It�

It’s been more than 350 years since the Rappahannock Tribe was forcibly removed from its ancestral lands on the Chesapeake Bay in present-day Virginia. Now, it’s finally getting some of its land back.

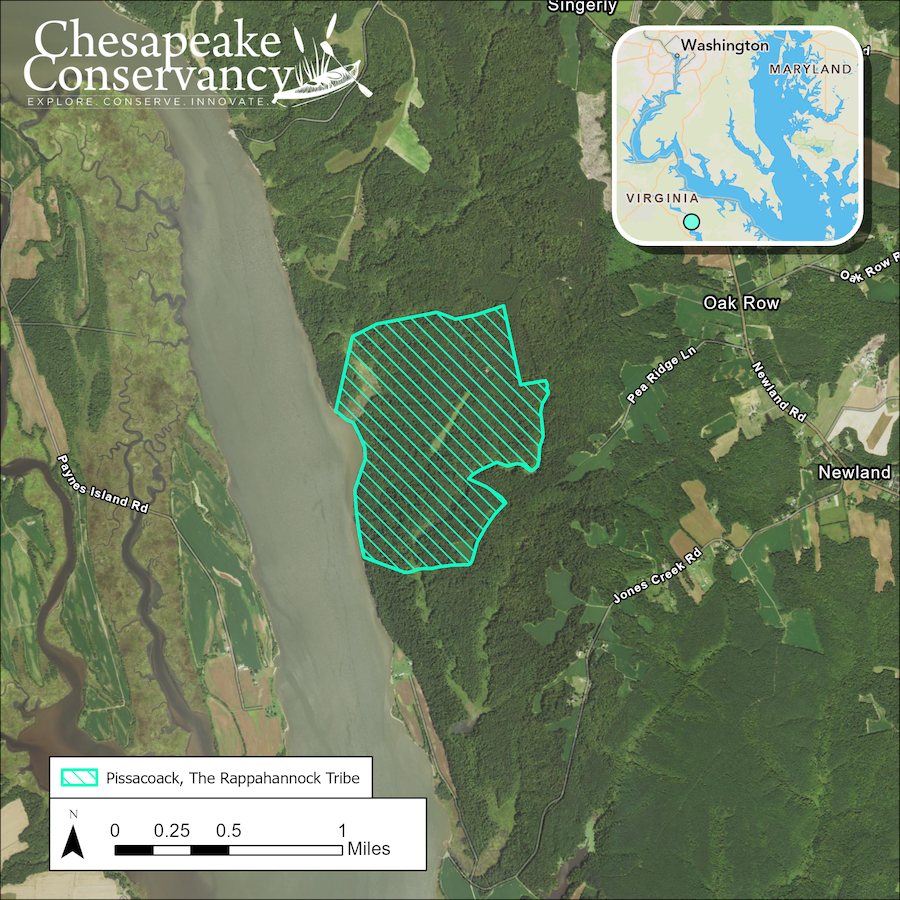

Rappahannock Tribe members were joined by conservation leaders and U.S. officials — including Interior Secretary Deb Haaland — on Friday to commemorate the return of a 465-acre parcel of land that was seized by European settlers in the 17th century. The return of the land, which has been restored to its original name of Pissacoack, is “a historic victory for conservation and racial justice,” the tribe said in a statement.

The news marks the culmination of a yearslong collaboration between conservationists and tribal members to protect the area and restore it to its original owners. Besides its reputation as one of the Chesapeake Bay’s most beautiful places, the region’s bluffs and wetlands provide important habitat for fish and migratory bird species — some of which have cultural and religious significance to the Rappahannock. Bald eagles, for example, descend upon the area by the hundreds each year as part of their annual migrations.

“You can sometimes see 40 eagles in the span of a couple hours,” said Joel Dunn, president and CEO of the nonprofit Chesapeake Conservancy.

Dunn’s organization helped lead efforts to restore Rapphannock ownership of the land following multiple threats that it would be developed into residential subdivisions or a sprawling resort complex with an 18-hole golf course. The organization and its allies in the tribe feared development would decimate wildlife habitat and irreparably harm the land.

“The river is life to us,” said Anne Richardson, chief of the Rappahannock Tribe. She described the resplendent landscape as the tribe’s “grocery store” — home to some 250 or more species of plants and animals that the tribe gathers to eat or use for craft and medicinal purposes. Some of these species have long served as staples for the tribe — including the blueback herring, whose populations have fallen dramatically due to urbanization and agriculture. Richardson said it has been painful to watch their decline. “It’s difficult to lose those things,” she said.

Thanks to a massive fundraising effort that included donations from a wealthy family and a grant from the nonprofit National Fish and Wildlife Foundation sponsored by Walmart, by February 2022 the Chesapeake Conservancy had collected enough money to buy a 465-acre tract of land and donate it to the Rappahannock Tribe. As part of the deal, the land was placed into a conservation easement with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The Rappahannock Tribe, which will manage the land, now intends to place the land in trust with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which will give it additional protections and make the tribe eligible for federal conservation funding.

Dunn said he hopes the land transfer will inspire more conservation partnerships across the country. “I really hope this becomes a model,” he said, “to share the challenge we have to protect our environment for current and future generations.” Indeed, the last few years have seen growing success for the landback movement, which seeks to restore stolen land to Indigenous ownership. Tribes from the Esselen near Big Sur, California, to the Passamaquoddy on Pine Island in Maine have regained millions of acres through land purchases, donations, and legal victories.

On the Chesapeake Bay, Richardson said the restoration of the Rappahannock Tribe’s land would heal her people and the natural world. “To help preserve and restore everything that’s been depleted — that’s my goal,” she said.

The tribe is planning to develop an Indigenous conservation education center on the river, where students and the public can learn about the tribe’s history and ecological knowledge. “Hopefully we can transform the children and young people who will become our senators into leaders in conservation,” Richardson said. “We have valuable things to teach this society at a time when our planet is in crisis.”