Palm oil is a dirty word for many environmentalists. Thousands of acres of forest, and the carbon-dense peat soils beneath, have gone up in flames, clearing the way for rows of oil palm trees. For decades, governments of Southeast Asia gave agricultural companies the rights to develop vast swathes of forest, and those companies turned wilderness into plantations as fast as they could.

That was the depressing story since the 1990s, but things have recently changed for the better. In areas dominated by the palm-oil industry, deforestation has plummeted. Plantation owners used to burn and cut an area the size of Yosemite National Park every year, but they leveled less than a fifth of that in 2020, according to the latest analysis by the supply-chain watching nonprofit, Chain Reaction Research. And this isn’t just a statistical blip. “This is the fourth straight year that palm-oil deforestation has been at a fraction of historic levels, and trending down,” said Glenn Hurowitz, CEO of the environmental nonprofit, Mighty Earth.

The news on deforestation around the rest of the world is not so encouraging. Forest loss has only accelerated since the 2014 United Nations climate summit, when a collection of multinational food companies and governments committed to stop it entirely. In the past four years, as the situation has improved in Southeast Asia, it has gotten worse in Brazil and other parts of South America as ranchers and land speculators convert forests into cattle pastures. It can feel like an impossibly big problem, but by zeroing in on the bright spots, you can get a glimpse into what it might take to stop runaway deforestation altogether.

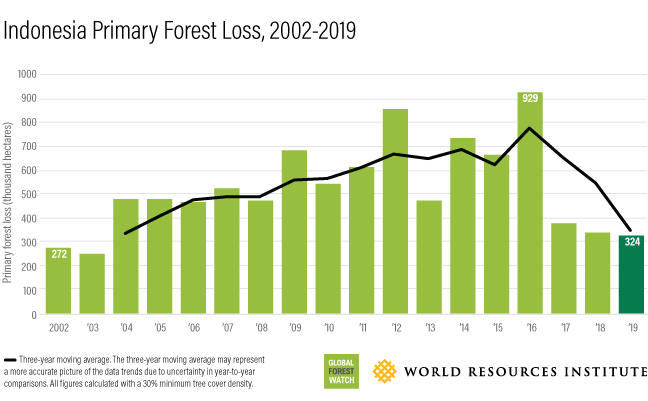

These days, Indonesia is looking like one of those bright spots. In 2011, the government of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono announced that it would stop handing out forest land for palm oil plantations. Suppliers would just have to make do with existing concessions. The move soon seemed woefully inadequate, as Indonesian forests fell faster than ever. But that policy change reverberated with the titans of the palm-oil industry, IOI Group, Cargill, and the biggest of them all, Singapore-based Wilmar International.

“Palm oil is controlled by just a few giant companies, and so those companies are able to exert pressure on all the businesses they buy from,” said Haseeb Bakhtary, who researches deforestation for the nonprofit Climate Focus.

Wilmar’s CEO Kuok Khoon Hong, was beginning to see that he might have the power to tip the entire industry toward saving, rather than felling, forests. The disastrous consequences of palm-oil development had become impossible to ignore: Singapore was choking on the smoke of burning forests, news reports were filled with images of stricken orangutans, and environmental groups were leading increasingly successful campaigns against companies that used palm oil in their products Over two tense days at the end of 2013, Hong, Hurowitz and other leaders hammered out a commitment (Grist has the tick tock on how that happened, here). By the end of 2014, every other major palm oil trader had done the same, telling their palm oil suppliers that those plantation owners who wiped out more forests would no longer have anywhere to sell their oil.

Still, deforestation in Indonesia kept rising. Forest fires flared and palm oil companies kept clearing land.

“We had hoped that the big companies would do their own monitoring and enforcement, but we found that companies like Korindo Group were able to clear 10,000 hectares and get away with it,” Hurowitz said. And so activists began guarding the forests themselves, using satellite imagery provided by Global Forest Watch, the online forest-monitoring program, and others. Mighty Earth, or another watchdog, wil now alert big palm-oil buyers and prompt a crackdown.

“If a supplier cuts down even a few hectares they will hear about it,” Hurowitz said. “Lately we have been struggling to find any major instances of deforestation.”

When big businesses — instead of fighting environmental protections — turn around and start backing environmental reforms, like Wilmar did, it makes it easier for governments to take more action. Indonesia has stepped up its efforts to stop forests from burning, and made its moratorium on palm-oil concessions permanent, said Liz Goldman who researches forest conversion at the World Resources Institute, a global research organization.

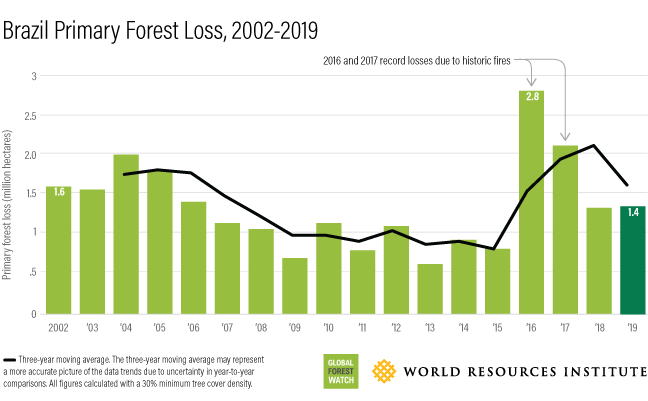

That’s the good news, but it’s only half the story. Spin the globe from Indonesia to Brazil, and you’ll find stark differences. There too, companies — many of them the same ones that clamped down on the palm oil trade — have made commitments to stop deforestation. But Brazil’s president, Jair Bolsonaro, seems to love wiping out forests, and only has acted to control forest burning under pressure from investors and other countries.

In Brazil, the big international traders have control over the soybean market, and their efforts to stop the conversion of the Brazilian Amazon into soy fields has been largely successful. But in parts of Brazil outside the Amazon, companies have been unwilling to back up their pledges by punishing their suppliers. And even if these corporations took strong action, that wouldn’t halt deforestation: Most of the forest cut down in Brazil turns into cattle pasture, and international companies only buy about 15 percent of Brazilian beef. It would take the coordination of domestic Brazilian businesses and a government that actually wants to halt deforestation to reverse the surge of Brazilian forest loss.

To be sure, there’s more to this story than the alignment of big businesses and governments. Basic economics also play a role: Palm oil plantations expanded fastest when palm oil prices were highest, so lower prices have translated into a drop in deforestation. The same basic economics work in Brazil, too. People can influence prices by choosing what they eat, Bakhtary said. If there’s less demand for beef, for instance, prices for cattle will fall, and ranchers won’t reap rewards for carving new pastures out of the wilderness.

Perhaps the economic slowdown and the pandemic also helped to keep Indonesian forests standing in 2020. Still, the last four years in Indonesia looks to Hurowitz like solid evidence that forest protectors have finally cracked the code: When governments and big businesses start backing up their words with deeds, and punishing those that break the rules, they might stop forests from falling.

Correction: A previous version of this story attributed a statement to the wrong researcher at the World Resources Institute.