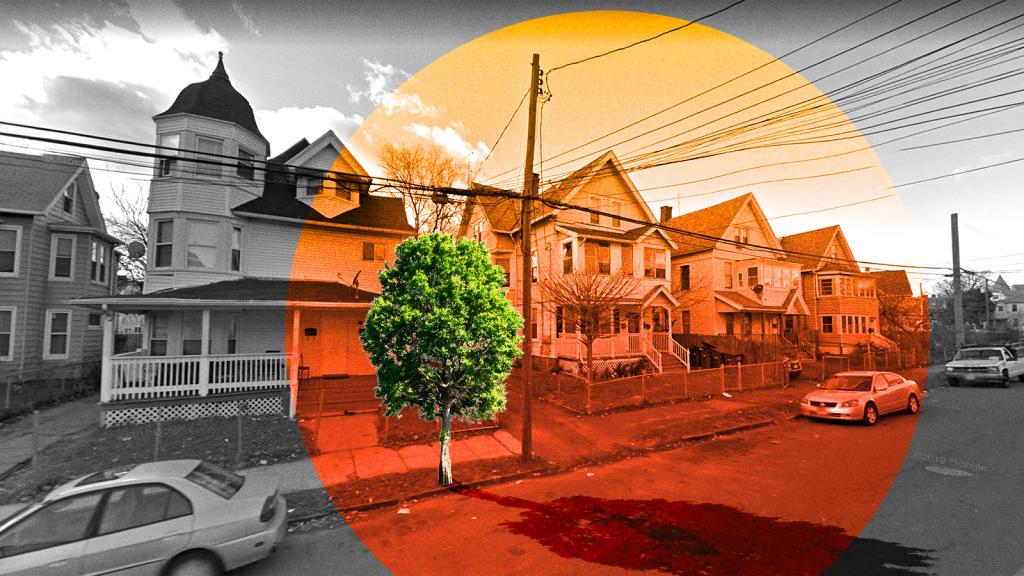

Picture this: two babies born on the same day, maybe even within the same hour, at the Harlem Hospital Center in New York City. One baby, born to a Black mother, goes home to her family down the street in East Harlem. The second is taken home just a few blocks south to the Upper East Side by her white mother.

Fast forward to these babies’ adulthoods, and they’ve stayed close to the people and places they’ve grown to love — but their ability to access things like fresh food, quality pharmacies, well-resourced schools, clean water, and even something as simple as the trees that shade their blocks are drastically different. The way their communities are policed and incarcerated is substantially different, too. As a result, the two people are expected to die roughly 19 years apart, despite living just a few blocks from one another.

A new study and interactive map from researchers at the University of California Berkeley’s Othering & Belonging Institute, or OBI, demonstrate a comprehensive attempt to better understand residential racial segregation, the common phenomenon at root of these disparate inequalities, across the U.S. The study finds that, while residential segregation declined modestly from 1970 to 1990, it began increasing in 1990 and has been getting starker ever since. As a result, more than 150 large metropolitan regions in the U.S. — a whopping 81 percent of the total — are more segregated now than they were 30 years ago, according to the study.

“Segregation is the invisible undercarriage of every expression of systemic racism in this country,” Stephen Menendian, lead author and Director of Research at OBI, told Grist. “While segregation might not explain everything with inequality, it’s the sine qua non of racial inequality, which has a role in all injustices.”

The study’s sobering results are partially the result of careful methodological choices. Rather than relying on traditional measures of segregation like the so-called Dissimilarity Index, which measures how much movement it would take for two racial groups to become evenly distributed in a given locality, the researchers opt instead to use the Divergence Index, which measures the extent to which the demographics of a given geographic unit diverge from the broader whole of which it is a part: how the demographics of a census tract differ from those of its city, or how those of a city differ from those of a broader metropolitan area. The authors say that this better allows the study to account for America’s increasing diversity (which could lower dissimilarity scores even as segregation itself persists) as well as the increasingly regional nature of segregation.

This methodology finds that the one-time manufacturing hubs of the mid-Atlantic and Midwest’s “Rust Belt” disproportionately account for the country’s top 10 most segregated cities, with Detroit — the Blackest city in America — topping the list. Chicago, Cleveland, Milwaukee, and Philadelphia are not far behind. When metropolitan areas, which include cities and their connecting suburbs, are considered as a whole, New York City reigns supreme. While segregation is worst in these places, it has increased all across the country. Since 1990, the metropolitan area of Fayetteville, Arkansas, has seen the greatest increase in segregation, while cities in the West, such as Salt Lake City, Utah, and Santa Cruz, California, have also become significantly more segregated.

Segregation may have picked back up in recent decades, but its roots stretch back much further.

“The real driving force behind segregation in the North and West,” Menendian explained, “was the real estate industry.” Real estate companies have historically propagated racist beliefs that Black residents negatively impacted property values, were undesirable neighbors, and posed existential risks to communities and neighborhoods. As the government got more involved in regulating housing in the early 20th century, these ideas made their way into official policy. With that came exclusionary single-family zoning policies in places like Berkeley, California; racially restrictive zoning ordinances in cities like Baltimore, Maryland; and the nationwide practice of redlining, which denied investment to communities of color from Chicago to Miami and everywhere in between.

Segregation’s hold on the country has led to Black and Latino communities’ disproportionate exposure to environmental pollutants, which when coupled with poor health care options, unhealthy food options, as well as less access to green space and even safe jobs, culminates in a predisposition to premature death: Today Black Americans are expected to live six fewer years than white Americans.

Another new study by the conservation nonprofit American Forests found that segregation can even account for something as mundane as why affluent U.S. communities have 65 percent more trees than their poor counterparts. Closing that tree cover gap would support 4 million jobs, mitigate 57,000 tons of air pollution, and remove the equivalent amount of carbon from the atmosphere as taking 92 million cars off the road, according to the group. It would also improve health and safety outcomes in poor communities. (Tree cover has been shown to help lower blood pressure, reduce stress, and increase energy levels.)

However, Medendian and his co-authors Arthur Gailes and Samir Gambhir believe that fixes that focus on the symptoms of segregation, such as tree cover inequality, without addressing the deepening segregation itself won’t make any substantial differences in disparate life outcomes.

“In this particular moment of greater awareness of the extent and reality of systemic racism in the country, it’s important that we draw attention to what undergirds injustice,” Menendian said. “Segregation causes the inequalities that lead to police patrolling certain neighborhoods more aggressively, why life expectancies are lower in some neighborhoods than others, why frontline workers are disproportionately residing in certain neighborhoods, and why some people don’t have access to clean air or water.”

“If we’re going to actually make progress on these inequalities we need not continue focusing on the symptoms, but the causes,” he added.