Before May 17, 1954, there was a public and legal understanding that black kids could go to exclusively “black schools” with black teachers, and that their learning experience would be equal to that of the exclusively “white schools” they were forbidden to attend. But on that day, the U.S. Supreme Court came to a different understanding in the Brown v. Board of Education case. A bunch of badass lawyers led by the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (NAACP LDF) convinced the justices that racially segregated schools are both innately unequal and also lead to unequal outcomes that will almost always benefit white Americans while disadvantaging black Americans.

Sixty years later, we’re still finding racially segregated schools with unequal outcomes. This is probably because we’re not dealing with the root cause of the inequality. That root was identified by the psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark whose “doll tests” of the 1940s convinced the Supreme Court justices in Brown v. Board that segregation affects African Americans’ “hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone.” The Clarks were happy that their studies were used to undo segregation, but they were perturbed that the ruling did not address the two issues that were central to their findings: That racism is inherent to American institutions, and that school segregation also inhibited white children’s growth and development.

When looking at segregation today through the lens of environmental justice, we see that racism is still inherent. However, contrary to Clark’s other unused finding, it’s children of color whose development is most inhibited, in terms of their exposure to toxic pollution and the accompanying health risks.

[grist-related tag=”polluted-schools” limit=”20″]

Take California, where over a half-million students attend schools that sit within a quarter-mile of areas like farms where highly hazardous pesticides are sprayed, according to a new report from the statewide coalition Californians for Pesticide Reform (CPR) and data from the state’s public health department. About 118,000 of those attend schools near the heaviest application of toxic pesticides. Here’s where the separate but unequal comes in: Latino students are 91 percent more likely than white students to attend schools with maximum exposure to these poisonous sprays.

Many of these pesticides are composed of the kinds of injurious ingredients that contribute to academic problems. “Some of the pesticides used near California schools have been linked to deficits in cognitive skills, such as learning and memory, and in social skills, similar to those seen in autism spectrum disorder, based on studies in young children,” Irva Hertz-Picciotto, deputy director of the UC Davis Children’s Center for Environmental Health, said in the CPR report. “It should also be noted that children spend about half of their waking hours at school, suggesting that these exposures may be as important as the pesticide products used in and around the home.”

“Even in very small amounts, pesticides can have profound impacts on children’s health and intelligence,” said Margaret Reeves, senior scientist at Pesticide Action Network in a follow-up report on the pesticide data. “Nearly 10,000 pounds of neurotoxic chlorpyrifos are used in close proximity to California schools. The pesticide is linked to falling IQs, increased risk of ADHD, and other developmental disorders.”

Reeves analyzed state data to locate the 10 schools where the largest amount of the most venomous pesticides were applied close by. Many of those schools have predominantly Latino students. California is largely a Latino state, but Reeves’ analysis shows that these racial disparities are a problem even in counties where whites are the majority, suggesting that segregation is a culprit.

Take for example Ventura County, one of the wealthiest counties in the nation, and almost 85 percent white in a state that is about to become only the second in the nation where whites are not the majority. But zoom into the city of Oxnard, where farmworker rights activist Cesar Chavez lived as a child, and you’ll find a city that’s around 73 percent Latino and a much lower median household income compared to the county.

In Oxnard, you’ll find Rio Mesa High School, the school where Reeves found the largest concentration of pesticides have been applied within a quarter-mile of students — 28,975 pounds of the stuff. Rio del Valle Jr. High School is also found here, with its 82 percent Latino students — and its total school populace eligible for free or reduced lunch, and get around 18,000 pounds of pesticides with those lunch tickets. Add in the Oxnard schools Providence High and Rio Rosales Elementary School and you have over 21,000 students — mostly Latino and Filipino — exposed to over 80,000 pounds of toxic pesticides sprayed close to where they are sent to learn.

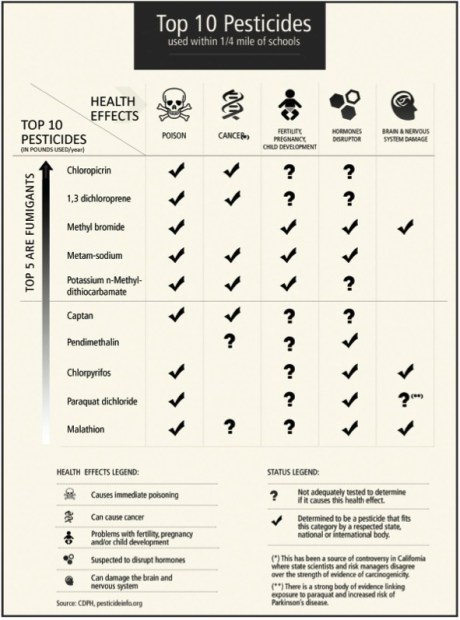

These children are most at risk (compared to their peers around the state) to fumigants, the most heavily used pesticide in California. The EPA rates fumigants “highly acutely toxic” — the movie rating equivalent of XXX You Might Even Die While Watching This. Some versions of it cause cancer while others cause respiratory and reproductive problems. Simple exposure can lead to cognitive function and physical coordination disorders. Here’s a chart from the CPR report that puts all this into perspective:

Californians for Pesticide Reform

So while Ventura County is getting most of the fumigants, it’s specifically the schools that Latino kids attend that get the most exposure. In the 15 counties identified in the CPR report for having the most pesticide exposure, Latino students were 46 percent more likely than white students to attend schools that sit too close to pesticide use for learning comfort.

Advocates for protecting children’s health are asking for buffer zones that keep pesticide operations far, far from education centers. One of the main problems is pesticide drift — because like politicians, pest sprays don’t always hit their target; and, more often they carry whichever way the wind blows. Advocates are also asking that companies use safer alternatives to fumigants, with ingredients that don’t cause cognitive dysfunction in students.

The racial inequities are nothing new to Latino Californians. Scientists such as Rachel Morello-Frosch, Manuel Pastor, and Bill Jesdale have found similar disparities for health risks due to all kinds of pollution exposures up and down California for years. In 2005, Morello-Frosch and Jesdale released the study “Separate and Unequal: Residential Segregation and Estimated Cancer Risks Associated with Ambient Air Toxics in U.S. Metropolitan Areas,” where they concluded that “disparities in exposures to cancer risks associated with ambient air toxics are affected by the degree of racial residential segregation, and that these exposures may have environmental health significance for populations across racial/ethnic lines.”

A civil rights complaint filed against EPA in 2001 led to the agency admitting 10 years later that Latino schoolchildren were unfairly overexposed to methyl bromide — the kind of pesticide fumigant that leads to cognitive function disorders. Those fumigants are still applied today disproportionately by Latino students according to the Center on Race, Poverty and the Environment, which helped file the complaint and is still seeking justice.

This is what current NAACP LDF President Sherrilyn Ifill was talking about when she wrote recently that 60 years after the Brown v. Board ruling, “the quality of a school remains largely dependent on its students’ race and socioeconomic status. Because the problems in our nation’s schools are integrally affected by race and class, we won’t solve our education crisis without solutions that are race- and class-conscious.”

Until we find those solutions, the impacts of segregation will not only affect the hearts and minds of students, but also — to amend the Brown v. Board ruling — the lungs, wombs, and lives of Latinos in ways that will be tough to undo. If the Clarks were alive today, they would probably remain upset that America still hasn’t dealt with the root problems inherent in its institutions — the racism that keeps these disparities alive.