Last fall, a company called Summit Carbon Solutions started holding meetings in towns around the Midwest. Its goal was to introduce residents to a 2,000-mile, $4.5 billion pipeline called the Midwest Carbon Express, which would carry carbon dioxide from ethanol refineries in Iowa to North Dakota, where the gas would be injected underground rather than released into the atmosphere. Ultimately, Summit hoped landowners would sign contracts called “voluntary easements,” allowing the company to bury its pipeline on their property.

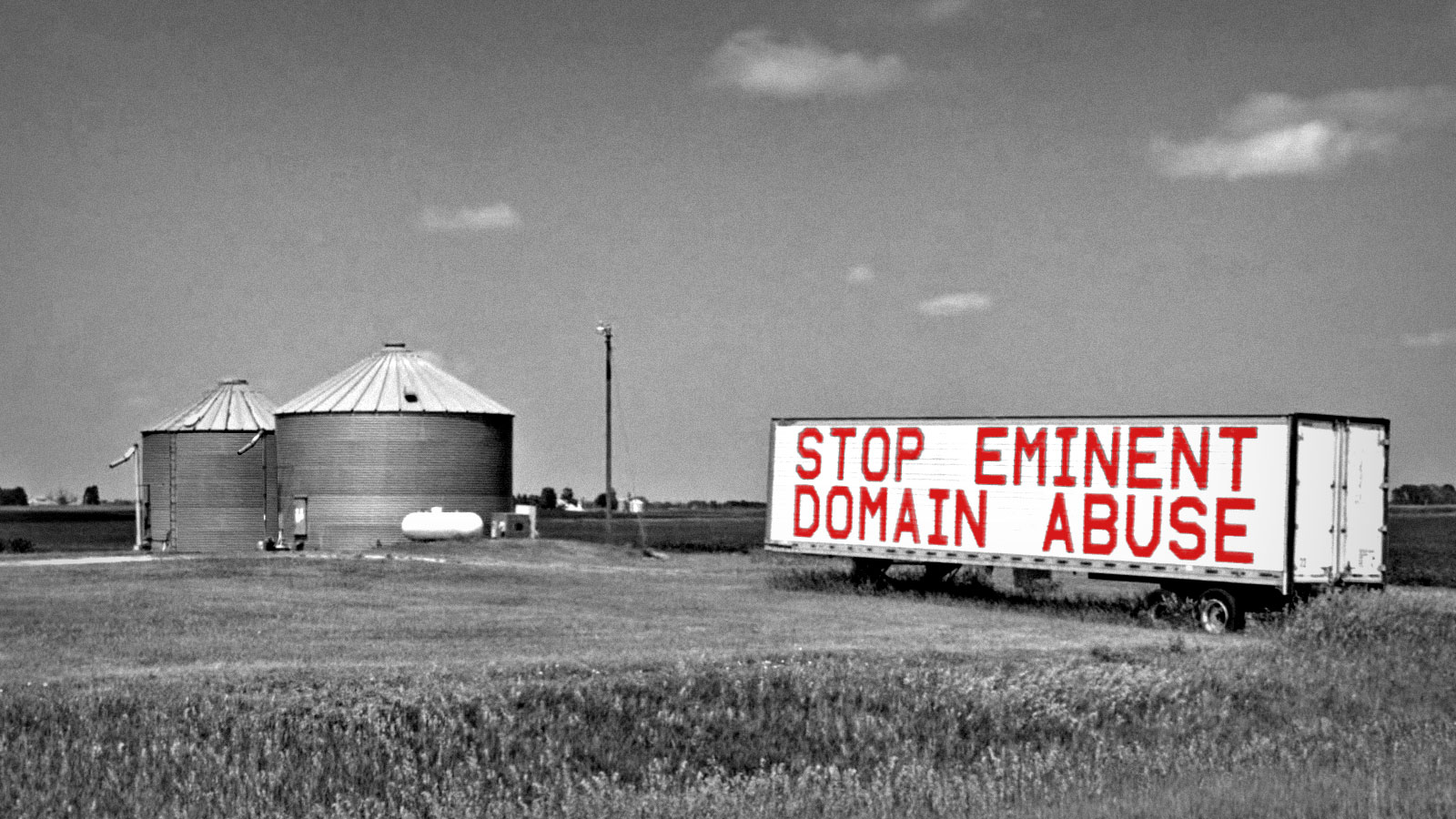

While hundreds signed up immediately, others were more cautious, hoping for more information or a better price. Now, those holdouts are facing another prospect: the use of eminent domain, the legal tool that allows the seizure of private land for public good. It’s a tactic that’s long been tapped for other pipeline projects in the Midwest, and Summit has filed preliminary permits that could allow the company to request permission to use eminent domain in the future.

That doesn’t sit well with many landowners along the pipeline’s route. In town hall meetings and public hearings over the past few months, a growing number of people have come out against the proposal and potential legal tactic, complicating Summit’s plans to build the largest carbon dioxide pipeline network in the country.

Opposition to the project – and other recently proposed carbon pipelines – is nothing new. Residents and activists have raised concerns about safety hazards, a sentiment echoed in May by the Biden administration. Environmental groups, meanwhile, have pointed out the dubious climate benefits of carbon pipelines and resulting carbon capture and storage, or CCS, saying it will lock in additional fossil fuel use and divert resources from the transition to renewable energy.

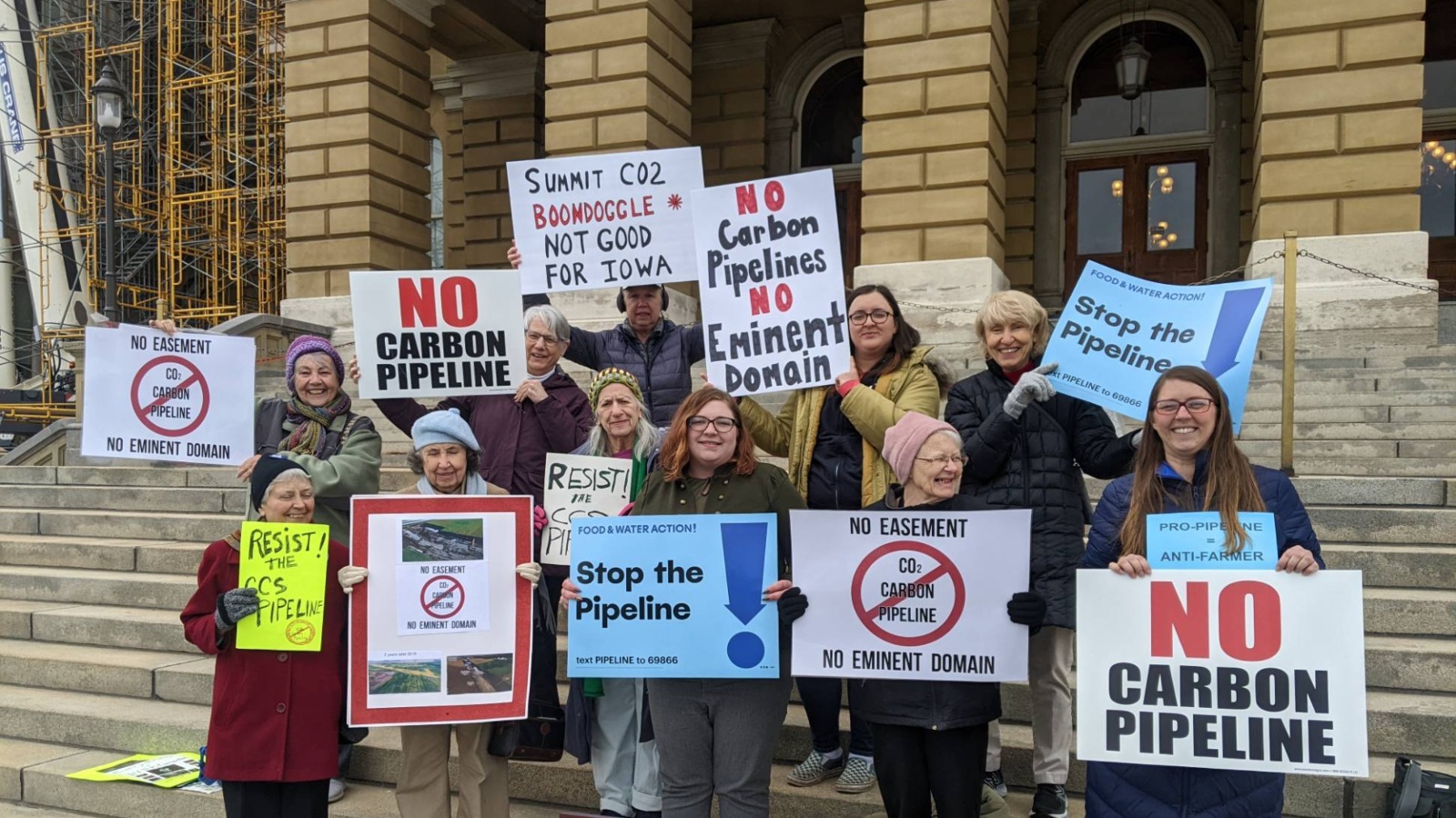

But eminent domain has become an issue around which an “unlikely alliance” of farmers, ranchers, Indigenous tribes, scientists, and environmentalists have rallied, said Mahmud Fitil, an organizer with the Great Plains Action Society, an Indigenous activist network. The legal tactic was used to complete previous oil pipeline projects like the Dakota Access Pipeline, which “left a bad taste in a lot of people’s mouths,” Fitil said. Now, rural conservatives and environmental groups are fighting the same battle against carbon pipelines.

“You would never find these groups of people gathering together for any reason,” Fitil told Grist. “And they’re coming together in opposition to this carbon pipeline.”

Eminent domain is enshrined in the U.S. Constitution, allowing governments to seize private property as long as they compensate the owners. In states like Iowa, this right extends to private companies, too. Although it’s historically been used to construct infrastructure like highways and natural gas lines, some environmental advocates believe eminent domain could be an important tool in the renewable energy transition, allowing electric transmission lines to be built quickly to transport solar, wind, and hydropower energy across the country.

Using it, though, requires utilities and private companies to prove that a project is in the “public interest” — and many people in the Midwest don’t feel that carbon pipelines fit that description, said Don Kass, a farmer and chairman of the Plymouth County Board of Supervisors in northwest Iowa.

“I do not consider this to be a public utility … [just] because somebody’s making money on it, and people see that there’s some advantage,” Kass said. He’s not against pipelines in general, but believes it should be up to each individual landowner to decide whether to sell their land or not for the price that they’re being offered.

Although carbon pipelines would cross multiple states, the greatest concerns about eminent domain have so far come from Iowa, where three pipeline companies announced projects last year that would collect carbon dioxide from ethanol plants around the state. But strong relationships between politicians, lobbyists, and pipeline companies have made fighting the projects an uphill battle, organizers say. A bill that would have prevented the state from granting eminent domain rights to private projects like carbon pipelines stalled in the Iowa legislature earlier this year, despite bipartisan support.

In response to these legislative setbacks, organizers have taken a more grassroots approach. According to Food and Water Watch, a national nonprofit that’s organizing against the carbon pipelines, 32 out of 52 counties that would be impacted by the proposed pipeline projects have filed objections with the Iowa Utilities Board. The board will ultimately decide whether to grant Summit and the other companies, Navigator Ventures and Wolf Carbon Solutions, a permit to use eminent domain. (So far, only Summit has applied for a permit with the board, and none have officially requested to use eminent domain).

The groups rallying behind their opposition to eminent domain all have different reasonings, said Emma Schmit, a senior organizer for the Iowa chapter of Food & Water Watch. Some worry about the pipelines’ impact on climate change and the environment as well as potential safety hazards, and think fighting eminent domain will prevent the projects from being built. Rural conservatives, meanwhile, believe in the right to protect their private property. “They don’t want to be seeing these private corporations, Wall Street-backed industry, taking our land for their own use,” Schmit said.

Landowners in Iowa also remember their previous experiences with the Dakota Access Pipeline. The project was completed in 2017 despite pushback from farmers, who worried about the impact its construction would have on agriculture. Their concerns were validated earlier this year: A study from Iowa State University found that crews building the pipeline compacted the soil so much that crop yields along its route dropped by as much as 25 percent.

“During our first meeting on this issue, we made a point to say that we’re all affected by this, we all have different reasons for caring about this issue,” Schmit said. “But no matter what your view on this is, we can all agree that it’s bad, and we have to stop it. And we can only stop it when we come together.”

This diversity of viewpoints can sometimes cause friction. The property rights argument can be “controversial,” Fitil said, “particularly amongst Indigenous people, given that all the land is stolen in this nation from the rightful owners, the Indigenous folks that made this land home long before European contact.” But organizers nevertheless felt it was important to have a unified strategy, and have managed to convince some Indigenous leaders to join in their opposition. Schmit said the failure to bring landowners, tribes, and environmentalists together was one of the reasons they lost the fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Proponents of the CO2 pipelines have made the case that the projects will support Iowa’s powerful ethanol industry, which buys 57 percent of the state’s corn and produces 27 percent of the country’s ethanol. Companies also have a financial incentive to sequester carbon thanks to federal tax credits like 45Q — which Mother Jones estimated would earn Summit $7.2 billion over 12 years — and state programs like California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard, which allows ethanol plants and carbon pipeline companies to sell the carbon they’re saving as credits to polluters. The federal government has also supported carbon capture as a way to reduce carbon emissions, while Congress established a low-interest loan program for CO2 pipelines last year.

Summit told Grist its priority is getting landowners to sign voluntary easements, rather than using eminent domain. About 30 percent of landowners along the proposed Midwest Carbon Express route have already made deals with the company.

“Opposition groups continue to raise this topic in order to distract from the fact that they want to eliminate the ethanol industry and undermine production agriculture,” Summit said in a statement through a spokesperson. “Fundamentally, the Summit Carbon Solutions project comes down to the future of these two industries, which are both so critical to our economy.” The other two pipeline companies with proposed projects in Iowa, Navigator Ventures and Wolf Carbon Solutions, did not respond to requests for comment from Grist.

Schmit said this early in the process, activists are still “throwing everything possible at the wall” and seeing what sticks. Organizers have hung banners off of freeway overpasses, rallied in front of the Iowa State Capitol, set up billboards in rural areas, and held meetings in communities where pipelines are expected to cross. Reaching residents along the pipeline’s proposed route has been difficult, though, because Summit has sued to stop the Iowa Utilities Board from releasing the full list of landowners that will be potentially impacted by the project, said Wally Taylor, an attorney for the Sierra Club in Iowa.

Taylor emphasized that even if eminent domain is granted, landowners can still band together at the county level and demand concessions from the company, including greater compensation — which might ultimately discourage the pipelines from being built. After the Iowa Utilities Board granted a permit allowing the Dakota Access Pipeline to use eminent domain, he said, many people gave up and granted voluntary easements. Activists said they have learned from that mistake.

“They said, ‘Well, there’s nothing we could do, we’ll just go ahead and take our money,’” Taylor said. “But we’re really trying to convince the landowners that if they hold out, they can stop this.”

*Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the number of companies that have applied for eminent domain permits.