This essay was first published in our semi-weekly newsletter, Climate in the Time of Coronavirus, which you can subscribe to here.

When lockdown hit, I found myself suddenly with more free time than I’d had since childhood. To fill it, I started to take walks. As soon as the weather finally became warm enough to tolerate the outdoors in Minneapolis, I would leave my parent’s house for three, sometimes four hours without my phone or wallet, walking the same route past landmarks from my childhood: through the parking lot behind my high school, across the highway overpass, past a park where I used to loiter with childhood friends. Finally, I would arrive at a small nature preserve where, sandwiched between the highway and the suburban sprawl, patches of tallgrass prairie and wetland are being restored.

Access to any slice of the outdoors, no matter how small, is a privilege at any time, but felt especially precious under quarantine. Free of the usual distractions, I got the chance to really pay attention to the living things we share this land with.

Like most city dwellers, I’ve always suffered from some level of species blindness — to me, birds have always just looked like birds, and plants have always just looked like plants. I had never bothered to learn their names. But, over time, these long and meandering walks gave me a new sense of place — natural landmarks to accompany my social ones. Slowly, the prairies and wetlands, and all their patterns and languages, brought a new kind of comfort in their familiarity. There’s the beaver dam near the entrance of the preserve; nearby, I can usually spot a couple of painted turtles sunning themselves on the rocks. Further along the path, red-winged blackbirds perch territorially on switchgrass and sorghastrum. Honeybees and monarchs visit milkweed and thistle. Invisible, the chorus frogs call their daily rhythms from the marshy ponds.

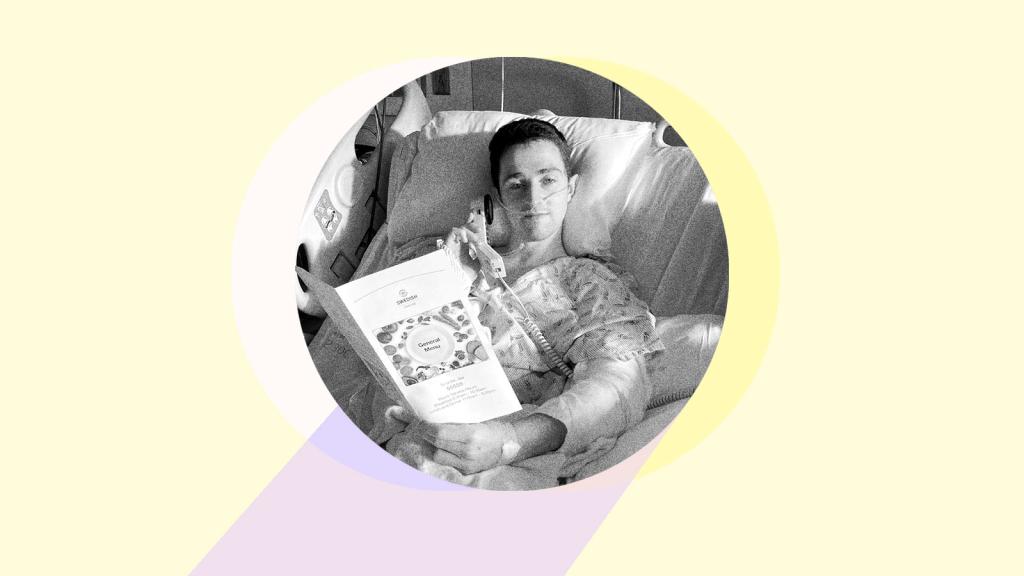

Alexandria Herr

It’s tempting to interpret this time in nature as a silver lining, but the truth is there’s no silver lining to be found in this pandemic. We are surrounded by preventable suffering that is hitting the most vulnerable among us the hardest, widening the injustices of an already unjust country. Day after day, in Minneapolis and beyond, we are witnessing the neglect of a government that does not care about the lives of its people, of police departments that brutalize communities of color and protestors, of an economic system that sacrifices workers at the altar of consumption.

What are we to make of this? I have no clue, but often I find myself returning to the words of Ross Gay, a poet who wrote a book of essays about a thing that delighted him every day for a year. To Gay, joy is not a privilege, but a muscle. “Joy has nothing to do with ease,” he said in a 2019 interview. “It is not at all puzzling to me that joy is possible in the midst of difficulty.” In other words, it is precisely because times are hard that joy is necessary. Joy sustains us, allows us to continue to care for one another and work for a better world, even when the unrelenting cruelty of the news resists reason and language.

Since March, I’ve left my parents’ house. I’ve found myself without as much time for long walks. But I’m grateful every day for the little patches of nature near my new apartment, the music of the sedge wren and the percussive woodpecker.

To me, they sound like joy.

Alexandria Herr is an intern at Grist. To see more examples of her original art, follow her on Instagram here.