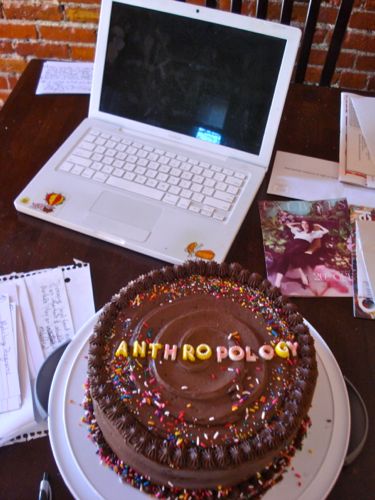

Photo: Erin Ross

Photo: Erin Ross

Food Studies features the voices of 11 volunteer student bloggers from a variety of different food- and agriculture-related programs at universities around the world. You can explore the full series here.

Since I moved from Pittsburgh to attend Boston University in August 2010, I’ve been repeatedly confronted with a rather daunting question: “What are you in school for?” I still have to pause before I tell people “Oh, I’m getting my Masters in gastronomy.” The exchange can get a little awkward here when they reply either, “Oh, so you’re studying the stars?” or they blink and say “Like intestines?” I then have to backtrack a little and tell them no, gastronomy is actually a liberal arts degree where, basically, “I get to research, read, and write about food.”

Often, the conversation stops here, but occasionally it takes an even worse turn than the foray into anatomical talk, if they ask me, “So, what are you planning on doing with that?”

This is not a question I currently have a solid answer for.

What I can tell them is that since I started the program, my reasons for being in it have evolved exponentially beyond my initial interest in food. This time last year, when I first enrolled, I wanted to tell people all about how I was a line-cook and a baker until two wrist injuries forced me to revisit my academic background in food (I managed to write a thesis on Martha Stewart, Amy Sedaris, and the feminist implications of the New Domesticity for a BA in English). The story of why I had chosen this field made sense, at least to me.

This year it seems so much more complex. I’ve struggled to tie together the different directions the five courses I took last year have led me in, let alone where I hope to wind up at the end of my second year.

For example, I started out last fall with a semester spent unpacking the historical significance of baking powder and how it has influenced cake recipe development. (For the curious: Baking powder made cakes easier and less expensive to produce than ever before. Recipes had previously required as many as 16 eggs to rise; substituting baking powder for some of the eggs saved both money and the effort of beating them.) Then I traversed through a semester of anthropological fieldwork, studying food stamp usage at farmers’ markets, and attempting to figure out whether it was a meaningful way of increasing food access options for low-income populations. And I got my hands dirty gardening at the Fenway Victory Gardens during a summer course in urban agriculture.

Throughout my first year I’ve learned a ton — about food, certainly, but also about the ways of studying it that I enjoy. I’ve discovered that I can do anthropological fieldwork and it’s a great research tool, but that maybe I’m happier with library research overall. This fall, I want to get out of the field and back to my comfort zone.

I’m taking two theory-based courses — Food Philosophy and Food and the Senses — so I’ll have plenty of opportunities to do just that. I’m also thinking that perhaps its time to revisit my dream of examining punk rock cooking zines in a more academic light. These are self-published recipe books, often vegan, and frequently influenced by the type of music the author listens to. I’d love to look at them in relation to the scholarship that already exists on manuscript cookbooks, and attempt to unpack what they say about the time they were written in and the communities they represent. There are plenty of questions I want to figure out answers to, after all — just not the one about what I’m going to do with my particular blend of food studies.