I recently got an email from a reader asking me to check out a story entitled “Everything Is Organic & Non-GMO In Peru And Food Prices Are Insanely Cheap. This Is How.”

The reader asked me to investigate — although he also acknowledged that the piece was mostly a rant which, in typical internet fashion, didn’t actually explain the “how” promised in the headline. But still, I was intrigued. It’s always worthwhile to look beyond our own system, and our cultural blinders, for alternatives.

So I got in touch with Maximo Torero, an economist at the International Food Policy Research Institute who specializes in Latin America and teaches at the Universidad del Pacífico in Lima, Peru.

The problem with the assertions in that headline, Torero told me, is that they were pretty much all wrong.

“The prices in Peru are pretty high,” he said. “If you are middle class in Lima, for instance, going out to restaurants is equivalent to going out in Washington, D.C.” Perhaps you might be able to get an occasional deal at a farmers market, just like in the U.S. But overall, it’s not cheaper.

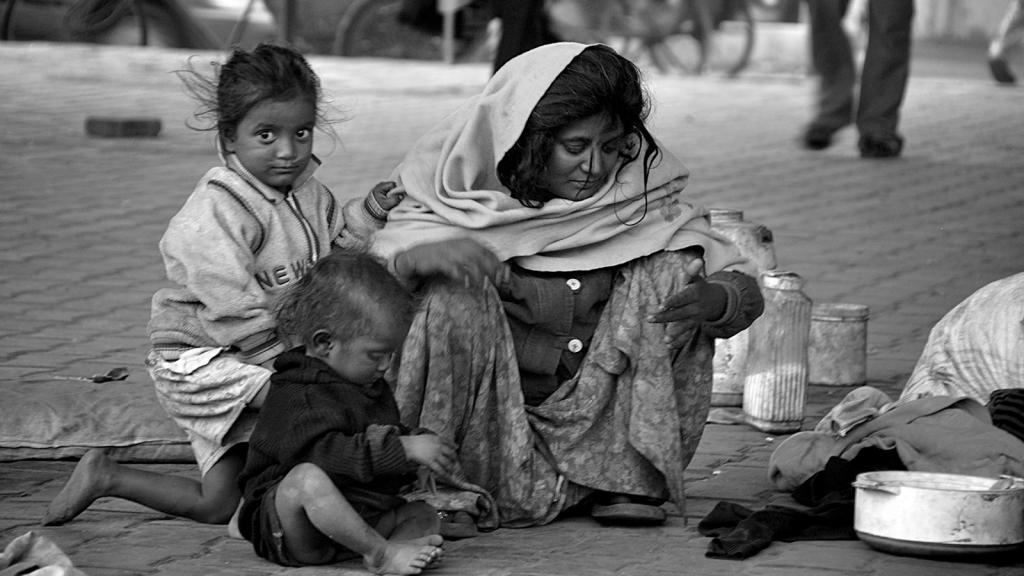

The average Peruvian household spends nearly 30 percent of its income on food, compared to less than 10 percent in the U.S., and people are much more likely to go hungry in Peru than in the states. More than 40 percent of pre-school children suffer from anemia there.

Is everything organic? I asked. He chuckled. “No, not much at all.” But he said that it is true that Peru has put a moratorium on the use of GMO seeds.

So, one for three. A more accurate headline might have been: “Everything is Non-GMO in Peru, Food Prices Are High, and Kids are Anemic. This Is How.”

The reason I think it’s worth fact-checking a rant on a dubious website (aside from the fact that I love giving readers what they ask for) is that I keep bumping into the conviction that if we could just get rid of biotechnology, we’d see a wonderful flowering of alternative agriculture. In fact, that was the basis of the debate I encountered when I started this series: Do we choose biotechnology or agroecology?

The example of Peru makes that divide look pretty irrelevant. Peru is on a good trajectory: In 1990, 32 percent of the population was undernourished, and now that’s down to 12 percent. Banning GMOs in 2013 hasn’t had a big effect, either positive or negative.

When I asked Torero what Peru was doing right, he talked about social programs. The state is feeding pre-school kids. It’s providing breakfasts to older kids in school. It has a program to pay poor families when they send their children to school, to remove the pressure for children to enter the workforce. The country has a solid macro-economic financial policy and has plenty of money to sustain programs like these.

Peru’s economic growth hasn’t been spread evenly across social classes, Torero said. The real key to ending hunger would be to reduce inequality by insuring that the poor have access to services like education and healthcare, so they can benefit from the growth. Brazil has done a better job with that, he said.

The problem with this stuff is that … it’s boring. (How many readers tuned out somewhere around “macro-economic financial policy”?) It’s a lot more exciting to claim you’ve discovered utopia, along with a simple solution for getting there. But genuine solutions almost always involve a tedious real-world slog, rather than a quantum leap into an alternative paradigm.

This does, however, touch on an important and generally unacknowledged undercurrent in the debate over food production. I think that people are actually gesturing vaguely at a larger concern when they talk about choosing between biotechnology and agroecology: They worry that the groundwork developing countries are laying today — the infrastructure, industry, and laws they are putting in place — will lock them into the same form of agriculture that we have in the U.S. But let’s save the question of technological lock-in for another post.