For centuries, fossil fuels have been associated with prosperity, progress, and growth. But more and more economists say that the continued use of coal, oil, and gas is now driving the world in the opposite direction — toward a lower standard of living and a global economic slump.

A new report from the consulting firm Deloitte, released during the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, on Monday, found that if the world stayed on its current course, it would cost $178 trillion over the next 50 years. For perspective, roughly $500 trillion of wealth exists on Earth today. On the other hand, swift action to zero out global greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 could add $43 trillion to the global economy over the same period and, according to the analysis, plant the seeds for a green Industrial Revolution.

“Economics is on the side of a low-emissions future,” Punit Renjen, CEO of Deloitte Global, wrote in the report’s introduction, declaring that a coordinated, worldwide investment in climate action would “pay handsome dividends for the global economy.”

Deloitte’s report says that if the world warmed by 3 degrees Celsius (5.4 Fahrenheit) compared to pre-industrial times, it would hinder economic growth in every region. Economic opportunities would dwindle, since countries would have to spend money on repairing damages from climate change instead of on new innovations, and much of the world’s population would live a worse life.

“Translated into human terms, job opportunities would dry up,” the report says. “Crops would fail. Health care spending would rise.”

Economic models can sometimes be narrow in scope, but the researchers at Deloitte attempted to provide a fuller picture of the damages that global warming will inflict. They accounted for changing weather patterns, sea-level rise, and the spread of disease, calculating the toll on the labor force’s productivity, urban and agricultural land, infrastructure, people’s health, crop yields, and tourism.

“That’s what we factor now into the baseline,” said Pradeep Philip, a partner at the Deloitte Economics Institute in Australia and one of the paper’s authors. “Most economic analysis assumes that economies will grow on-trend, and that’s because they don’t take into account these factors.”

Deloitte’s report reflects a growing awareness that economic estimates have been providing a skewed view of the cost of protecting the climate. Starting in the early 1990s, oil companies and other high-emitting corporations looking to avoid regulation began paying economists to produce studies that looked solely at the costs of climate policies, making them appear prohibitively expensive to policymakers and the public. These models usually ignored the real-world costs that come with a hotter planet as well as the benefits of cutting emissions, like better air quality and healthier people.

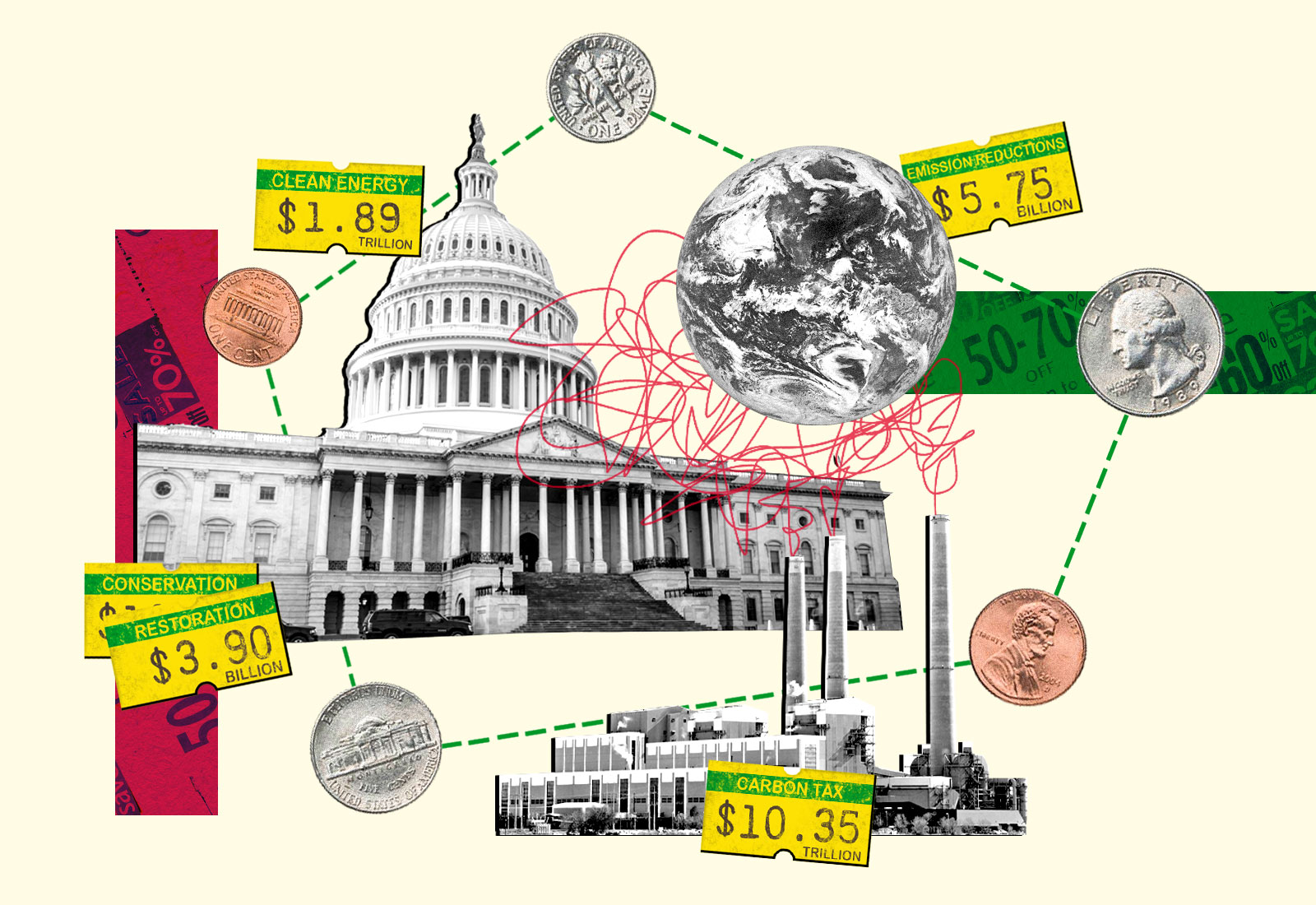

“If the economic impacts of a changing climate are left out of economic baselines, the result is likely to be poor decision-making, ineffective risk management, and dangerously inadequate efforts to address the climate crisis,” the report’s authors write. Yet this narrow economic analysis is still the dominant frame for politicians. Consider President Joe Biden’s dying climate and social policy agenda, which Democratic Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia has said he can’t support because of the sticker price — $1.7 trillion over 10 years. The policies are key to meeting Biden’s goal of cutting U.S. emissions in half by 2030, compared to 2005 levels.

The new report helps “bust the myth that staying still, or accepting the status quo, somehow had no cost attached to it economically,” said Claire Ibrahim, a partner at Deloitte Access Economics and an author of the report.

Countries in the Asia Pacific region, including China, Japan, India, Australia, and places in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands, would see the worst losses with unchecked climate change: $96 trillion by 2070. By that year, the region’s GDP would be $16 trillion lower than in an undamaged world — roughly equivalent to the current value of the entire Chinese economy, the world’s second-largest.

Europe will likely be better off, according to the modeling, but its economy would still lose $10 trillion and 110 million jobs over the same time period. By 2070, the United States would suffer $14.5 trillion in economic losses, and GDP would be $1.5 trillion lower.

If countries quickly shift away from fossil fuels and limit warming to just above 1.5 degrees C, however, modeling shows “the equivalent of an Industrial Revolution occurring in 30 years,” Ibrahim said — a huge boost to the global economy.

Although people often talk about jobs and industries vanishing if the world shifted to a low-carbon economy, Ibrahim said, they won’t simply disappear. “They transform into something else in line with what is more productive, what is more competitive, what makes sense as part of global trade,” she said. “It is a more modern economy. There are higher-paying jobs.”

There’s some appetite for that transformation. According to a survey by Deloitte last fall, 89 percent of C-level executives around the world agree that there is a “global climate emergency,” and 79 percent believe the world is at a tipping point for responding to it.

While the initial switch to a carbon-free energy system would temporarily lower economic activity, thanks to the combination of upfront investments and the already locked-in damages of climate change, the benefits would come to outweigh the costs for every region on Earth, adding new sources of growth and job creation. Deloitte expects this turning point, where the benefits of taking action exceed the costs, to come the earliest for the Asia Pacific region — during our current decade, the 2020s. On the other end of the spectrum, it may come as late as the 2050s for Europe and 2048 for the United States. That’s because these regions have more emissions-intensive structures to replace and aren’t seeing as severe consequences from climate change as some parts of the world.

Philip said he hopes that the report can help leaders see that everybody benefits by taking coordinated steps to reduce emissions, breaking through some of the deadlock in global climate discussions. “Because now, those who said, ‘You can’t make us bear the costs’” — like China and India — “can see they can gain the most,’” he said. And the rich countries that have previously benefited from fossil fuels can see that taking action is also less costly for them in the long run.

“We have squandered the chance to decarbonize at our leisure,” the report says. “Given the costs associated with each tenth of a degree of temperature increase, every month of delay brings greater risk and forestalls the eventual economic gains.”