Until recently, it looked like the best chance of climate action from the Biden administration was going to be an infrastructure bill making its way through Congress. Now, the possibility of getting strong climate provisions into that bill, like a clean electricity standard, is looking increasingly slim. But the Biden administration is pressing ahead with other tools in its toolbox to expand renewable energy in the U.S.

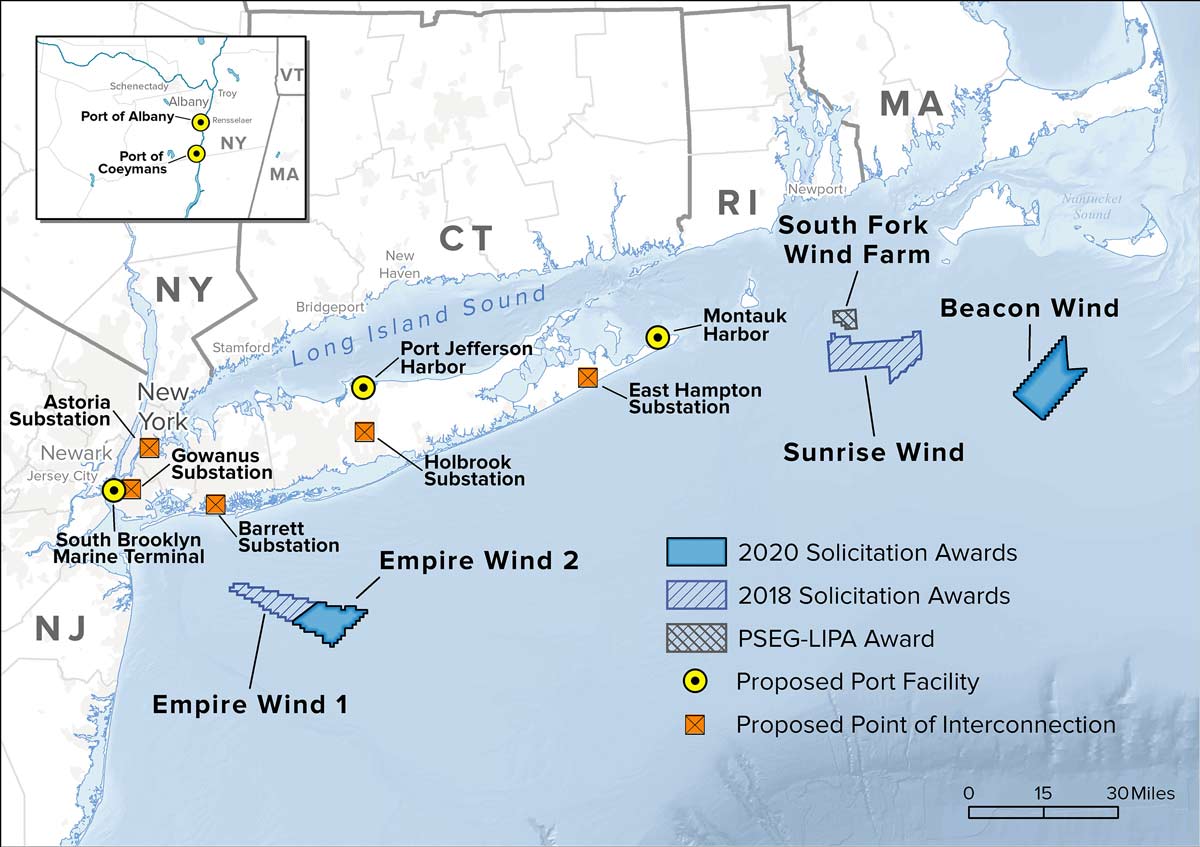

On Friday, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, or BOEM, proposed leasing eight new areas to offshore wind developers off the coast of New York and New Jersey in a shallow zone known as the New York Bight. The agency says the proposed lease area has the potential to host more than 7 gigawatts’ worth of wind turbines, or enough to power more than 2.6 million homes with emissions-free electricity.

It’s a step toward the Biden administration’s goal of developing 30 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2030. The new leases are also an essential first step to enable states like New York and New Jersey to fulfill their own clean energy goals. But there’s still a long road ahead before turbines can be planted in those plots, and experts warn the agency is not prepared to manage all the new development.

In keeping with Biden’s promise to create good-paying jobs and ensure that the energy transition benefits disadvantaged communities, BOEM will attach a number of stipulations to the leases. Developers may be required to “make every reasonable effort to enter into a project labor agreement” — basically an agreement with union labor — for the construction of the wind farm, which the North American Building Trades Union applauded. There will also be mechanisms to ensure that projects provide benefits to underserved communities and bolster the domestic wind manufacturing industry. In an effort to address concerns from the fishing industry that it has been left out of the conversation, developers may have to submit regular reports on how they are engaging with other ocean stakeholders.

The agency will be taking comments on the lease areas and stipulations for 60 days before making a final decision to auction them off.

There are already 16 commercial active offshore wind leases along the East Coast, including five projects under contract with the state of New York and one under contract with New Jersey. Together, the two states have a target of bringing 16,500 megawatts of wind power to their shores by 2035, enough to power about 9.2 million homes.

While the federal government is responsible for deciding when and where to issue leases for offshore wind, state clean energy goals are key to ensuring projects actually get built. After obtaining a lease from BOEM, developers must then look for buyers for the energy their projects would produce, like a state government or utility. Anne Reynolds, the executive director of the Alliance for Clean Energy New York, a coalition of renewable energy businesses, told Grist the new leases will benefit electricity consumers by increasing the competition when the two states solicit for new contracts.

“We don’t want to have just one company bidding on a contract because the ratepayers of New York are depending on competition to keep the prices as low as possible,” she said. “So it really helps both NJ and NY that there will be more lease areas.”

Reynolds said the Alliance for Clean Energy is hoping New York’s next solicitation for power contracts will be in 2022, after these new leases are sold.

It will take years for these projects to get up and running. Once a wind developer has a contract, it needs to go back to BOEM to apply for permits, which involves extensive environmental review. It also has to put in a request to the local grid operator for interconnection to the grid, which can take three to four years, said Reynolds.

The Biden administration is moving fast to open up more of the U.S. to offshore wind. Friday’s announcement follows another BOEM decision issued the previous week to explore offshore wind potential in the Gulf of Mexico. The White House also announced in May that it had identified two areas off the coast of California for potential wind development. Miriam Goldstein, the director of ocean policy at the Center for American Progress, a liberal research institute, said the new leases were great news but expressed concern that the agency was not adequately resourced to handle all of this development.

“This is a new industry, and it’s really important to get it right from the start,” she told Grist. One issue is that while BOEM has some regional offices in the Gulf and in Alaska to manage offshore oil and gas drilling, it doesn’t have any regional offices yet in areas where there will be major wind activity. Goldstein also said there needed to be more funding for research to assess how these projects will affect fisheries and other industries that need access to the waters.

“Along with this great announcement, there needs to be an awareness that without people there to staff it, and without the investment in science and information, it will be hard to make good decisions for a big offshore wind build-out,” she said. “So we need to invest in those aspects as well. And I would say urgently.”