer of last resort for 14 coastal Texas counties, providing windstorm insurance to people who can’t find it on the private market. The program has grown from about 50,000 policies in the 1970s and 1980s to about 250,000 in the last decade. A 2018 report from a state auditing agency concluded that after Hurricane Harvey, the program is “broke, in debt, and facing a shrinking revenue pool.”

A similar trend is afoot in California. In the 10 counties with the highest risk of wildfires, the number of FAIR policies jumped 177 percent between 2015 and 2018. In an attempt to provide more stability to homeowners in the wake of wildfires (and stem the growth of publicly subsidized insurance in the process), the state insurance commissioner recently banned insurance companies from refusing to renew policies in wildfire-prone areas for a year.

Shifting risks related to climate change onto FAIR programs does not bode well for taxpayers. For an insurance program to work, you need a diverse mix: Premium payments from low-risk policies can support the claims arising from higher-risk policies. Too many high-risks in a pool raises the odds that the program is unable to pay out claims when the next disaster hits. When that happens, taxpayers wind up with the bill.

In Texas, messy political fights have been brewing as to whether inland residents are willing to bear the cost of rebuilding in natural disaster-prone regions along the Gulf Coast. In 2018, the Texas governor put a freeze on the state’s windstorm insurance program rates after vocal opposition from coastal residents and representatives, led primarily by State Representative Todd Hunter from Corpus Christi.

In an impassioned speech on the Texas House floor, Hunter said he was tired of “coast bashing” and that rushing to raise windstorm premiums was equivalent to telling coastal residents, “Oh, we love you coast, but we want you to dry up.”

When disaster strikes

Changes in the insurance industry can have a domino effect on the entire economy.

For one, the cost and availability of insurance determine whether a prospective buyer can get and keep a mortgage. Lenders require homebuyers to secure homeowners insurance to qualify for a mortgage, but as insurance companies increasingly decline to provide policies in wildfire-prone areas, it can put their financing at risk.

Lenders also require separate flood insurance for certain properties, but they rely on outdated flood maps to enforce that requirement. As a result, tens of millions of people live in areas that are not considered at risk of flooding on paper — even though rising temperatures likely put them in harm’s way — and don’t have insurance. For example, according to CoreLogic, a data analytics company, about 75 percent of homes hit by Hurricane Harvey did not have flood insurance.

When a natural disaster hits, those without flood insurance and those paying higher premiums are more likely to default on their mortgage payments. This is partially because businesses close to rebuild in the aftermath of a natural disaster, putting their employees out of work. As a result, homeowners may face a loss in income while also having to shoulder the cost of rebuilding their own homes.

A woman paints the bedroom of her fire-damaged home, which survived the 2019 Camp Fire, in Paradise, California. Grist / Paul Kitagaki Jr. / Sacramento Bee / Tribune News Service via Getty Images

“It’s this double whammy that causes defaults,” said Amine Ouazad, an economics professor at HEC Montréal. “The household still has to pay property tax, and they still have to pay flood insurance on the house that they couldn’t inhabit.”

Last year, Ouazad and Matthew Kahn, a professor at Johns Hopkins University, published a working paper on lenders’ response to higher mortgage default risks in U.S. coastal areas hit by hurricanes causing more than $1 billion in damage. They found that lenders issued fewer loans in flood-prone areas — except in cases where they were able to sell off these loans to the government-backed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. (Fannie and Freddie were created by Congress to help improve access to housing by supporting mortgage-lending to lower- and middle-income homebuyers.)

Ouazad and Kahn examined loans above and below the so-called conforming loan limit, a threshold set by the Federal Housing Finance Authority that dictates which mortgages Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac can purchase. At the moment, Fannie and Freddie can’t buy a loan worth more than $510,400.

The two researchers found that, after a major hurricane, lenders sold fewer loans above the conforming loan limit in areas with high flood risk. But they kept selling loans below the limit and handed a larger share to Fannie and Freddie. This “bunching” of loans just below the limit suggests that lenders were “extremely conscious” of the risks, Ouazad said.

“Lenders are transferring flood risk to entities that are essentially backed by the U.S. taxpayer, which should be concerning,” he said.

Grist / Clayton Aldern

There’s some evidence to suggest lenders are modifying their behavior in response to other climate risks, too. A 2019 study found that counties where average temperatures increased by 1 degree Fahrenheit over a 36-month period saw mortgage approval rates drop by 0.9 percent. While that figure may sound small, it translated to a $13.1 million decrease in mortgage loans made in a median county each year.

Some investment firms are beginning to respond to these risks and factor them into where and how they invest. Breckinridge Capital Advisors, a Boston-based firm managing more than $40 billion in assets, has begun analyzing the risk of natural disasters on mortgage pools and factoring it into their decision-making over the past year. According to Jeffrey Glenn, the firm’s senior vice president and co-head of portfolio management, the investment team at Breckinridge has developed weighted scores for each state depending on its vulnerability to climate risks such as hurricanes, droughts, and wildfires.

“We’re using that internally to adjust the valuation of where we’d be willing to buy a particular mortgage pool,” said Glenn. “We’re making a decent additional adjustment for climate risk.”

Breckinridge appears to be in the minority. Most investment firms are not designing their portfolios to account for climate risks. In fact, according to a survey of financial institutions by researchers at the University of Texas in Austin, 97 percent of the executives contacted believe climate change is occurring — but just 24 percent consider it when making new investments.

Faulty flood maps, Fannie, and Freddie

Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Housing Finance Authority, which oversees Fannie and Freddie, have acknowledged the risks that climate change poses to the mortgage and insurance industry. In financial statements, Fannie Mae has disclosed that “a major natural or environmental disaster” could cause losses and that the “severity and frequency of major disruptive events in certain geographic areas may also be impacted by climate change.” And in 2016, a Freddie Mac report cited a study stating that coastal real estate worth as much as $160 billion is likely to be underwater (literally this time) by 2050.

The report concluded that “some of the varied impacts of climate change — rising sea levels, changing rainfall and flooding patterns, increasing temperatures — may not be insurable” and that “important features of housing finance may have to change.”

Floodwaters inundate a newly constructed house for sale in Saco, Maine, in March 2018. Grist / Gregory Rec / Portland Portland Press Herald via Getty Images

Spokespeople for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac did not respond directly to detailed questions about the companies’ analyses of climate risks in their portfolios. The companies also missed the February 21 deadline to respond to the senators’ questions about their consideration of climate risks.

But housing and economics experts say Fannie and Freddie have been slow to address climate threats. Both companies assess risks posed by natural disasters as part of their analysis of the mortgage pools that they assemble, but it is unclear if they factor climate change into their pooling practices. The companies rely on outdated FEMA maps when determining whether flood insurance requirements have been met. These maps are based on historical flood data and have been widely criticized for failing to provide an accurate picture of future flood risks.

During a House Financial Services Committee hearing last year, Mark Calabria, head of the federal housing authority, called Ouazad and Kahn’s study on lenders passing on riskier loans in flood-prone areas to Fannie and Freddie “largely correct.” He laid the blame on the two companies, which he said were carrying more debt than financially sustainable, making them especially susceptible to financial shocks after natural disasters, and the National Flood Insurance Program, which provides subsidized flood insurance to homeowners. Critics say it incentivizes people to live in risky, flood-prone regions, and in 2018, Congress wrote off $16 billion of the program’s debt after it struggled to pay out claims from hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria.

“I am concerned that if we don’t have a functioning, sustainable National Flood Insurance Program, much of that risk will get sent to Fannie and Freddie,” Calabria said. “This is something we’ve started to look at. We’re very concerned about the impact of natural disasters on Fannie and Freddie’s risk profile.”