If you’re traveling through the suburbs around Niagara Falls, you might notice that one of them is missing. There are still roads, and you see empty driveways and old sidewalks hiding in the grass. But no one lives here anymore.

There aren’t any signs saying where you are, so I’ll tell you: It’s Love Canal, an idyllic suburb that caught the country’s attention back in 1978 when its residents realized that they were living on a toxic-waste landfill. Love Canal’s residents organized, protested, and kept their story in the media for a year. Along the way, they helped launch the modern environmental movement.

A new history of that struggle, Love Canal: A Toxic History from Colonial Times to the Present by the environmental historian Richard S. Newman, reveals details that I’d never heard before. Love Canal’s evocative name? The land used to be owned by William T. Love, a real-estate dreamer of the 1890s who dug the canal in the hopes of creating a model city along its banks. Love imagined his city would be powered by hydroelectric energy poached from Niagara Falls. In contrast to the dirty, coal-powered factory towns then powering the American industrial revolution, Love’s city would boast such luxuries as clean drinking water, lines for telephone, gas, and water, as well as mail delivered by pneumatic tubes.

In 1894, local papers reported that the excavators hired by Love “have already made quite a hole and a big pile of dirt,” but that was as far as the model city ever got. Love lost a ton of money, then quit and moved west. Local kids used the canal as a swimming hole in the summer and an ice pond in the winter, until a local producer of bleaching powder, rubber, and explosives noticed it.

From 1942 through the early 1950s, that company, Hooker Electrochemical, filled in the unfinished canal with 22,000 tons of toxic waste, much of it leftover from Hooker’s work outfitting the military for World War II.

In 1952, the Niagara Falls school board approached Hooker and asked if the company would be willing to part with the land so that it could build a suburb and a new elementary school on it. Several Hooker company officials objected. Maybe the land was safe for a park, they said, but not housing. Still, in April 1953, Hooker sold the former canal to the school board for $1. The deed of sale mentioned that the site was brimming with chemical waste, and that, by signing the deed, Niagara Falls assumed all liability for any problems.

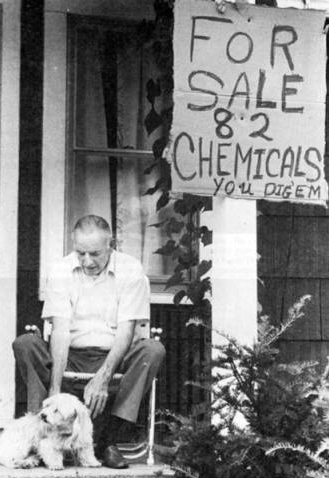

When the school board then sold the land to a housing developer in 1957, Hooker executives warned city officials against putting houses on the site. “There are dangerous chemicals buried there in drums, in loose form, in solids and liquids,” A.W. Chambers, a Hooker representative, told the Niagara Falls Gazette. All they could do was warn, though — Love Canal was no longer Hooker’s property. The developers built hundreds of houses atop the landfill anyway.

To the thousands of people who moved in during the 1960s and 1970s, Love Canal was a nice neighborhood — working-class and friendly. But weird things happened. When the kids threw rocks against the pavement they exploded like firecrackers. Manhole covers launched themselves into the air without warning. Kids playing baseball would get strange, chemical burn-like rashes when they slid across the grass. Dogs went bald.

Neighbors shared stories and slowly realized they had more than their share of miscarriages, birth defects, and cancer. In 1976, New York State health officials started testing the area around Love Canal for dangerous chemicals. The following year, a regional officer for the newly formed Environmental Protection Agency wrote a letter to his bosses in Washington, warning that the area around the canal was so polluted that the state’s only option was to buy up the 40 or 50 homes closest to the canal and tear them down. Local officials panicked, and asked for more tests.

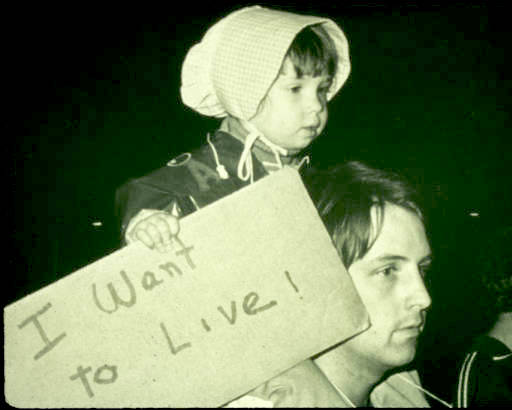

More tests just made everything scarier: 82 different chemical compounds were found around Love Canal. They were sitting in puddles, hiding in sump pumps, and seeping through basement walls. Many, like benzene, were known carcinogens. State health officials found that women in the neighborhood miscarried at 1.5 times the level of the general population. Some 13 percent of the babies born in one section of houses near the canal had birth defects. The state health commissioner advised evacuating all pregnant women and children under the age of 2.

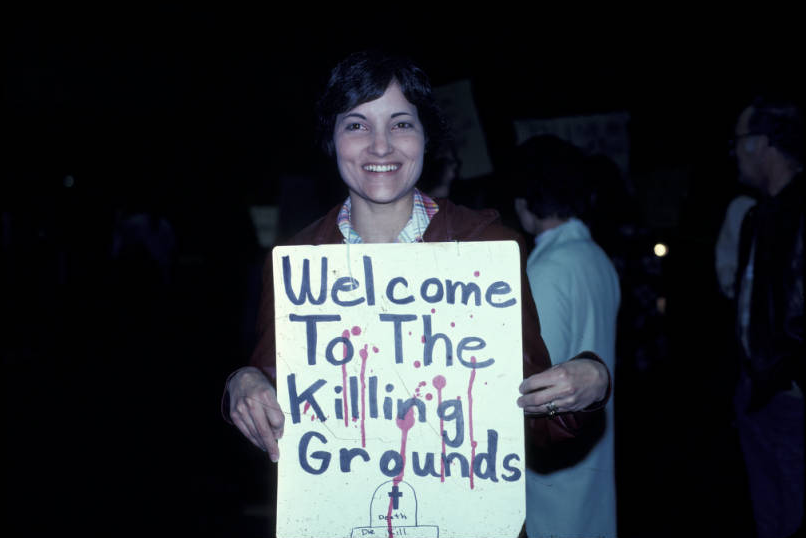

After years of rumors and unsettling data, news of the planned evacuation made the people of Love Canal go from afraid to ballistic. They began organizing protest groups, the most visible of which was the Love Canal Homeowners Association (LCHA) led by a local housewife named Lois Gibbs. Another organization, the Concerned Love Canal Renters Association (CLCRA) is less well-remembered. It was run by a community activist named Elene Thornton, and consisted mostly of African American residents from a nearby federal housing project. Television crews and reporters, enchanted with the idea of white housewives turned activists, largely wrote the CLCRA out of their coverage of Love Canal.

What’s also forgotten is just how vicious the situation was. At one point, residents burned effigies of Jimmy, Rosalynn, and Amy Carter (who was 10 years old at the time).

But it was Carter’s executive decisions that paid for people to move from Love Canal. In 1978, Carter approved emergency federal aid so that New York State could start buying the homes of the 236 families closest to the canal.

That didn’t appease the other 710 families that still had to live there. In May of 1980, the EPA announced that blood tests of 36 Love Canal residents revealed nearly a third “exhibited chromosome damage of an abnormal nature.” The LCHA responded by holding two EPA representatives hostage. When the police arrived, they found the entrance to the LCHA offices blocked by hundreds of angry suburbanites armed with two-by-fours. Gibbs called the press, and the White House. “We’ll keep them fed, we’ll keep them happy,” she said of her hostages.

The homeowners association released their hostages after five hours. Gibbs later recalled that one of them, Frank Nepal, was kind of into it. “He was telling us how he used to be involved in the Vietnam War protests,” Gibbs said. “So he thought it was kind of cool, being held hostage.”

New York and the federal government squabbled over buying out the remaining 710 families. A compromise was finally reached in October of 1980, with the federal government providing $7.5 million in grants and another $7.5 million in loans to the state so that it could begin buying homes immediately. The following spring, Love Canal was a ghost town.

The Love Canal experience also led Carter to create the Superfund program in 1980. That way, when another Love Canal happened (and there would be many drums of toxic waste unearthed in the following decades), there would be funds ready to pay for any cleanup and relocation.

Time has edited the story of Love Canal. The EPA rescinded the chromosome study in 1983, saying that it was poorly done. Gibbs’s two children, both sickly as children, grew up to be healthy adults. A long-term study carried out by the New York State Health Department found the health of former residents wasn’t that different from those of others living in Niagara County and throughout the state. Sure, they died more frequently of heart attacks, car crashes, suicide, and bladder and kidney cancer, but overall, their mortality rates fell within the average range for the area.

Former Love Canal residents continue to dispute this research. For one thing, residents who died of cancer before 1972, or moved away before 1978, were not counted in the state’s study. For another, why compare the health of Love Canal residents to another group that lived nearby? Why not make the control group people who lived in a community with no pollution at all?

The toxic waste filling Love Canal proved too big to move, so the canal was covered in clay and entombed instead. Or, as Gibbs said, it lived in “a gated community for chemicals.”

In the 1990s, some 200 homes at the outer edge of the evacuation zone were refurbished and renamed Black Creek Village. A few years later, residents of Black Creek Village began complaining of miscarriages and mysterious rashes. Not possible, replied an EPA spokesperson. The area around Love Canal was surrounded by monitoring wells and “the most sampled piece of property on the planet.” Any leak in the landfill would be detected. Because it’s so closely watched, the story goes, what was once the most dangerous suburb in America is today one of the safest.