In the fight against climate change, the $300-billion U.S. logging and woods products industry has positioned itself as a purveyor of “natural climate solutions.” The idea is intuitive: Trees are the ultimate renewable resource. After they are cut they can be replanted, absorbing carbon once again as they mature.

Wood energy succored Homo sapiens and its ancestors for millions of years, the argument goes, and only during the last couple of centuries was it replaced with fossil fuels like coal. As our civilization begins the slow process of jettisoning fossil energy, logging interests assure us that wood products are not a retrogression but a way forward. The industry claims that forests that are felled sustainably — for construction, say, or for burning to produce electricity in utility-scale power plants — can provide jobs and energy, stimulate the economy, and even reduce society’s net carbon emissions.

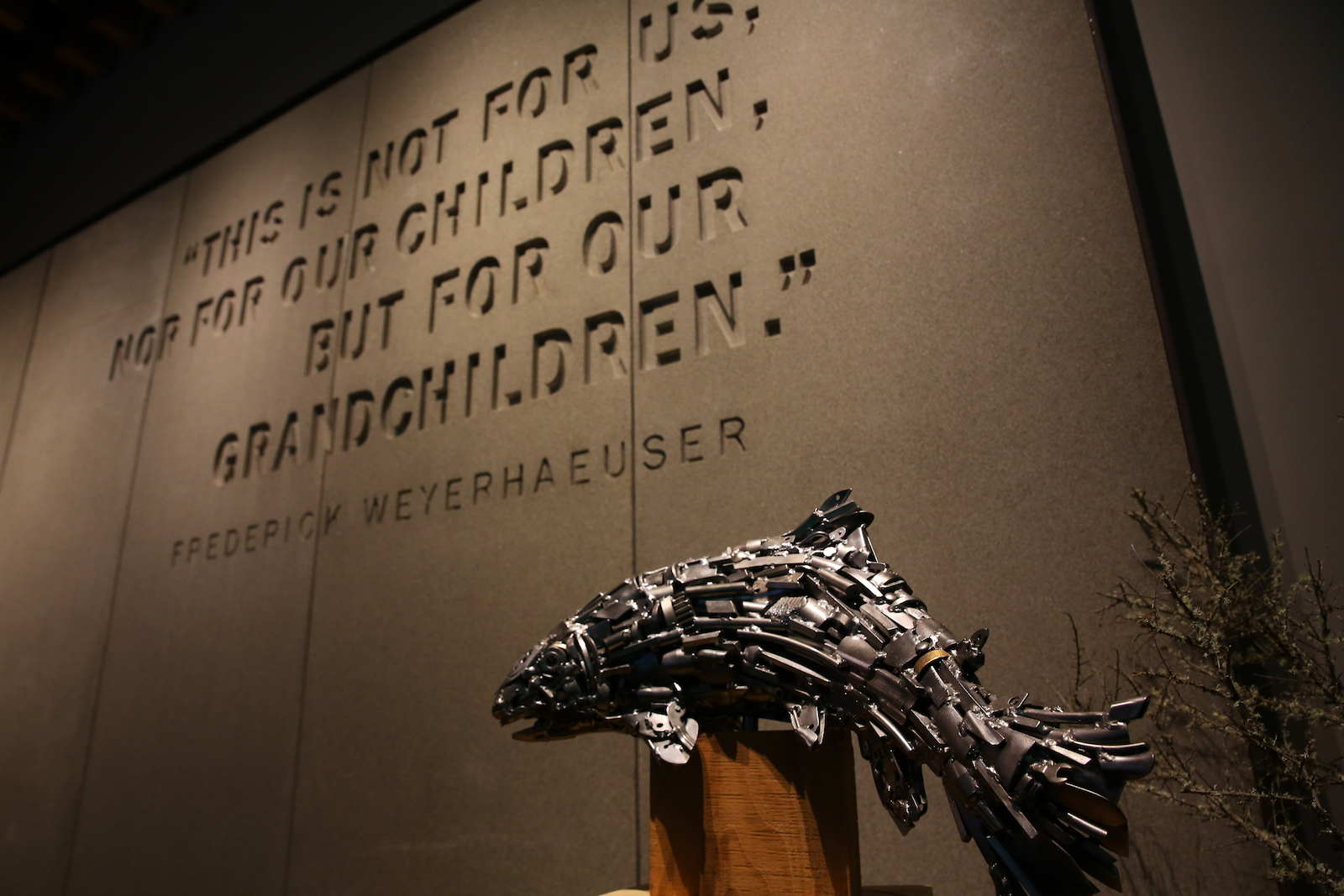

Weyerhaeuser, the world’s largest private owner of timber as well as its largest paper and pulp company, now markets how “wood products help remove and store CO2 and reduce the impacts of climate change.” The U.S. Industrial Pellet Association, a lobbying group for the biomass industry, proclaims that burning wood pellets from logged trees is “one of our best available tools to mitigate climate change, and achieve renewable energy goals.” The National Alliance of Forest Owners, a timber industry lobby group, has trumpeted “the important role sustainably managed forests and forest products can play in mitigating climate change.” In 2020, the CEOs of dozens of forestry businesses announced “an agreement of principles” stipulating that logged forests are beneficial for the climate.

This rosy view of logging, however, is hotly contested. In 2020, more than a hundred climate and forest scientists submitted a letter to Congress advising lawmakers not to trust the industry’s sustainability claims. There is no evidence, the scientists said, “to support increased logging to store more carbon in wood products, such as [for] buildings,” no evidence to “support the burning of wood in place of fossil fuels as a climate solution,” and no reason to support “legislative proposals that would promote logging and wood consumption,” as industry has lobbied for. The scientists counseled instead, to mitigate the climate crisis, the U.S. would need to “shift away from consumption of wood products and forest biomass energy.”

Nevertheless, the industry has garnered some allies among green groups. The signatories of the 2020 “agreement of principles” included conservation nonprofits like the Environmental Defense Fund, the American Forest Foundation, American Forests, and the Nature Conservancy, or TNC, the largest and wealthiest nonprofit conservation organization in the U.S. These groups signed on to natural climate solutions as “optimiz[ing] the carbon potential of the private working forest [through] the manufacture of sustainable forest products,” and they signaled their alignment with dozens of timber and forest products companies in support of “working forests” and “managed forests” — industry euphemisms for logged forests.

The entanglement of the wood products industry and these nonprofits stretches beyond the 2020 agreement. The Environmental Defense Fund, the American Forest Foundation, American Forests, and TNC are also members of the Forest-Climate Working Group, a political advocacy organization, alongside scores of wood product companies, including Enviva and Drax, biomass energy behemoths whose carbon-intensive operations have polluted U.S. communities and destroyed U.S. forests. The Forest-Climate Working Group’s policy platform for Congress urges the use of more wood in buildings, including in federal buildings, an expansion of state programs that promote the use of more wood products, and an increase in funding for federal Wood Innovation Grants “to stimulate … new forest product uses, and new or expanded forest products markets.”

These efforts are ostensibly in pursuit of a climate-friendly economy, the working group’s members having “found common ground on forest-related solutions to climate change” while representing a “unified voice across the U.S. forestry sector.” But some critics have called the Forest-Climate Working Group a greenwashing operation. “They give credence to the false narrative that expanding wood markets is essential to solving the climate crisis,” said Danna Smith, executive director of Dogwood Alliance, a conservation nonprofit in Asheville, North Carolina.

In the case of The Nature Conservancy, in particular, the ties to timber interests have sometimes been explicit. In 2006, TNC received a $1 million gift from the timber behemoth Weyerhaeuser that included a statement that the two entities “agreed to work collaboratively to improve their understanding of managed forests.” Until recently, millionaire hedge fund manager and major Enviva backer Jeffrey Ubben sat on a TNC investment advisory board and on Enviva’s board simultaneously. (In response to inquiries from Grist, a TNC spokesperson said that Ubben “had no governing authority” in his role and “is no longer affiliated with The Nature Conservancy in any capacity.”)

TNC’s entanglement with logging interests has made enemies of other green groups that might have been natural allies. On April 5, a coalition of more than 150 conservation, environmental, and social justice organizations signed an open letter to the Conservancy’s CEO, Jennifer Morris, charging that TNC was “promoting policies that favor the financial interests of the industrial logging and wood products industry at the expense of solving the climate crisis, protecting nature and advancing environmental justice.” The coalition demanded that TNC stop “promoting false climate solutions” that “center the financial interests of large lumber, pulp/paper, biomass/wood-pellet and other corporations.”

This was effectively a declaration of war in the genteel world of environmental nonprofits. Two of the authors of the letter, Dogwood Alliance’s Smith and the Reverend Leo Woodberry, pastor of the Living Kingdom Temple in Florence, South Carolina, co-edited an accompanying 35-page report titled “The Nature Conspiracy,” which focused on the effect of pro-logging politics in the poorest parts of the coastal plain states of the American South.

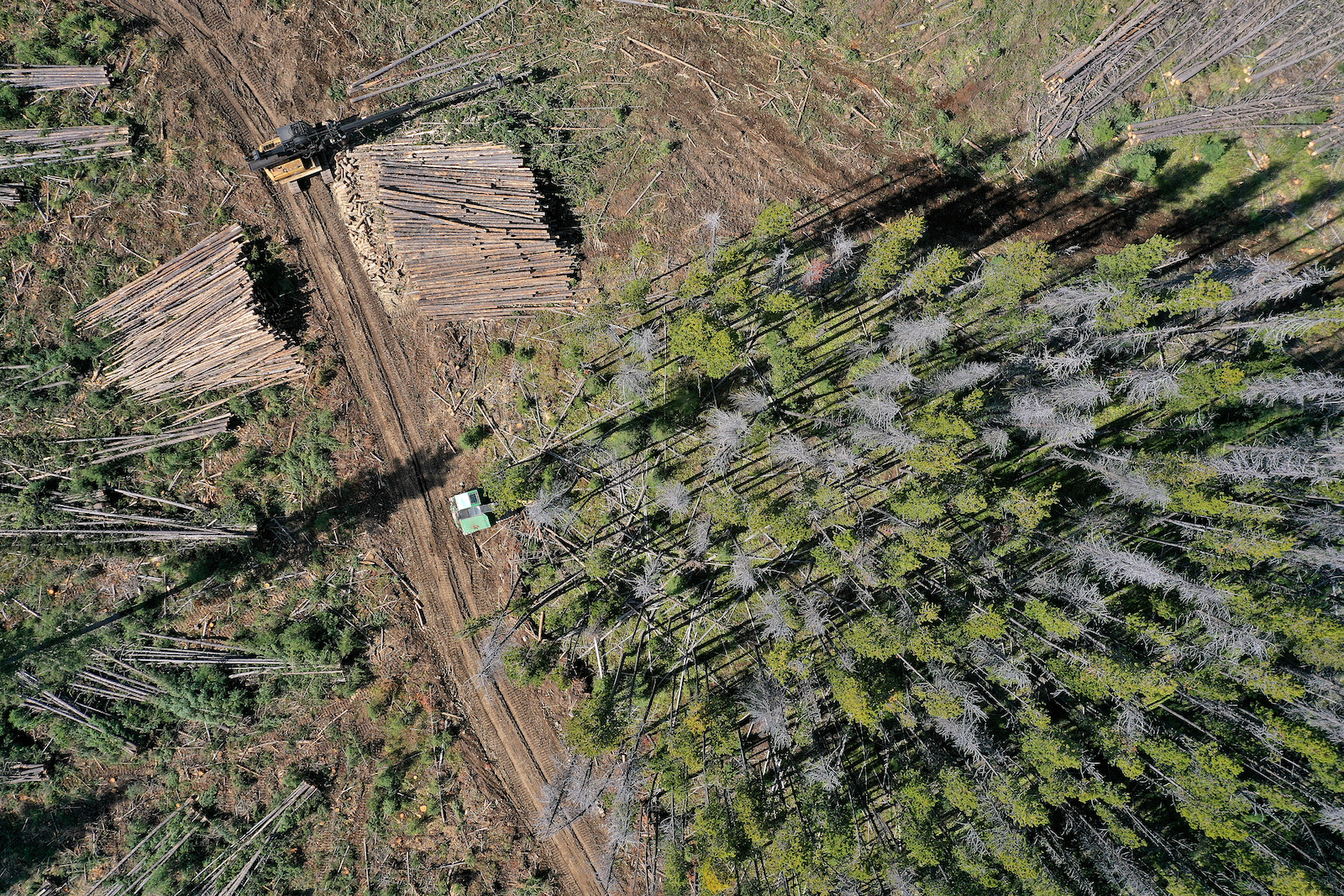

The report cites data showing that southeastern states were logged at four times the rate of the Amazon Basin during the first decade of the 21st century, making the region the most logged place on the planet. The insatiable demand for consumer wood products has been the primary cause of deforestation there, but the growing new demand is for wood pellets that are burned in overseas biomass plants to produce electricity, primarily in Europe. Smith calls the rush for wood pellets the most concentrated assault on southern forests since the invention of paper towels. The value of exported pellets in the U.S. has grown from around $250 million in 2012 to over $1 billion in 2021.

Smith, who says that Ubben was removed from his advisory role at TNC only after she told the nonprofit’s CEO that it constituted a conflict of interest, believes that TNC’s ties to the wood pellet industry should be enough to make it a pariah in environmental justice communities. “Logging for biomass is in rural African American areas, the Black belt of the U.S. south,” she told me. Not only is logging for all kinds of products — pellets, paper, pulp, lumber — concentrated in the Black belt, so too are many of the pellet mills, whose toxic emissions have sickened residents.

A TNC spokesperson told Grist that “The Nature Conspiracy” contains “factual errors and misinformation,” and emphasized that TNC’s position is that “bioenergy is not carbon neutral.” The spokesperson insisted that TNC has no involvement in wood pellet production and instead “focuses on the use of biomass that is a by-product of forest restoration and management activities such as thinning fire-prone forests.”

“While both TNC and The Dogwood Alliance share a commitment to working on forest conservation, climate change and environmental justice issues, we must also share the knowledge that reasonable people can disagree on approaches,” the spokesperson said.

Last September, I joined Smith for a trip across a stretch of the Black belt where North and South Carolina meet in the watersheds of the Pee Dee and Lumber Rivers, a hundred miles from the Atlantic coast. The area is heavily logged, and at just about every bend of the road there were vast clearcuts, ugly stretches of land that had been scalped. The dominant industries in this part of the Carolinas are those that feed on the forests: wood pellet mills, paper mills, pulp processors, and power plants that burn wood chips. “You can go anywhere across the coastal plain and find the same dynamic,” said Smith as we drove. “I’m 55, and in my lifetime I’ve seen a landscape-level change.”

Smith grew up in South Carolina, acquainted with swamps, cypresses, snakes, and the bewitching light of the wetland woods. After a dispiriting stint in corporate law, she turned to full-time environmentalism, joining Dogwood Alliance in 1997 and becoming its executive director at the age of 30. “I knew how to gather evidence and build a case,” she told me, “to advocate for the trees and the forests.”

We were headed to the 2,000-person, majority-Black town of Britton’s Neck in Marion County. We passed dozens of clearcuts, the land gray and barren, the slash from the downed trees in sad, jumbled piles. These were followed by plantations of hybridized pines, non-native, bioengineered, planted in rows, even-aged, and, hewing to industry practice, soaked in chemicals to keep the insects off.

The tops of the pines formed unbroken eaves, like the rooftops of rowhouses. “Can you see the tree line, homogenous all the way down?” said Smith. “Look at the perfect rows!” We turned onto South Carolina state highway 41, a few minutes north of Britton’s Neck, and passed a clearcut that formed on both sides of the road an empty prospect as far as the eye could see. The cut went on for miles. “And it keeps going, one after another. These are our southern forests. They’re not ecosystems. They’re fiber farms, corporate plantation croplands. This is what TNC is supporting.”

Smith had arranged a meeting in Britton’s Neck with Reverend Woodberry, a community organizer who had been dubbed “the EJ pastor.” Woodberry made a name for himself in the environmental justice community as one of the chief planners of the 2017 People’s Climate March in Washington, DC, which is where Smith met him. The two joined forces that year to help organize residents in Hamlet, North Carolina, to stop construction of an Enviva pellet plant. The effort failed, but in the course of it they became fast friends.

Woodberry is a fierce-looking 69-year-old who likes to bring environmentalism to the pulpit, making connections, for example, between the rivers that became blood in the Biblical Book of Revelation and red tides of toxic algae. “If we’re stewards of the Earth,” he once told a reporter, referring to the Book of Genesis, “we’re supposed to be doing something about this.”

One of his projects in South Carolina has been the documentation of how logging of wetland forests has led to an increase in flooding. It’s well known among ecologists that intact forests, with their extensive root systems and firm soil, absorb more water during storm events than logged forests. To experience up close the flood devastation that logging brings, however, is altogether different. “We’ve been in homes where the flooding was so bad the floor has fallen in, and you can peer in and see the ground,” Woodberry told me over the phone before I arrived in the Carolinas. “We’ve seen homes totally taken over by black mold, where children are sick.”

When I met him, the reverend was accompanied by two members of the Concerned Citizens of Brittons Neck: Johnny B. Graves, 78, and Marvin Woodberry, 66, the reverend’s cousin. The Pee Dee River flows near town, and in 2018, when Hurricane Florence hit, the river leapt its banks, and Johnny B. was evacuated along with some 2,000 residents. Marvin told me he has fled his house three times in the last five years due to flooding. After Hurricane Matthew in 2015, Woodberry tested the local drinking water and discovered it had been infiltrated with pesticides and other chemicals from the surging river, along with contaminants from overflowing sewage systems.

Seeing all this havoc was personal for the reverend. “This is an old community, formed in 1749,” he told me. “My family came from here. My uncle says we’ve been here since slavery.”

We came to a halt at a section of cracked tarmac that was the terminus of the last big flood, during Hurricane Florence. Marvin showed me a map of town on his phone. He pointed to an area southeast of where we stood, a half-mile distant, that had been repeatedly logged. Beyond the logged area was the Pee Dee River. “It’s all through there the water comes, where those trees used to be absorbing the water,” Marvin told me. “We got to stop this. We got to keep our trees.”

“We got to keep our trees!” echoed the reverend.

At the banks of the Pee Dee River along a dirt road, we came to a stretch of wetland where tall old trees still stood, and the banks sloped to the sleepy black water. It was unlogged land, and it happened to be the spot where Marvin had been baptized when he was a young man. Cypresses towered above us, shaggy with vines, disheveled, their wide trunks furrowed and buttressed. The river ran glassy and slow, the sun shone in clear azure sky, a lone cicada rattled, and a breeze whispered in a stand of loblolly pine. To my northern eyes — I had never seen cypresses in the flesh — it was a marvelously exotic scene. To Leo and Marvin Woodberry, it was native ground, and that it hadn’t been logged was meaningful in a way no outsider could comprehend.

The southern coastal plain has become home to biomass mills that gorge on the region’s forests and turn them into wood pellets. The biomass industry asserts that wood pellet production is clean, green, and sustainable. The people I met in the shadow of the mills disagreed. Debra David, a 64-year-old homemaker turned activist, lives three miles from an Enviva mill in Hamlet, NC, which commenced operations in 2019 — the year, as it happens, that David started having trouble breathing. I met with her last autumn in a one-room Pentecostal church in town, where she and a neighbor and fellow parishioner, 50-year-old Debbie Short, described the collapse of their health.

“I use a nebulizer now. I can hardly walk,” said Short. She attributes her exploding case of asthma to air pollutants from the mill.

“I never had respiratory problems before Enviva came,” David told me. “Two years ago, I went to the hospital, it got so bad. They put me on a ventilator.”

Debbie Short, left, and Debra David, right, live near Enviva’s wood pellet mill in North Carolina. They both have health problems they attribute to pollution from the mill. Photos by Christopher Ketcham / Grist

Both women are Black, and both live in a relatively impoverished community: Hamlet’s poverty rate is 29 percent. They told me that widespread health problems among friends and family began with the powering up of the pellet mill. Short’s son, who is 29, gets headaches daily. David says her adult son suffers routine nosebleeds, though he never had them prior to Enviva’s arrival.

That the community is being sickened should not come as a shock. A 2018 investigation by the Environmental Integrity Project, or EIP, found that of 21 wood-pellet processing facilities it looked at across the South, more than half “either failed to keep emissions below legal limits or failed to install required pollution controls.” At least a third of the facilities investigated were operated by Enviva.

(In response to Grist’s request for comment about the EIP report, an Enviva spokesperson said the report has “numerous false statements about Enviva” and that “all our plants operate well inside the U.S. federal and state regulatory emission standards, presenting no risk or issue to public health or the environment.” The spokesperson insisted that Enviva has never received any community complaints about its plant in Hamlet.)

Manufacturing wood pellets is a filthy job. The logged material is dried in a wood-fired process, then pressed into pellets. Each step produces air pollution. EIP’s investigation found that emissions from the 21 facilities — which together produced 16,000 tons of air pollutants annually — included nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide, and volatile organic compounds. The pellet mills spew the particularly noxious type of soot called PM 2.5, which is so fine that it can pass deep into the lungs and depress lung function, worsen asthma, and trigger heart attacks. When exposed to sunlight, volatile organic compounds and nitrogen oxides transform into ozone, which is especially dangerous to children and the elderly.

On top of these environmental justice concerns, there is the climate cost of biomass. The industry’s vaunted declaration that it’s a carbon-neutral energy source would seem at odds with the fact that burning wood pellets for power emits more carbon per unit of electricity produced than coal. The industry, along with many European governments that have widely subsidized biomass as green energy, counters that these emissions are rendered moot, because trees are regrown in the logged trees’ place to absorb whatever carbon is released with burning. The staking of climate neutrality, however, ignores the all-important time frame of the need for decarbonization in the next two decades to avoid catastrophic warming.

In 2021, 87 scientists and economists, taking stock of the evidence, charged biomass proponents with a kind of carbon accounting fraud. The industry and its supporters in the European Union, they said, had failed to account for the effect of logged trees that no longer remove carbon from the atmosphere, the massive loss of carbon in soils due to logging’s ground disturbance, and the carbon emissions from the fossil fuels burnt to topple and haul trees and process them into pellets.

Smith and Woodberry have questioned why TNC has never spoken publicly about logging’s immense carbon impacts. A group of researchers from NASA, the U.S. Forest Service, and the World Resources Institute found that logging was the single largest driver of carbon emissions from U.S. forests between 2006 and 2010, five times more impactful than fires, land-use change, insects, drought, and wind damage combined. An open letter to Congress published last November and signed by hundreds of scientists concluded that “greenhouse gas emissions from logging in U.S. forests are now comparable to the annual CO2 emissions from U.S. coal burning.”

“In 2020, we joined environmental and justice groups and scientists from across the nation in an effort to engage The Nature Conservancy in conversation about this ongoing forest crisis,” Woodberry and Smith wrote in their editors’ introduction to the “The Nature Conspiracy.” They asked that TNC make a public statement about logging as a driver of carbon emissions in U.S. forests and commit to advancing environmental justice in communities on the front lines.

TNC, as Woodberry and Smith put it, “listened at first, but then declined to act.” The attempt by the coalition they built to engage the nonprofit was in fact a 10-month endeavor, involving multiple letters, phone calls, and meetings with TNC officials, including one directly with Morris that lasted four hours, according to Smith.

“The forestry industry is just like the fossil fuel industry. It is extractive, polluting, climate-disruptive, and destructive of biodiversity,” Smith told me. “TNC doesn’t want to hear this.”

In 2015, a conservation biologist at Duke University named Stuart Pimm, who specializes in extinctions, wanted to know whether the system of land protection in the U.S. was up to the task of preserving biodiversity at a time when many species are collapsing. He looked first at the land trusts of the Nature Conservancy. With annual revenue of over $1 billion, TNC has funded the purchase of many millions of acres of land trusts as conservation easements intended to be protected from development.

Pimm, to his surprise, discovered that one of the lowest concentrations of protected land was in the southeastern U.S., which is more biodiverse than most other parts of the country. It also has the highest rate of endemism, defined as species that only occur in a particular area and nowhere else.

Pimm expected that the planet’s most endowed conservation group would be more attentive to places teeming with life. Curious as to why there were so few TNC acquisitions in the American South, the nation’s biodiversity hotspot, Pimm believed he found the answer by overlaying on the map of land trusts a second map of U.S. counties coded by income and wealth. Most of TNC’s land acquisitions were in the richest counties, overwhelmingly in the Northeast, New England, the Upper Midwest, and in a selection of wealthy enclaves elsewhere across the country. Failing to protect the more biodiverse but economically bereft regions of the South amounted to “a spectacular failure of TNC’s national leadership,” Pimm told me.

In August 2021, Pimm, a self-described Christian, joined with Michael Malcolm, an environmental justice pastor and executive director of the People’s Justice Council, to write a letter to the chief scientist at TNC, Katherine Hayhoe, one of the few publicly-prominent evangelical Christians who believe in climate change. The intractable problem facing TNC, as Pimm and Malcolm remarked in the letter, is that it “now has a very unfortunate reputation for dismissing science for its own political convenience.” The group’s positions “on issues involving climate change and biodiversity in the southeast USA,” they charged, “are unconscionable.”

“Our Christian values teach us to stand and speak out against the things that harm community,” Pimm and Malcolm told Hayhoe. (Hayhoe, through intermediaries at TNC, did not respond to Grist’s requests for comment). “Your not speaking out against current TNC practices harms nature, harms people, and it harms you and the reputation you have worked so hard to establish.”

Hayhoe didn’t respond. “We got nothing. Zip,” Pimm told me. “It showed a level of arrogance that I found was exceptional.”

The Fund for Investigative Journalism provided additional funding for this article.