This story was originally published by CityLab and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

More than 43,000 lots in Philadelphia sit vacant, many invaded with overgrown weeds and strewn with trash. As CityLab has previously reported, this is as much a public health problem as it is an economic one. Walking past such a site, researchers have previously found, can make your heartbeat just a little faster, indicating increased levels of stress. And it’s no wonder: Studies have also shown that urban blight tends to attract crime and gun violence.

It’s all taking a toll on the mental health of residents in vacancy-hit neighborhoods. “People felt that [the vacancies and abandonment] fractured ties between neighbors, [affecting] the social milieu of the neighborhood,” says Eugenia South, a senior fellow at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine who’s been studying the health effects of urban blight in Philadelphia. People also told her that they “felt stigmatized, neglected by the government,” as well as experiencing “depression, anxiety, stress, and fear.”

While the city scrambles to sell the lots for redevelopment, the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society has been working with residents to turn some into parks and community gardens. Now a new study in the Journal of the American Medical Association from South and her colleagues points to evidence that their efforts are, in fact, having a positive effect on residents’ well-being. In particular, turning lots into green spaces alleviated the feeling of depression among residents who live in the poorest neighborhoods the researchers studied.

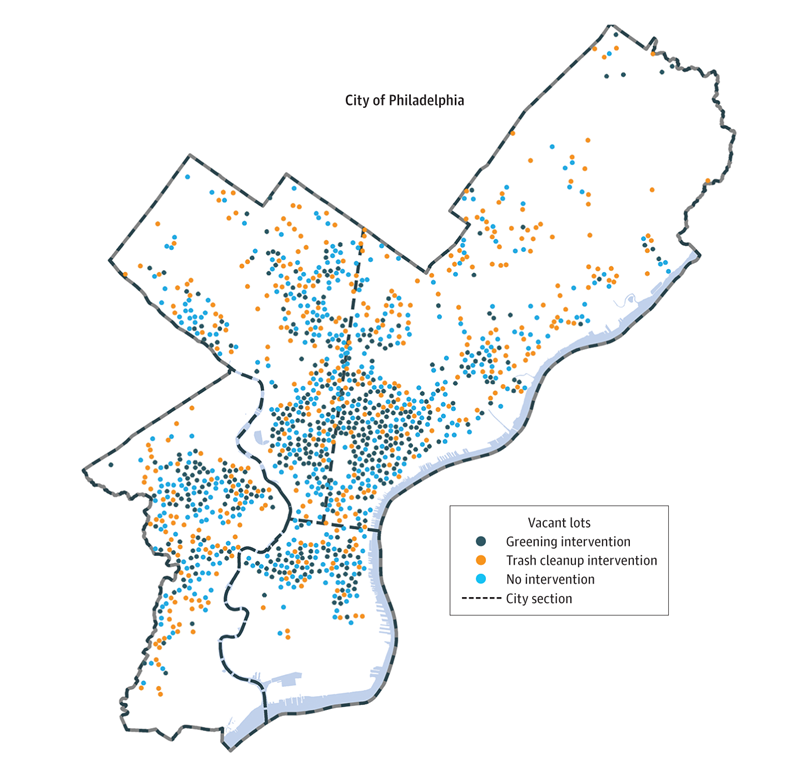

Some lots got the “gold standard” intervention, while others either got a basic cleanup or no intervention. (JAMA Open Network)

The researchers randomly chose 541 lots around Philadelphia and divided them into three groups. Working with the horticultural society over a two-month period in the spring of 2013, the researchers gave one group the greening intervention — what South calls the “gold standard” — in which they graded the land and planted grass and trees. Lots in this group also had low fences installed, which researchers hypothesize increase the beneficial effect by delineating the spaces as being taken care of but not acting as barriers. In another group of lots, they only cleaned up trash and debris and mowed the grass. The third — the control group — received no treatment.

A total of 347 randomly chosen residents living near those lots were surveyed 18 months before the intervention and 18 months after, and asked to rate how often they felt things like anxiety, hopelessness, worthlessness, and depression — based on a tool for screening the prevalence of serious mental illness in a community. None were told the survey had anything to do with the revitalization of vacant lots.

What they found was that in neighborhoods below the poverty line, greening interventions decreased residents’ feelings of depression by more than 68 percent. Meanwhile, residents near lots that only had trash removed saw little improvement. That difference, according to South, strengthened the researchers’ confidence in their findings.

“We wanted to make sure that if we see a difference in the greening group, is it because people were going into the neighborhoods, showing interest and investing in them, or does it actually have to do with green space?” said South.

Lots in Philadelphia were randomly assigned three interventions to strengthen confidence in the findings. (JAMA Open Network)

The study’s finding is in line with what researchers have observed in the past — that strolling through the woods led to more positive emotions, for example, and that Londoners living near trees were prescribed fewer antidepressants. One explanation is that green spaces help us recover from mental fatigue.

“We have a lot of mental input throughout they day, and this is particularly true in urban environments,” said South. “And there is something about the green space itself that allows you to disconnect, to be present without a lot of stimuli coming in.” Green space also allows residents to build relationships with one another, she added, and helps people cope with daily stress.

What does that mean for U.S. cities? South cautioned that the greening intervention is not the “be all and end all” to America’s mental-heath troubles, for which treatment often comes at a premium beyond what low-income families can afford. At the same time, she argued, this wouldn’t be just a Band-Aid project. Rather, it can be an intervention with lasting effect that a city government — or even community groups — can implement in targeted neighborhoods for as little as $1,600 per lot, plus $180 a month for maintenance.

But the lots do have to be maintained, South stressed. And there has to be some kind of infrastructure that allows individuals who want to do this on their own to do so, whether that’s providing financial help or material and supplies.

The study has its limitations, in that the researchers weren’t able to measure the long-term impacts, or exactly how residents interacted with the spaces. South also hopes to study what she describes as the “doses” of green space needed for optimal impact. “So, thinking about green space as a drug, we don’t know how often you’d have to spend time in a green space and for how long,” she said.

But she and her colleagues are sure of one thing — that there is a benefit just to putting in a green space. “We can start to say that there is causation here,” South said. “We rarely say anything so definitively — ever — based on one study, but the strength is [in] the design of the trial.”