Q. My siblings and I recently inherited mineral rights on our mother’s property in West Virginia. We’ve already been contacted to lease them to an energy company for drilling. What should we do?

Jed Clampett Jr

A. The idea of “fighting climate change” is frustratingly abstract. Even if you understand its primary causes — i.e., extracting and burning fossil fuels — the acts of driving less, flying less, buying less feel so many steps removed. Your opportunities to directly obstruct fossil fuels from exiting the ground are probably … limited. (That doesn’t diminish the importance of the driving-flying-buying less.)

Which is why, when I received your question, I thought: “Wow, what an extremely tangible way to approach the fight against climate change!” You control a sliver of what so many environmental activists are fighting to keep in the ground.

Indeed, Adela Gondek, a professor of environmental ethics at Columbia University, told me that this is a perfect example of a problem discussed in her class. If you happen to control even a tiny bit of a very valuable resource, you have an ethical obligation to consider all the potential harms and benefits of exploiting it.

The ethical question of who we are obligated not to harm, Gondek explains, has changed in scope and content over time: “Are you thinking of more people than just those in your family, or your tribe, or your country? Are you thinking of other people, too, even if they’re harder to imagine?”

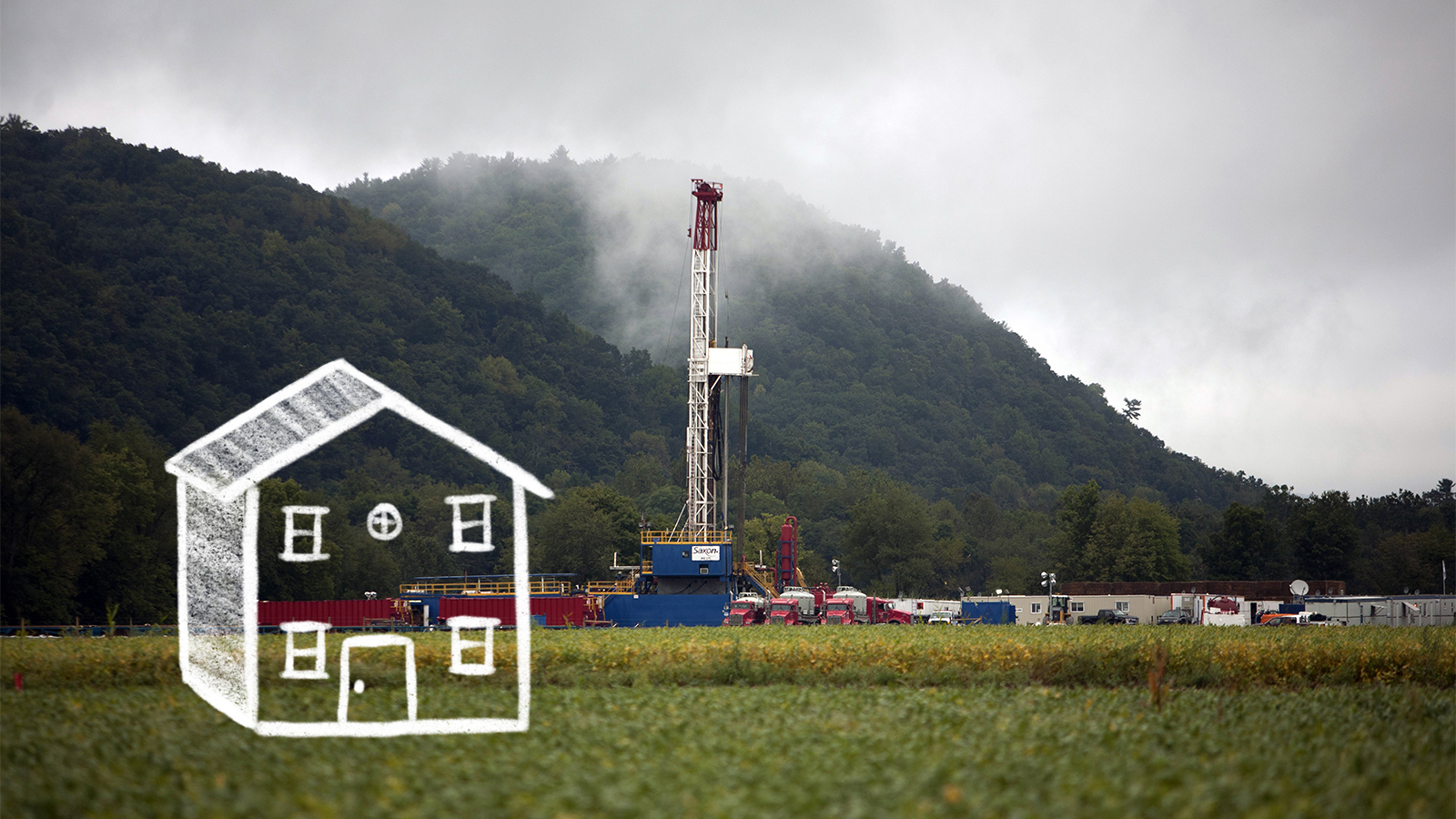

The harm to everyone — family, tribe, country, the world — is straightforward. You’ll be directly contributing to climate change by inviting an energy company to drill on your land; and there’s the strong likelihood of contaminating the nearby water sources and air in some way, and harming the people who depend on them.

The benefit? Leasing your mineral rights is seen as a way to make enormous profit with very little effort — but in practice, it’s often more complicated than that.

Perhaps you, Jed Jr., are already pretty environmentally inclined, happy to keep your own personal fossil fuels underground, and able to afford to do so. But if your co-inheritors could use the money — which, as you estimated in your original email, will probably amount to a few thousand dollars altogether — it’s on you to convince them that it’s not worth it. Let’s start with this: Drilling companies have historically lured lessors of mineral rights into a false sense of economic security.

Ron Gulla, a farmer-turned-environmental-activist in Washington County, Pennsylvania, has been dealing with the environmental and economic fallout of leasing drilling rights on his farm for over a decade. In 2005, the local Farm Bureau contacted him and his neighbors about leasing their land to energy companies.

Gulla, who had worked in the oil and gas industry, alleges that he agreed to vertical as opposed to horizontal drilling, aka fracking, which is what he ended up with. Fracking was a new practice at the time, and he had no idea of the environmental impacts that it would have on his land. Gulla estimates that he’s spent over $100,000 in legal bills over the loss of his farm, which he says was rendered inoperable because of water and soil contamination.

Now, years later, Gulla says that the leases caused enormous conflicts in his rural community, including financial loss. The pattern: A family would overspend, having been promised huge windfalls from monthly royalty checks that turn out to be smaller than expected. (Chesapeake Energy and Anadarko Petroleum are currently being sued by the Pennsylvania Attorney General for allegedly withholding royalties from their lessors in Bradford County.) Then, when the well had run dry after a few years, those checks would diminish and sometimes even become bills to reimburse the drilling company for losses on the well.

“When you’re talking about inheritance of mineral rights, you can inherit an asset that may soon turn into a liability,” says Doug Shields, an anti-fracking activist with Food & Water Watch in Pittsburgh.

As Shields explains, the vast majority of leases are assigned effectively in perpetuity. In his words: “If you sever rights to what’s beneath your feet, shame on you … ‘cause now you’ve got a partner for the rest of your life.”

Please! Pause! And prepare yourself for a thing you’ve probably never thought about, once, but could meaningfully prevent some fossil fuel extraction.

So you and your co-lessors have decided that selling your rights isn’t worth the environmental and financial risks, and, in fact, you’d like to donate them to an environmental organization. Admittedly, it’s pretty complicated.

If the owner of, say, a forest or a piece of pastoral farmland wants to protect that land, they can enter into something called a conservation easement with a land trust. The land owner donates or sells the development rights to their property to a land trust or other conservation organization, and can get a tax deduction in return. The forest stays Bambi-esque, the farmland stays Babe-ly. As in, the movie about the pig.

But that might not actually protect whatever is underneath the farm or the forest. There’s no children’s movie about the pristine bucolia of fossil fuel reserves, unfortunately, and there’s also currently little legal means to keep them intact.

Brent Bailey, executive director of the West Virginia Land Trust, says his organization has been offered donations of mineral rights before. It’s relatively untested territory, though, and there are currently no financial rewards in the tax code for donating mineral rights. However! A 2017 study from Stanford proposed incorporating something called “mineral estate conservation easements” or MECEs into state property tax law.

An MECE is a means to conserve gas or oil or coal reserves as you would a very beautiful or ecologically important piece of land by donating an “easement” on mineral rights to a land trust. Essentially, it’s a legal mechanism that could prevent fossil fuels from being drilled or mined, a tiny bit at a time. But as a practice, MECEs are in extremely nascent stages, and would have to be amended into state tax codes.

Tax codes! Estates! In the age of rampant EPA deregulation, this is the sexy stuff of actual climate resistance. And the thing about highly specific and extremely boring pieces of legislation (i.e., amendments to the tax code!!!) is that they’re often the easiest ones to petition your local congressperson about. They’re definitely not hearing about those issues frequently and they’re not — yet, at least — heavily politicized.

Back to you, question-sender. Pal. You inherited a potential headache, but you have the power to transform it into a really worthy mission. If you want to change the extremely sexy landscape of tax law in a way that could actually be a significant form of climate change activism, this is your issue, baby. Mineral estate conservation easements. Say it a couple times, slowly. Breathe it in — accept it into your core. You didn’t ask for it, but this is your calling for 2018.