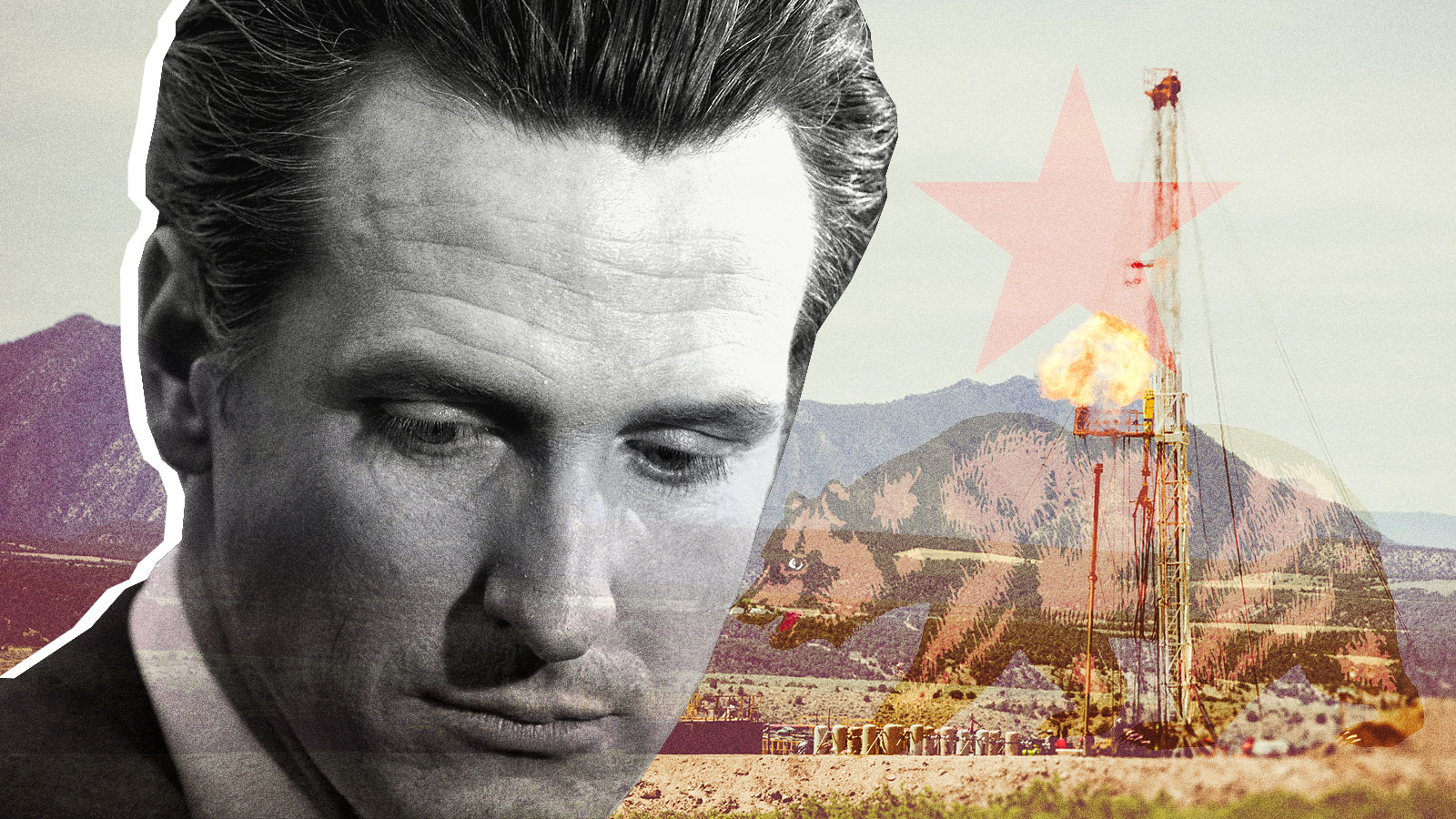

Alongside California Governor Gavin Newsom’s headline-making announcement last week that he would ban the sale of gas-powered cars by 2035, he also said he supported a ban on new fracking permits by 2024.

The announcement came in the middle of one of California’s most devastating fire seasons on record — thousands of blazes have consumed more than 3.6 million acres of land and claimed at least 26 lives. Earlier this month, Newsom declared them a “climate damn emergency,” pointing to the climate crisis’ tendency to make extreme events like wildfires more likely and more dangerous. In response, he has promised Californians his cabinet would “step up our game” and “fast track our efforts” on climate.

His executive order on gas-powered car sales was an attempt to make good on that promise, and it drew praise from environmental advocates. The fracking statement, however, prompted criticism. Many green groups said that 2024 is too late and that the governor should use his executive powers to implement the ban himself. Newsom claims not to have that power — on Wednesday, he instead urged lawmakers to consider banning fracking during their next legislative session, in 2021.

“He punted on fracking,” Colin O’Brien, a deputy managing attorney for the nonprofit Earthjustice, told Grist. O’Brien contrasted Newsom’s inaction with more aggressive measures that have been taken in other states. “The state of New York banned fracking by executive order five years ago, and to my knowledge there’s nothing unique about California law that would prevent [Newsom] from doing the same today.” In the past five years, Washington state and Maryland have also implemented fracking bans via legislation, and New York’s state legislature also codified its fracking ban into law earlier this year.

Activists said Newsom’s statement is a distraction from his track record on regulating the state’s oil and gas industry. When Newsom ran for office in 2018, he promised an aggressive environmental agenda, including opposition to fracking “and other unsafe oil operations.”

“I’ll fight efforts by the oil and gas industry to escape the reach of state and federal regulators,” he wrote in a December 2017 Medium post.

But in the first half of 2020, the Newsom administration issued 190 percent more oil and gas drilling permits than it had during the governor’s first six months in office. And from April to July of this year — as the COVID-19 pandemic was taking off — the state’s Geologic Energy Management Division (CalGEM) approved nearly 50 new permits for fracking projects.

Those permits started being issued immediately after the end of a nine-month moratorium on new fracking permits, which Newsom had implemented in July 2019 to allow time for the projects to be reviewed by a panel of independent scientists. Not all the permits have resulted in oil and gas exploration, and they expire after one year, but they have still raised concerns from environmental groups.

One of groups has called the spate of permit approvals illegal, citing insufficient environmental review and the serious threats that oil and gas exploration pose to California’s public health. On Monday, the Center for Biological Diversity’s Climate Law Institute threatened to sue the state unless the governor takes action to stop the permits. Alongside the danger of spills and explosions, the health hazards of fracking include air pollution from methane and ozone, water contamination from heavy metals, and the longer-term effects of climate change, with these impacts often hitting low-income and nonwhite communities the hardest.

“You can’t claim climate leadership while handing out permits to oil companies to drill and frack,” said Kassie Siegel, an attorney for the group, in a statement. According to one analysis, California is on pace to approve more than 3,100 new permits in 2020, a greater number than any year since 2015. A spokesperson for CalGEM told the L.A. Times that by issuing the permits, it is merely following the law, and that California standards for health and safety “exceed those of any other state in the country.”

Newsom has also drawn flak from environmental advocates for not using his executive powers to implement statewide guidelines for the use of “setbacks,” buffer zones that protect communities from nearby oil and gas wells. A state scientific panel recommended setback standards all the way back in 2015, and several other states have already implemented their own requirements.

“This is an immediate step he could take to provide relief to frontline community members,” said O’Brien. “California is really lagging behind.”

In response to criticism last week, Newsom defended his decision not to go further on a fracking ban. The 2024 phaseout deadline is a “bold and big step,” he told the Associated Press, adding that fracking in California only accounts for 2 percent of the state’s petroleum production. Although a ban would hold symbolic power, he said, “We simply don’t have that authority. That’s why we need the legislature to approve it.”

Sierra Club California Director Kathryn Phillips empathized with Newsom. Although his comments on fracking alone are insufficient, she told the Associated Press, “What he’s committed to is more than what any previous governor has committed to. This governor is now saying he’s going to work with the Legislature to get the power to ban fracking. That’s a good thing.”