A bill that could stifle environmental protests has emerged in an unlikely place: the Democrat-controlled Oregon state legislature. Lawmakers in the Beaver State are considering a bill that could make “disruption of services” provided by so-called critical infrastructure, which includes roads, pipelines, electrical substations, and some oil and gas infrastructure, a felony punishable by up to 10 years in prison and $250,000 in fines. The bill labels such activity “domestic terrorism.”

The bill’s sponsor, Democratic state Representative Paul Evans, and other proponents argue that the legislation is necessary to adequately punish extremists who may seek to damage facilities that provide essential public services. The bill appears to be a direct response to the 2020 racial justice protests that turned violent in Portland and the breach of the state capitol in Salem by far-right protesters the same year. A recent report by the Oregon Secretary of State claims that the state has experienced one of the highest rates of domestic violent extremism in the country and that critical infrastructure “continues to be a high-risk target.”

“What happens when someone decides that for a fun evening they’re going to go out and destroy an electrical substation that cripples a community for a day, a week?” Evans said during a committee hearing. “The fact is we have some gaps in the way in which we approach those sorts of crimes.”

But existing state laws already make trespassing and property damage criminal offenses, and environmental and civil liberties advocates are concerned that decreeing “disruption of services” to be domestic terrorism could result in charges for nonviolent protesters who may block a road, bridge, or oil and gas site during a protest.

“That’s stuff that could happen at ordinary protests,” said Nick Caleb, an attorney with the environmental nonprofit Breach Collective. Caleb said that this bill may not have received much traction prior to 2020, but that the violent events of that year changed the calculus for many lawmakers. “Suddenly there’s enough Democrats that also think labeling things as terrorism will have an effect on stopping that type of disruptive activity,” he said.

The bill is still in the early stages of consideration. It successfully passed out of a state House committee and has received a hearing, but it has several more hurdles to clear in both chambers before it can become law.

As state legislatures kick into high gear this year, many other states are proposing and passing similar legislation. In the last few months, state legislatures in Georgia, Tennessee, and Utah have all passed bills that increase penalties for interfering with or damaging critical infrastructure. A number of other states — including Minnesota, Illinois, North Carolina, and Oklahoma — have similar legislation pending.

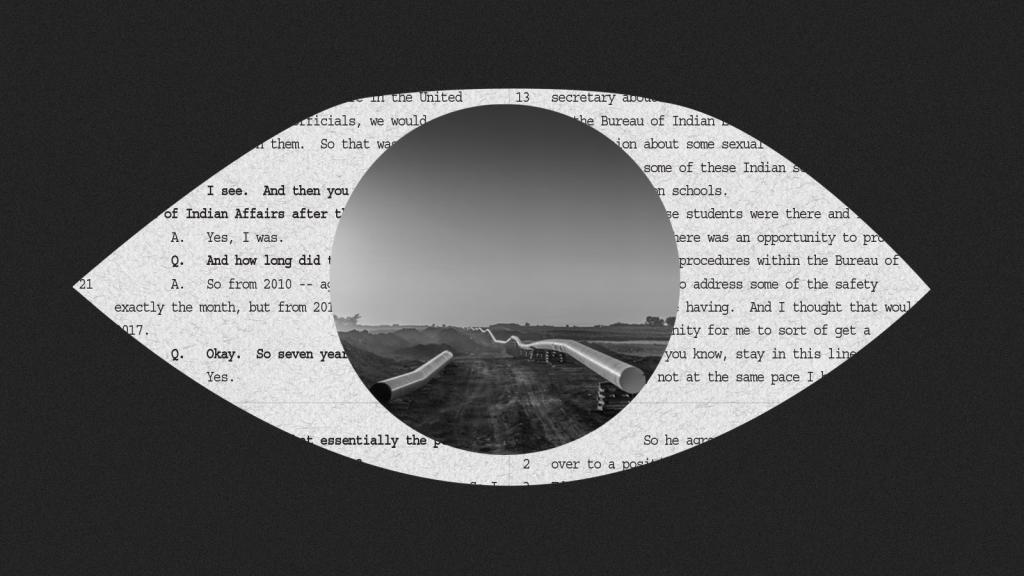

Over the last six years, at least 19 states have passed this kind of critical infrastructure law. The bills were first proposed after the 2017 Standing Rock protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline received national attention. In response, primarily Republican lawmakers explicitly cited the Standing Rock protests as the impetus for the legislation. But this year, lawmakers have mostly pointed to a more recent spate of attacks on electrical substations in North Carolina, Washington, and Oregon as the reason such critical infrastructure bills are needed.

Advocates in Oregon have pointed to other events in Georgia as an example of the ways in which a domestic terrorism bill could be used to target protesters. Georgia lawmakers first expanded the state’s definition of domestic terrorism in 2017 to include crimes committed with the intent to “alter, change, or coerce the policy of the government.” Since then the law has been used to target environmental activists protesting the construction of a police training center colloquially referred to as “Cop City.” Of the roughly two dozen protesters arrested under the law, arrest warrants showed that several were being charged with domestic terrorism even though they weren’t alleged to have engaged in any specific illegal activity other than trespassing.

“There was a stated reason for why the [Georgia] law was passed — to target mass shootings,” said Sarah Alvarez, a staff attorney with the Civil Liberties Defense Center. “Now it’s being twisted to apply to environmental protesters who haven’t harmed anyone. That is the concern that I have when I look at the Oregon bill.”