The clean energy revolution came to New York under Governor Etosha Cave, when a group of sustainability wonks just happened to slip into complementary leadership roles all at the same time. Over the next five years, they faced down hurricanes, a NIMBY backlash, and a white-knuckle election where public sentiment swung from condemnation to approval. Advanced nuclear power flourished. The shores of Long Island sprouted a forest of turbines. The team reeled from one clean-energy project to the next and somehow managed to shut down all fossil-fueled electricity in the state by 2035. Or at least they were on pace to do that, if they’d had time to finish the game.

And I got to be in the room when it all went down — because it happened on a board spread across my dining room table in Berkeley, California. I’d been waiting for something like this because, after years of writing about how to continue civilization without wrecking the world, I kept thinking that a game might be an easier way to help people weigh the thorny consequences that come with every strategic choice. The classic game Monopoly, for example, is all about balancing the risk of going broke against the risk of sitting on cash and passing up opportunities: It’s a lesson in optimizing for an unknown future (a challenge that will sound familiar to climate-policy wonks). A game forces people to grapple with tradeoffs in a way writing can’t.

So, the moment I heard that the nonprofit City Atlas was making a climate board game called Energetic, I wrote one of its founders, Richard Reiss, to beg for it.

Narrative writing is great for morality tales, whodunits, and quests. But it’s not always a great way to explain a bunch of numbers (a well-made graph can work wonders). And it’s a difficult way to illustrate how complex systems work, or even not-so-complex systems. You can’t learn to ride a bike by reading about it. And so, as I’ve labored to illustrate why cheap renewable energy can be expensive, why industrial farming is an important part of a sustainable food system, or why feeding people controls population more effectively than starvation, I’ve longed to find a way to give people a toy model of each system that they could play with.

It was with all that in mind that a group of climate wonks gathered around my dining room table to play Energetic, the hot-off-the-presses board game in which players race against time to build enough clean electricity to power New York state. It’s a cooperative game, like a version of Pandemic where you are trying to squelch fossil fuels rather than an outbreak (hullo, fellow board-game geeks!).

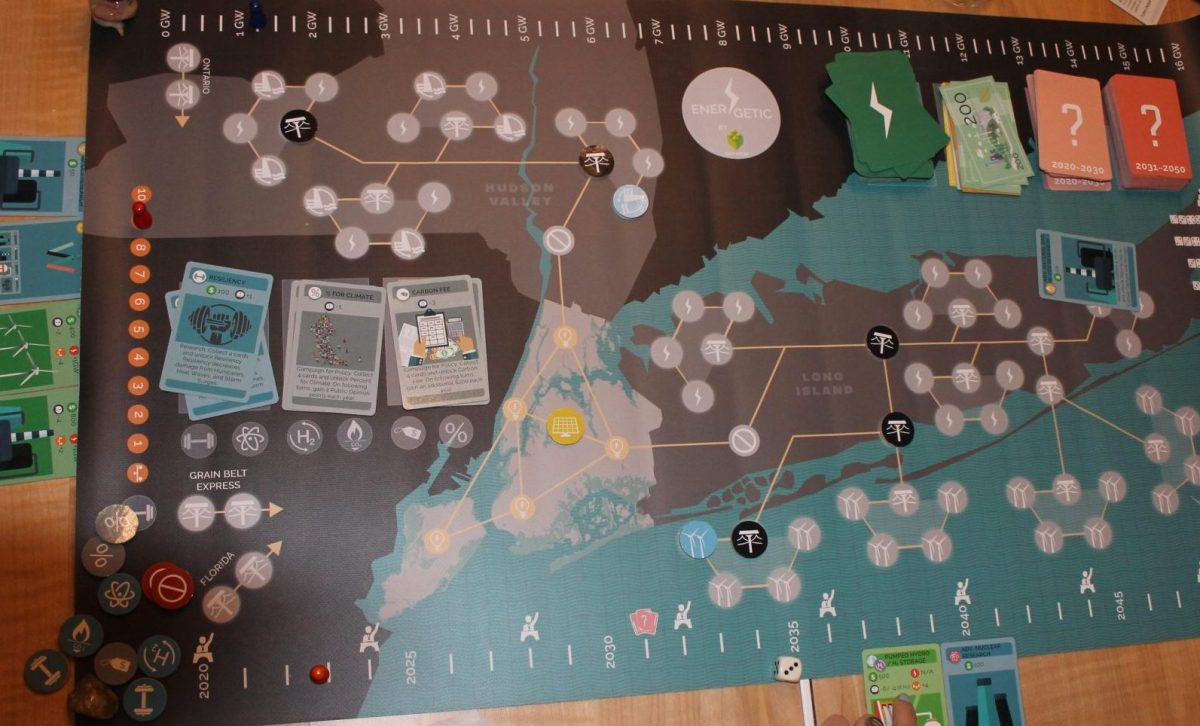

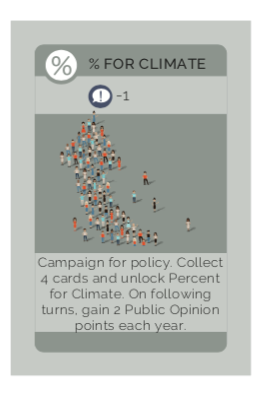

Your team aims to build a supply of 16 gigawatts of clean energy before 2035 while also managing money, public opinion, and grid stability. Each player takes a role with special abilities. There’s a politician capable of swaying public sentiment, an engineer who can advance technological research, a money-generating entrepreneur, an activist, and a journalist. Each turn is a year in which players get more money from taxpayers, and two new cards representing opportunities to work on policy, research, or a new power plant. The game comes with explanations, but at some level it’s up to the players to come up with their own interpretations: When the politician uses her power to improve public opinion, perhaps she buys TV ads or hands out bribes.

“I warn you. I’m predisposed to fucking hate this game because I’ve been playing it for 30 years already,” said Saul Griffith, an inventor turned political advisor. Griffith took the role of the journalist, documenting progress (or “snarking”) from the sidelines. Etosha Cave, whose company Opus 12 removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and turns it into polymers and jet fuel, became governor of New York. Leslie Aguayo, who works for the nonprofit Greenlining Institute, assumed the role of engineer. Elena Foukes, a manager at Tesla and founder of an energy startup, played the entrepreneur. Sam Arons, Lyft’s head of sustainability, took the role of activist.

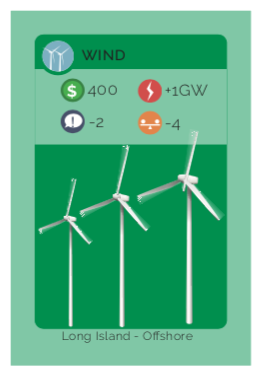

After reviewing the rules and unwrapping burritos from a restaurant down the street, the game got underway. It was 2021, and Aguayo, our engineer, started by placing half a dozen transmission-line tiles to connect New York City to outlying areas including Long Island Sound, where the activist and entrepreneur worked together to erect a forest of offshore wind turbines. “Oh, to have such eminent domain in real life,” Arons mused.

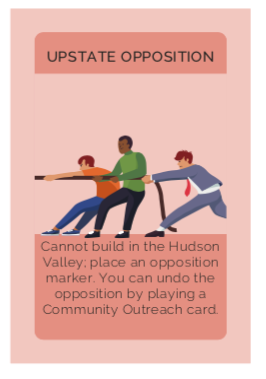

City Atlas

The game turned out to be a massive balancing act. As the energy from that offshore wind farm surged and receded (depending on the zephyrs), it was tricky to keep a constant voltage streaming to the state’s electrical outlets. In an attempt to stabilize the grid, the players built a reservoir in the Hudson River Valley, which would act as a giant battery. But residents got mad — presumably because their farms and vacation homes were flooded — and by the end of the second year public support for their efforts had evaporated. Responding to public outrage, power outages, and a lack of money would have been a lot easier if the players had more time, but they wanted to decarbonize by 2035. Plus, it was a weeknight, and I like to be in bed by 10:30.

As the team headed into their first election year, Griffith excoriated the others: “Governor Etosha’s popularity is at an all-time low, which is a little bit shocking given that she presides over AOC’s district, who was a huge advocate for the Green New Deal,” he said. “We are midway into the 2020s and there’s nothing to show for it. The people are ready to revolt.”

Maybe, Griffith speculated, that’s because Governor Etosha should have been more ambitious. Or maybe it’s because, in addition to building turbines and dams, the players had also been trying to pass a carbon tax and a program to win over public opinion. (The players interpreted this as something like a carbon dividend or a green-job training program, while game designers had thought of it as an education program).

City Atlas

If Griffith’s commentary peeved the governor, she hid it well, responding with a plan to abandon the carbon tax and tap her special ability to improve public opinion with a giant ad-buy. “Governor siphons money into Facebook ads,” Griffith crowed.

That strategy, a surge of young voters, and a lucky die roll was enough to win the election.

“I can’t believe it! You pulled the rabbit out of the hat,” Griffith marveled.

Other players began chanting: “Four more years!”

City Atlas

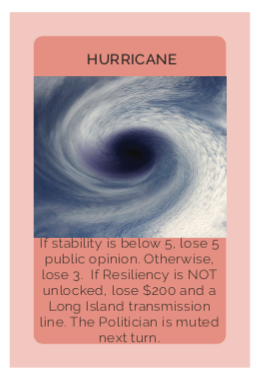

To succeed in Energetic, players have to make use of opportunities when they arrive. So when they got the cards needed to complete research on the next generation of nuclear reactors, they quickly set about building those plants upstate. They weathered two hurricanes and a storm surge but decided to pack it in at 2025, a third of the way to their goal, as it was close to my bedtime.

City Atlas

Griffith the journalist was not happy (“because you fuckers failed me on a two-degree world!”), but Governor Etosha pointed out that the gamers were on pace to build a complete clean electricity system by 2035.

“I like that climate optimism,” said Foukes, the entrepreneur.

Energetic isn’t going to become the next Settlers of Catan, because it’s primarily designed for instruction, rather than addictive playability. But it’s way more fun than reading a bunch of scientific studies and reports — and that’s the competition.

“It’s actually pretty impressive,” Arons said. “I kept thinking, ‘Oh, they thought of that? Wow, they thought of that!’”

Griffith pointed out that Energetic doesn’t provide a way to manage energy demand — paying people to turn off their air conditioning, for example — which would be a lot easier than building pumped-hydro reservoirs. Aguayo wished she’d seen more of her work reflected in the game. “I wish I could see where the lower-income folks are on the map,” she said. “I’d build there first.”

At the same time, the players acknowledged, too much complexity would render the game unplayable.

City Atlas

The game map remained in its uncompleted state after everybody had left. The players had been bold, happy to sacrifice public support to build clean power plants as fast as possible. But they hadn’t pushed too far: Governor Etosha won two elections while building 6 of the 16 gigawatts of clean energy needed to win the game. The wreckage of hurricane-ruined power lines still lay tangled on the ground, and waves lapped a little higher against the sea walls.