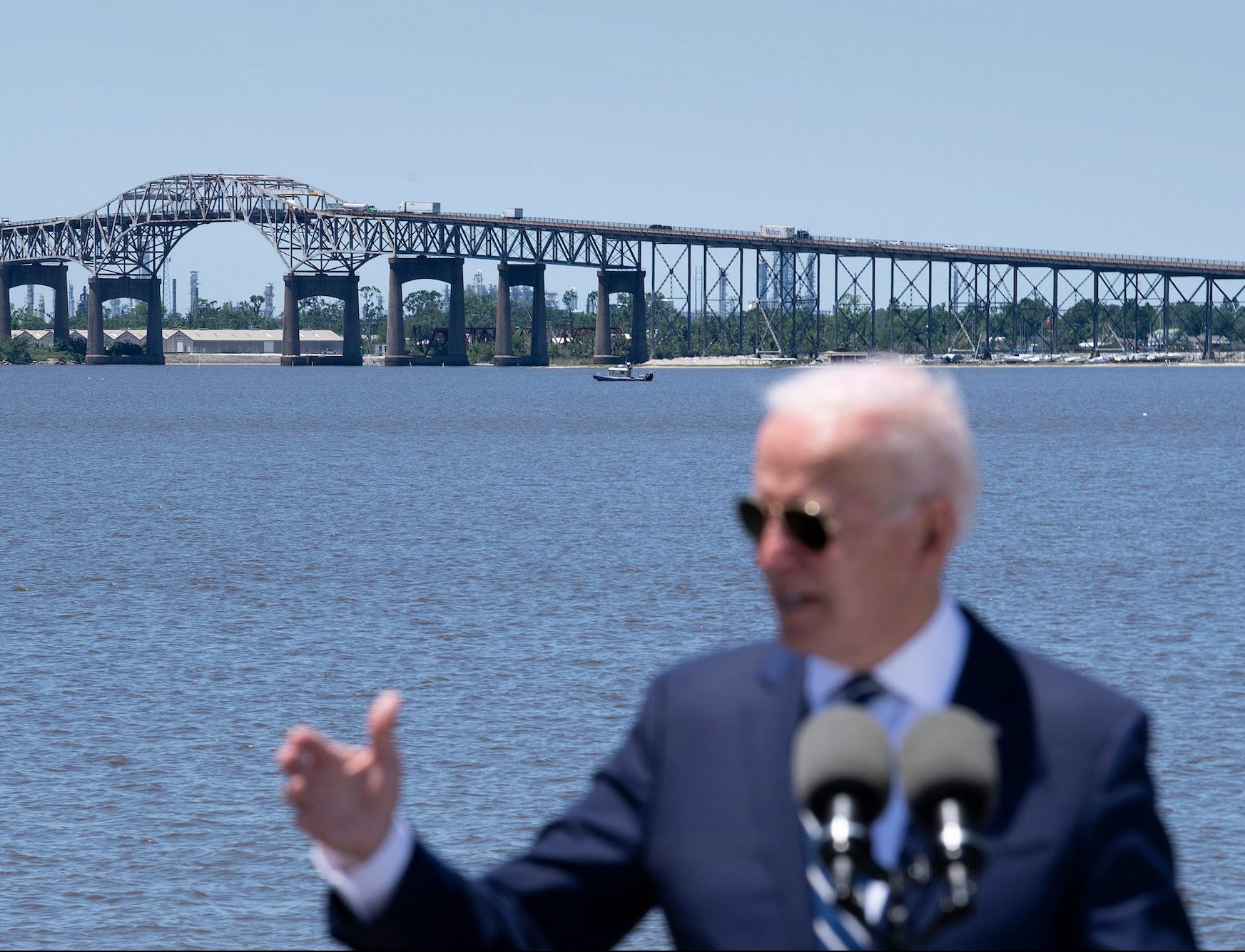

When President Joe Biden unveiled his $2.25 trillion “American Jobs Plan” in early April, many climate activists breathed a (small) sigh of relief. Although the plan was smaller than the $10 trillion progressive Democrats had proposed spending on revamping the country’s infrastructure, it was, in many ways, a Green New Deal in miniature. It included huge spending on clean energy, a civilian jobs program known as the “climate corps,” and a push to get electric cars on the road all across America. It was without question Biden’s primary plan to cut carbon emissions. The only one. The big one.

Now, however, there is rising concern that the “big one” may not be so big after all. Key features of the bill — like a requirement to produce electricity from clean sources, or hundreds of billions of dollars in support for electric vehicles — are in contention as Republicans and Democrats tussle over the price tag. And without them, the country’s chance of cutting carbon emissions 50 percent by 2030 — as Biden recently promised at his international climate summit — is basically zero.

“We need the full American Jobs Plan,” said Lena Moffitt, campaigns director at Evergreen Action, a climate-focused policy group.

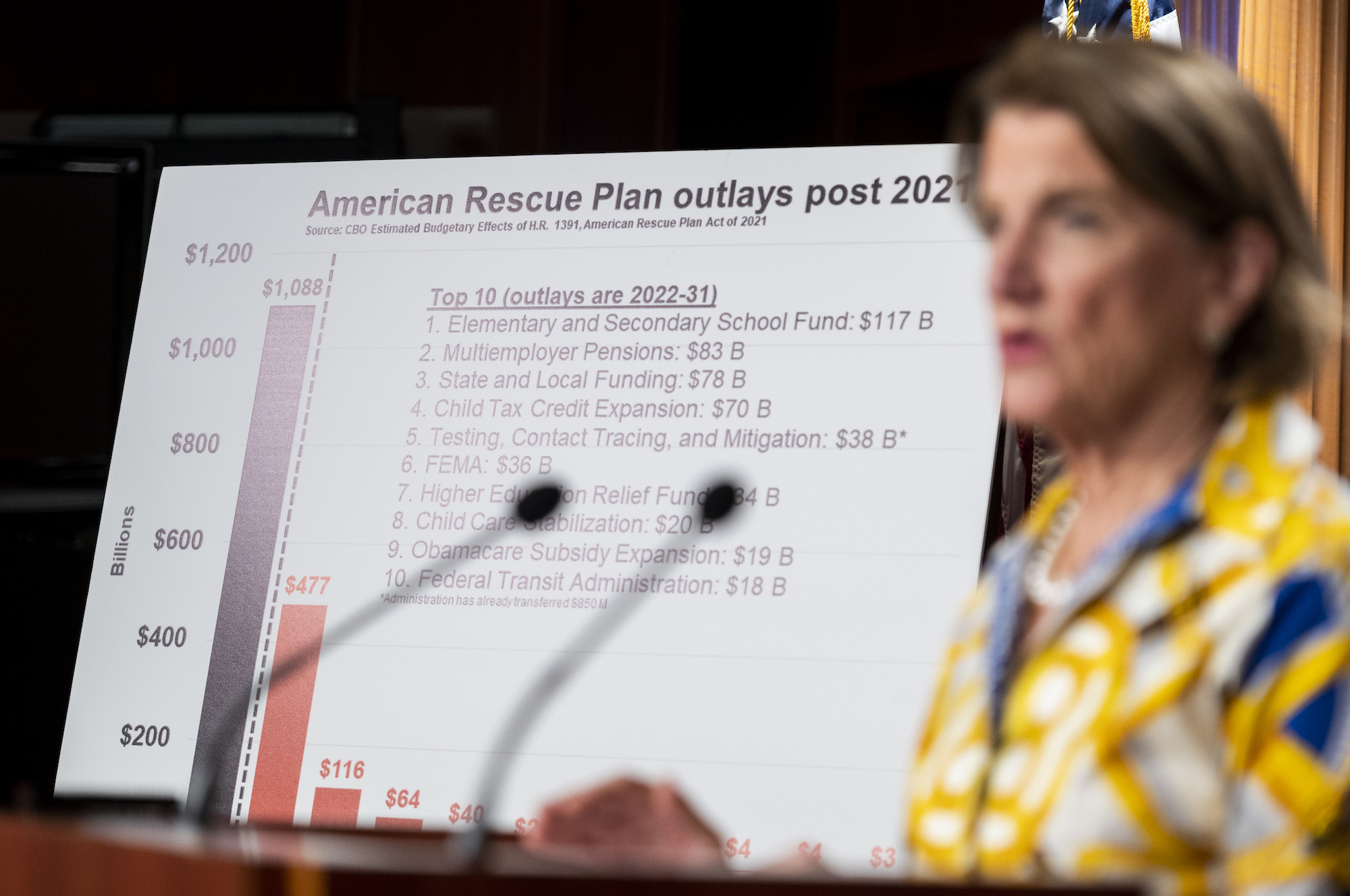

Over the past couple of weeks, progressives and climate activists have watched with dismay as the Biden administration and key Democratic leaders have engaged in a protracted back-and-forth with Congressional Republicans. Biden’s original plan was for $2.25 trillion in spending; after negotiations, he slimmed it down to $1.7 trillion. (A lot of money, but still probably not enough to address the 6.5 billion metric tons of CO2 emissions the U.S. spews into the atmosphere every year.) Republicans came back with a counteroffer that they claimed included $928 billion in funding for highways, roads, and public transit; Democrats, frustrated, protested that only about a quarter of that would be actual new spending.

If this all seems like a lot of hullabaloo over numbers, it is … and isn’t. The result of these negotiations — layered though they are in political posturing — might very well determine whether the U.S. can come even close to Biden’s carbon-cutting target. The U.S. Congress has not passed anything that could remotely be called a “climate bill” since 2009; it has never passed anything with as many clean energy provisions as have been promised in the American Jobs Plan.

Take, for example, one of the plan’s hallmark policies: a clean electricity standard, a requirement for the country’s utilities to produce all of their power from carbon-free sources by 2035. (Picture the nation’s dying coal and natural gas plants replaced with solar panels, wind turbines, geothermal loops, and a new generation of nuclear plants.) According to modeling from the Environmental Defense Fund, that standard — combined with investments in the electrical grid and tax credits for building alternative sources of power — would get the U.S. more than halfway to its new emissions goal.

Then there is the $174 billion for jumpstarting the process of replacing America’s roughly 248 million gas-powered cars with electric ones. (Part of that money would go to tax credits, which can help Americans pay the higher up-front cost of owning an EV; another chunk would go toward building a gigantic network of charging stations where all those electric cars could plug in.) Not to mention the money the plan earmarked for research and development into clean energy, the climate corps jobs program, and on and on.

The problem for Biden is that Republicans in Congress don’t seem to want any of that. Their near-trillion dollar counteroffer is focused on “traditional” infrastructure, like roads, highways, and bridges. It gives almost no funding to clean energy, electric vehicles, or research and development. “The climate aspects of the Republican proposal are basically negligible compared to what needs to be done,” Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, a Democrat from Rhode Island, told me. “It’s an old-fashioned bridges and highways proposal with a little climate ‘purfling’ along the edges.” (Purfling, it turns out, refers to the decorative edge on a string instrument.)

Republicans’ unwillingness to get on board with the full American Jobs Plan isn’t a surprise; many Democrats have long assumed that, in order to pass climate policy, they would have to do it on their own, likely by making use of a Congressional loophole known as “budget reconciliation” in order to bypass the filibuster. (In the era of partisan gridlock, budget reconciliation — normally just a way to quickly adjust big budget bills — has increasingly been seen as a way to pass key policy.) But all the Democratic talk of (hypothetical) bipartisanship on infrastructure may be costing them valuable time to act on the (very real) threat of climate change.

“My experience has been that at the end of the day, Lucy tends to pull the football away from Charlie Brown,” Whitehouse said. Democrats, he pointed out, have only 18 months before next year’s midterm elections — when many Republicans think they will be able to retake the House. “As that time bleeds away, it becomes harder and harder to see how we get onto a safe climate pathway,” he said.

There is always the possibility that Democrats could work with Republicans on a watered-down infrastructure package, one built of mostly highways, bridges, and roads, and then follow up with a Democrats-only clean energy bill that goes through the tricky budget reconciliation process. Josh Freed, the director of climate and energy at the policy think tank Third Way, told me that he believes moderate Senate Democrats — like Joe Manchin of West Virginia, widely considered to be the crucial 50th vote on any Democrats-only legislation — will be motivated to pass any remaining clean energy components of the American Jobs Plan that way even if they don’t make it into the infrastructure package.

“I think that regardless of what happens with [infrastructure], there’s enough stuff that Manchin supports and wants to see passed because it’ll help West Virginia,” Freed said.

But, for climate activists who remember President Barack Obama’s failed efforts to pass climate legislation, any amount of waiting seems deeply dangerous. In 2009, Congress passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, an effort to pull the country out of the Great Recession, which included $90 billion for clean energy and was intended to be step one of slowing the pace of climate change. A bill enacting an economy-wide limit on carbon emissions was supposed to come later. But this second step got tied up in the Senate, and the Obama administration prioritized healthcare reform instead. Since then, average global temperature has increased by about 0.7 degrees Celsius — and the U.S. has still not passed a single piece of climate legislation.

Whitehouse said he has always expected Congress to pass both an infrastructure bill and a budget reconciliation bill — and in a perfect world, they would be planned simultaneously, so that the budget reconciliation bill, with all its clean energy provisions, doesn’t get held back by cross-party negotiations over infrastructure. “But,” he added, “I’m not sure it’s a perfect world.”