When Beth Terry saw a photo of an albatross with a rib cage full of trash, she decided to give up plastic. Today, Terry might just be the world’s foremost expert on how to live without the stuff. And that’s no easy task. Think about all the nooks and crannies of our lives that plastic has made its way into: food packaging, clothing, the protective box your favorite gadgets come in, even facial scrubs. And while there are all kinds of reasons to hate plastic, for Beth Terry, it’s an issue of justice. “The more I learn about plastic, the more I realize that it’s those most vulnerable on the planet — whether it’s animals or babies or poor people — who are affected the most,” she says.

When Beth Terry saw a photo of an albatross with a rib cage full of trash, she decided to give up plastic. Today, Terry might just be the world’s foremost expert on how to live without the stuff. And that’s no easy task. Think about all the nooks and crannies of our lives that plastic has made its way into: food packaging, clothing, the protective box your favorite gadgets come in, even facial scrubs. And while there are all kinds of reasons to hate plastic, for Beth Terry, it’s an issue of justice. “The more I learn about plastic, the more I realize that it’s those most vulnerable on the planet — whether it’s animals or babies or poor people — who are affected the most,” she says.

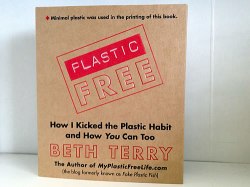

Terry’s new book Plastic Free: How I Kicked the Plastic Habit and How You Can Too is published without plastic, all the way down to the glue. (If you’re going to shop for it online, check out her website first to learn about buying from a place that has committed to shipping it without plastic.) We talked with Terry recently about plastic-free living, why the proposed alternatives to bisphenol A (BPA) might be worse, and the connection between cutting out plastic and building a local economy.

Q. Why did you write this book? Whom are you trying to reach?

Q. Why did you write this book? Whom are you trying to reach?

A. While I was writing, I was thinking: What would have helped me when I didn’t know anything? I tried to make this a book for people who are just starting [to cut out plastic], or who are already on their way.

I’ve been working on going plastic-free for five years. I did it slowly. I really recommend that people take it step by step, and then it won’t take so much time. Because a lot of the time and effort is just developing a new habit. Once you have the habit, you don’t have to think about it. For example, I never leave the house without a reusable bag anymore — and I don’t have a car, so it’s not a matter of leaving a bag in the car. It’s not hard, it was just learning to remember to do that in the beginning.

Q. Have you calculated how much money you save with your new habits, like buying food in bulk?

A. I went from eating Stouffer’s mac-n-cheese in a microwavable plastic tray to eating food from the bulk bins, so it’s kind of hard for me to compare. But to me, now, what I put in my body is more important than having lots of stuff. So I’ve shifted my spending.

Q. Where are the places you’ve been most surprised to find plastic?

A. I still think that the most surprising thing I ever discovered is that chewing gum is made out of plastic. And that there’s plastic in a lot of pills — especially time-release pills and capsules.

So it’s the plastics that are meant to be ingested that surprise me. And you have to be careful. People say to me, “It’s okay because I chew Glee Gum, and Glee is made with natural chicle.” And that’s true, it’s made from natural chicle — mixed with plastic. I discovered a plastic-free chewing gum this year that’s made by an English company, Peppersmith.

Q. BPA gets a lot of attention. What else should we be aware of, when it comes to human health?

A. There are thousands of additives that could be added to any particular plastic product; they affect the strength, flexibility, color, and even sometimes add antimicrobial and flame-retardant properties. When you see the number in the triangle at the bottom of a container, that tells you what the basic polymer is. Those basic plastic molecules are strung together, but the additives aren’t really attached, and when the plastic is subjected to stress, like heat or light or age, those additives can leach out. Plastics manufacturers are not required to disclose any of the ingredients in their formulations, so we don’t know what chemicals have been added.

In one experiment in Canada some researchers were using plastic polypropylene test tubes — #5 plastic, which is considered to be food-safe. Their experiment had nothing to do with plastic, they just happened to be using plastic test tubes, and their results kept getting contaminated. What they found was that additives in the tubes were leaching into the chemicals they were actually testing. They were shocked about this because they thought #5 plastic was nonreactive — everyone thought that. A lot of food containers are made out of #5 plastic and the FDA labels them as food-safe.

The point is that if we don’t know what chemicals have been added, there’s no way for us to know what could be leaching out and whether it’s safe or not.

The alternatives to BPA being developed — we really don’t know if those alternatives are any safer than BPA itself. They haven’t really been tested either. PVC, which is full of pthalates, is one “alternative” to BPA. And there’s some suggestion that bisphenol S (BPS), a BPA alternative, might have even more estrogenic activity. I don’t know if that will turn out to be true, but these alternatives need to be tested more.

We just have to be careful. We have to ask questions: What are you using instead of BPA? Campbell’s has said they’re going to phase out BPA from their cans, but they won’t say what they’re going to line them with instead. So Healthy Child Healthy World has a campaign going to get Campbell’s to reveal what the alternative will be.

Q. In your book, you highlight a few companies that keep sustainability at the core of their business model, rather than just, say, promote reusable bags. But they’re all small, local businesses. Is that a coincidence, or do you think there’s a way for those models to be scaled up?

A. The Texas-based company in.gredients wants to get the plastic out of the entire supply chain, and they say the only way to do that is to keep it local. They have their local vendors picking up their empty container as they’re delivering food in a new container. You can’t do that in a scaled-up business.

Plastic enables the food system to be monstrous. If we reduce our food miles, we don’t need as much plastic. It boils down to that. If you increase your food miles, then you have to find more ways to preserve the food because it has to last longer.

We have a company [in the Bay Area] that sells yogurt in returnable mason jars and ceramic containers. You pay a deposit and get it back when you return the container. That only works locally. A company like Stonyfield Farm, which is national, can’t do something like that, or they haven’t figured out a way to make it work.

And the problem with yogurt is that most is packaged in plastic while it’s hot. They pour the hot milk into the plastic container, put the bacteria in and seal it up, and the yogurt [culture] is basically formed in the plastic container. And we know that plastic leaches more when it’s subjected to high heat. There’s a company here, Straus, that sells yogurt in plastic containers, but their yogurt is vat-set. They don’t put the yogurt into the cups until it’s cooled down, specifically because of the leaching plastic. But that can’t really be scaled up — the reason companies fill the containers hot is they can do it so much faster.

Q. Do you have a favorite tip or recipe that you’ve discovered in your plastic-free life?

A. The one thing that I enjoy the most is homemade chocolate syrup. It takes the place of Hershey’s syrup in the squeeze bottle. It tastes way better, it’s super easy to make, and it’s all from sugar and cocoa powder from the bulk bin, salt from a box or bulk bin, water from the tap, and vanilla from a glass jar. The glass bottle has a little plastic cap on it, but that’s the only plastic involved. The recipe is in the book.

Q. You’ve figured out how to make a lot of things from scratch. Does that take up a lot of time?

A. I don’t do all of them on a regular basis, though I have done them to see if they work. There are things I just do without, but I wanted to present them as options in the book. Like if you want to have mayonnaise on a regular basis, it’s easy to make. If I cared about mayonnaise as much as I care about chocolate syrup, then I would make it!

I actually don’t spend a ton of time being Suzie Homemaker, but I do spend a lot of time researching and experimenting. It’s my passion — and it’s my way of giving back to the world because I share all the information I discover.

Q. If you weren’t so busy with book touring and promotion right now, what would you be doing?

A. What I would love to work on is a campaign to get Trader Joe’s to stop packaging their produce in so much plastic. They’re worse than any other grocery store I’ve seen, and Trader Joe’s caters to a clientele that cares about the environment. So to wrap all their produce in plastic is just hypocritical. That was why I went after Brita, too, because Brita was advertising itself as an environmentally friendly alternative to bottled water. And yet, even though there actually was a way to recycle the filters [in Europe], they weren’t doing it in the U.S. I guess hypocrisy just really bugs the crap out of me.