This is Season 3 Episode 1 of Grist’s Temperature Check podcast, featuring first person stories of crucial pivot points on the path to climate action. Listen to the full series: Apple Podcasts | Stitcher | Spotify

“I would like to see the Mississippi River clean and not full of chemicals, because the industries, they dump benzene in the river, in our drinking water. They dump formaldehyde in our drinking water, and other chemicals. But my dream is to see St. James the way it was when I was a little girl. That’s what I would love.”

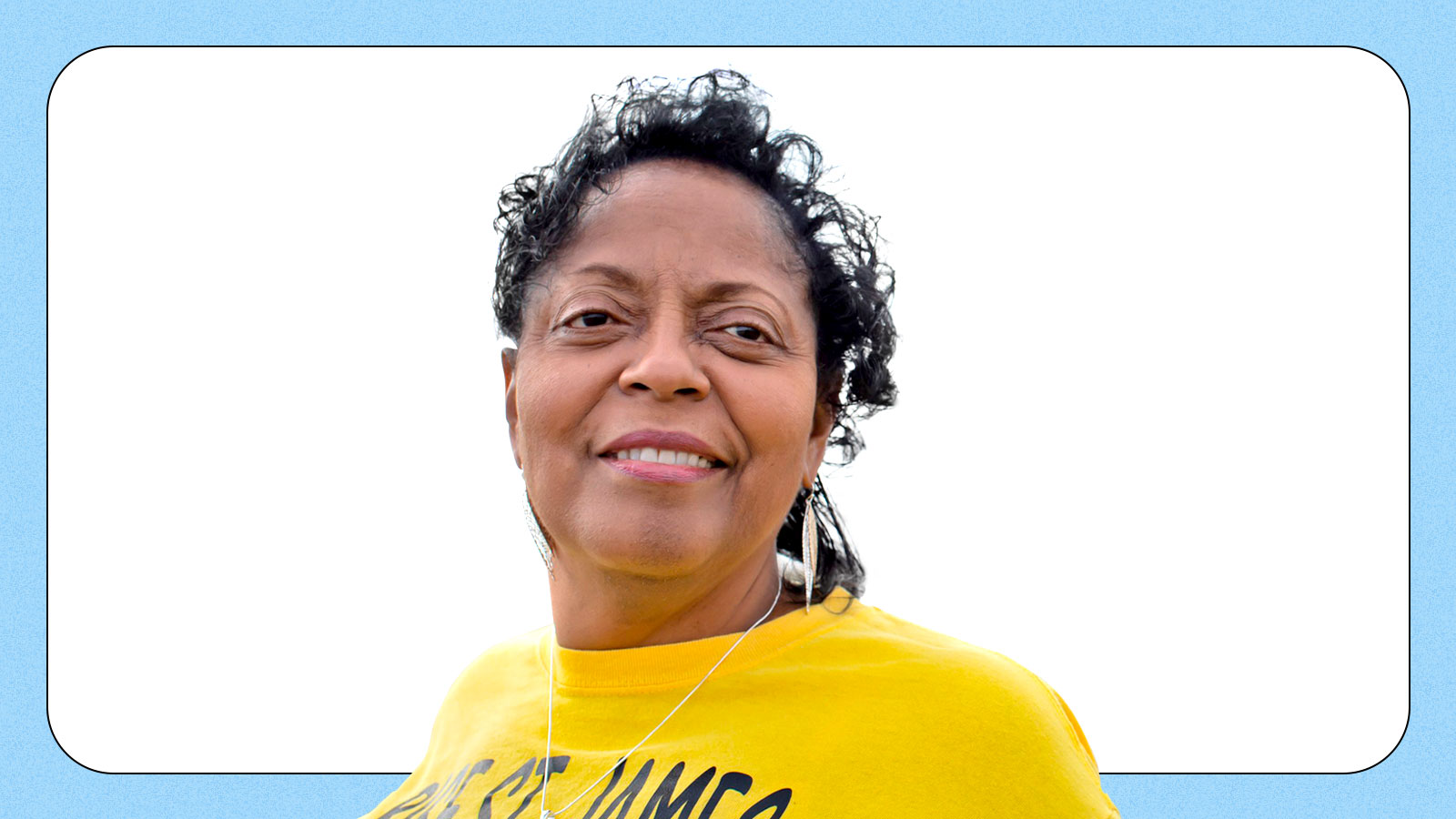

– Sharon Lavigne

Episode transcript

Sharon Lavigne lives in St. James Parish, Louisiana, in an area known as “Cancer Alley.” If you haven’t heard of it, Cancer Alley is an 85-mile stretch of petrochemical plants, oil refineries, and other industrial operations that runs from New Orleans to Baton Rouge along the Mississippi River. Air pollution in the area means that residents face a lifetime cancer risk estimated to be up to 47 times higher than what the EPA deems acceptable. And Black communities are hit the hardest.

Sharon spent most of her life as a special education teacher. But as the years went by, the air quality in St. James Parish got worse and worse. Eventually, Sharon learned the connection between the plants, the air and the terrifying rates of sickness and death in her community, and she decided to do something about it. This is her story.

My name is Sharon Lavigne, and I’m 70 years old, and I am an environmentalist and the director and founder of RISE St. James.

I grew up in St. James Parish in a little area called Chatman Town, and we had gardens of vegetables. My daddy raised cattle. We ate off the land. We grew everything … just about everything. In the wintertime we would have figs. My momma would cook the figs in the summer and preserve the figs. And that would be for our meals in the winter. And by then we would have the fresh cow milk. You’d milk the cow and the next day, we would have this fresh cow milk, because we put it in the refrigerator and it’d be nice and cold and taste good. We didn’t have to buy eggs or milk or anything like that. We got it off the farm. And my daddy raised the hogs, we ate pork. And to me, it was a dream come true.

The air was clean. I could breathe the air when I walked out of the door. And we weren’t sick. We didn’t have any type of illnesses or anything. We didn’t have any sinus problems, I can tell you that much. We didn’t have sinus – I didn’t even know what sinus was. I didn’t even have headaches. I didn’t have anything wrong at the time.

When the first plant came, my daddy was in politics and he was an environmentalist or leader, whatever you want to call him. And I could hear him telling my momma, “Ooh we got a plant coming to St. James and blah, blah, blah,” all excited. And we all started to smell things, but we didn’t let it worry us, because we really didn’t know what it was anyway. We just smell something.

Plants line the Mississippi River in the area known as “Cancer Alley.” (Giles Clark/Getty Images)

You better not take a deep breath today. You will get a breath full of chemicals going down your throat. And you see, within a ten mile radius we have 12 industries, and that’s all you see. At night it looks like it’s lit up like Christmas time it’s so many lights out there. And flares. Sometimes flares late at night, sometimes early in the morning, and sometimes during the daytime. I’m so tired of driving down Highway 18 and get a smell of these chemicals. Ammonia, different smells, and sometimes it smells like a rotten egg. A smell that goes down to your throat. And sometimes my throat burns.

I have a friend right now with liver cancer and it’s spreading. We have another friend that used to cut the grass in the graveyard. He is down with cancer right now. He can’t work anymore. I have two brothers with cancer. One had the prostate taken out. And they both worked at plants. My brother’s wife, the one that had the prostate cancer, his wife died with cancer in the breast, and she worked at industry. That was a friend of mine, we were the same age. Sometimes I don’t like to talk about it. It hurts. And I feel like .. I feel like we are next. I just feel like that.

I’m going to a funeral Saturday. I have a funeral tomorrow of a friend. I imagine myself laying in that casket. I really do. Especially friends that I know that died because of industry. We just buried one of my friends. He was working at a plant, and his wife says she know the plant caused him to get sick after 40 years. And she say – she hugged me so tight and she told me that she think it came from there. That’s what I think so too. Other people say, “Oh, no, it wasn’t because of that, it was stress.” I say it might have been stress because of that. So I have people are trying to dispute it. If we only had the proof, if we only had a toxicology lab that we can take samples and have people working in there and really let the world know what they’re doing to us. I know it’s industry. It wasn’t industry before. People were stressed. They wasn’t dying because they was stressed. You pray and you get over the stress. But you can’t get over those chemicals in your body.

I started teaching back in the ‘80s and I didn’t pay attention to the industry. All I know I’d pass in front of them, but I used to smell things. I said, “What that smell is?” and just go on about my business. And I thought everywhere was smelling, I didn’t know it was just St. James. I know that sounds crazy for me to say something like that, but I thought the world was smelling, not knowing that we have industry here and it could be the reason why I’m smelling this. I never once thought that when I first started teaching.

I was a special education teacher and I taught regular ed for one year. My first year I worked for Assumption Parish. I taught the severe profile. They were really special ed. And then – I stayed out a year, then I started back in St. James Parish. My daddy told a school board member that his daughter paid tax in St. James and she wanted to get a job in St. James. They created me a job, and they asked me what school I wanted to be at, and I told them “the high school.” So I was at the high school. When I went to the high school I was teaching English, science, social studies, and math. It wasn’t to the severe profile children. It was children – they were regular ed but they might have been weak in one subject. They might have was weak in English or reading or math. And so those are the ones that I taught that was called “slow learners.” And then I left from there and they asked me if I wanted to work with the severe profile. I said, “I don’t care.” When I retired, I was teaching the severe profile.

I was a teacher that showed compassion. I was a teacher that really cared, and I wanted the students to learn. And when they didn’t come to school, I called the house to find out why they didn’t come. One lady said, “You the only person that does that.” You gotta care about your job, care about the children, not just doing it for a paycheck. Trust me, the children know if you care. And don’t talk down to them. If you talk down to the students then they’re not going to want to listen at you teaching them. So you try to build them up. Like if your child in the classroom and he made a D on his test, and his friend made a B, they might make fun of the one that made the D. And I would tell him something nice to make him feel well, you know, you made a mistake this time, but it wasn’t that big of a mistake. Next time, you’re going to do better.

I really enjoyed the students. And for Christmas, I’d like to give them a little Christmas party or something. And I used to bake a cake and bring it to my classroom, give it to my students. And sometimes I’ll give them a hug. They were nice. They were nice students. And I loved them all. I really did.

It was years ago when I started noticing the smell. But as the years went on, the smell got worse. It started off a little bit and it got more and more and more. I noticed the last few years of teaching school that the students had so many doctor appointments. And I also noticed the increase in students in special ed, especially with asthma and different illnesses. And I thought maybe it was too many. I thought maybe you should have a decrease in students diagnosed as special ed. But it was an increase. I didn’t know what was going on with them. I didn’t think, you know, to even ask at that time.

In the year 2015, I noticed funerals. A lot of funerals. And I kept wondering, why all these funerals? And a few times we had a funeral twice a week. And once or twice we had funerals three times a week between Ascension Parish, St. James Parish, and St. John the Baptist Parish. Sometimes I’d call people over there, they going to a funeral. Call people in St. John sometimes they have a funeral on the same time with us. And it brought attention to me. Why so many funerals? Why are people dying? What’s going on? I didn’t know what was going on. The funerals didn’t stop.

I had a friend named Robert Arceneaux. He lived two houses down from me and he would go in the Mississippi River and fish. And I said, “Robert, the water is polluted.” And Robert said, “Well Sharon, you just have to cut the belly of the fish out.” It was just like jelly. I said, “Robert, I’m afraid to eat that.” He thought I was playing. I said, “No, you can cut the belly out all you want. I’m not eating that fish, Robert” And Robert say he was gonna eat it. And then he ate it. And then Robert passed away with throat cancer. That was my friend. He passed away. Yes, it was scary. I thought the world was coming to an end.

In 2015, I went to a meeting. Never been to a meeting in the public – never had a reason to go to a meeting. So I went to this meeting and they asked me if I wanted to join HELP. And I asked them what was HELP. They told me it was Humanitarian Enterprise of Loving People. And I said, “Okay.” So I joined. I I just didn’t want to sit at the house when I retired, because I was getting close to retirement. And then I said I might as well join this organization and see what’s going on in the community, and I might figure out what I want to do. I said, I might want to help the senior citizens. I might want to do something. I might want to drive people to the doctor that don’t have cars.

So when I joined HELP, they had so many stories about the plants and the industry, the refineries and all that in St. James. I didn’t know we had all of these things in St. James. I didn’t know we had that many. And so I learned, and I learned that it was Cancer Alley. I started learning about it and reading about it and hearing about it, reading the newspaper and stuff. And the more I read, the more I was disgusted. One day we rode down Highway 18 within a ten mile radius and we counted 12 industries. And that blew my mind away. It just blew me away. Twelve? We breathing this stuff? Twelve? Oh my God. When I realized that this was called Cancer Alley, I felt like we didn’t have long to live. I felt like it was a death sentence to us. I really felt like that.

In 2016, I went to the doctor for my bloodwork – my annual checkup – and the doctor said, “What’s wrong with your liver?” I thought she was joking. You know, she’s a nice lady – I thought she was joking with me. I said, “My liver?” I said, “My liver is fine.” She said, “No, these numbers are not right, Sharon.” I said, “Not right?” I said, “What’s wrong?” And she said, “I’m going to send you to a gastrologist.” That’s when the gastrologist diagnosed me with autoimmune hepatitis. He gave me some medication to take. And then he told me I have to take that for the rest of my life. One article said it came from industrial pollutants. And I said, “That’s my answer.” These plants are killing us. That’s why I’m sick.”

In 2018, a company called Formosa Plastics announced plans to build a $9.4 billion petrochemical complex in St. James Parish. The plant would be two miles from Sharon’s home.

I asked HELP if they would do something. Can we stop it? And they said no, because the governor approved it. And they said no, because the parish council is going to approve it. And they said, “No, when the governor approves it Sharon it’s a done deal.” And that angered me. And I said, “Well, the governor don’t live here. He lives in another area and he’s not going to be polluted. It’s going to be us.” It’s like they’re making us a sacrifice for them to make the profit to run the state.

We would have the meetings – the HELP association meetings – once a month. And we would go home, me and Geraldine and Beverly – and we would talk in the meeting about why we don’t do something, and they would say this and that – so we’d get in the car and we would argue in the car angry. We don’t know why they don’t want to stop this. This plant should be closed. This plant shouldn’t do this. The plant is polluting us. We’ll be arguing, you know, amongst each other in frustration. Geraldine said, “Lavigne, you need to start another organization.” I said, “Not me. I don’t know anything about starting an organization.” She said, “Well, Lavigne, somebody’s got to do something.” I said, “Well, Geraldine, you could start one and I’ll come to your house.” And she kept telling me that. She didn’t just say it one time. And Beverly said it a couple of times, and we would talk about it. Oh, we was so angry and upset.

So I would go home at night from that meeting. I would take my bath, get ready for bed, and lay in the bed and talk to God. But God didn’t answer me. I guess I didn’t wait for an answer. I just told him what was going on. I told him the problems and I told him people are already dying and I just spilled my guts out to God. Then I’d fall asleep. But I didn’t wait for an answer.

Then, I think it was a Sunday afternoon. I watched the cardinals – the red cardinals. It was so pretty. Going from one tree to the next. And I said, “Just look at that. It’s so beautiful.” And we say the red cardinals means change. So I said, a change is going to come. I wonder what the change is going to be. I thought maybe the plants would go away or shut down or something. That’s what I thought. I used to read my Bible – sit on the front porch, read my Bible. People pass and wave. People in St. James are very friendly. They’ll wave at you.

So I sat on my porch that Sunday and watched the red cardinals. Then I was talking to God like I’m talking to you. And I said, “Dear Lord, do you want me to sell my …” I had already been talking to him, but I remember these words, and I said, “Dear Lord, do you want me to sell my home?” And I did my arm out like that toward the house. And I said, “A home that you gave me.” And I wasn’t waiting for an answer. But that time I didn’t run to the next question. I just waited a second or two. And he answered me. I could have jumped out the chair. But it startled me, and his voice was mostly in the right ear, like he was sitting on my right side.

Then I said, “Dear Lord, do you want me to sell the land, the land that you gave me?” And I said, “My grandparents’ land.” And he said, “No.” Again. And lord, when he said no again I didn’t know what to do. And he was still on that right side, right next to me. And then I said what did he want me to do? And he said, “FIght.” Fight? “I don’t know how to fight,” I said. I didn’t know how to fight. And the birds kept going back and forth. And then I started crying. The tears just flooded my face.

After that, days later, I told some of the people as a member of the HELP association that we’re going to start our own organization. Geraldine was so happy. Beverly was so happy. And I said, “We gonna have a meeting. It’s gonna be at my house.”

It was almost ten people there. And so we had it at my house, and Shamell took the notes. Shamell is my oldest daughter. Everybody was talking and expressing their concerns. Lynn Nicholas was there. My brother Milton was there. And Geraldine, and Beverly. And then I sat in the chair in front and I asked them, “What do you all want to do? How are we going to fight this?” Not knowing anything about this and everything just came from the top of my head. And we started writing down what we wanted to do, and we’re gonna have another meeting and all that good stuff.

So I went to a meeting at Southern University law school. They invited me to come. I went – about four of us went. And that night Shamell and I spoke to the people to tell them what’s going on in St. James. They didn’t know. I thought they knew. I thought everybody knew what was going on in St. James. I didn’t know the people didn’t know. The attorneys, counselors, NAACP, these people were there and listening to us. So the next day, I went back to the meeting, and then me and two other ladies stood up in front of people with a poster to show them different things that’s going on in St. James with the industries. And the people gave me their cards. They came up to me and wanted to talk to me. I didn’t know what I was doing. All I knew was they’re listening to us. And that’s where I knew it was going in the fast lane. It just like God was in charge, and just like God is the pilot in the jet plane and we are the passengers. And God is going fast. It’s going real fast. It’s going so fast until I look – I didn’t know what I was doing, but God was doing it and everything was being done right.

Back in 2018, on November the third, that was our first march. And that’s when we first speaking as a RISE member. We had the bull’s horn and I spoke on the bull’s horn. That was the first time I ever spoke in public. And then I said, “Formosa, this is the stop. You will not be built here.” And I mean it. They will not be built here. And then we marched in May of 2019. That’s how fast things were moving. We marched for five days from St. John the Baptist Parish to Baton Rouge, where the capital is.

But in September of 2019, Wanhua, a chemical plant from China – they were trying to be built on the east bank of St. James Parish, and they pulled out for some reason with the land, and also because we made noise. We went to the parish council meeting, we had marches, wrote letters, and they pulled out. That was our first victory. And our theme song is Victory is Mine.

I was surprised about that victory, because we had just started. And it came to an end so fast, because the newspapers said RISE St. James and other organizations were fighting against it, so they had community opposition, so that helped them to get out of here. And then the next one was South Louisiana Methanol. That was in September 2022. But the focus was mostly on Formosa, because Formosa would be two miles from my home.

We did videos against Formosa. We called out the H.R. person that’s working with Formosa. And we talked about the people that’s over LDEQ – Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality. We wrote them letters, went to the office to do an action. They wouldn’t even come out the office. And we protested against the governor. He still won’t stop Formosa. We did a billboard and signs saying “St. James is our home. No Formosa.” “Formosa you are not welcome here.” We went to the parish council meeting, asked them not to vote for Formosa. They totally ignored us and they voted for Formosa. Our own parish council members. And we voted them in. They are supposed to protect us, not protect industry. To listen to these council people vote for Formosa … it was heartbreaking. It was like an arrow went through my heart when our councilman said yes for Formosa.

We went to court three times, twice on Zoom. And Judge Trudy White was the judge. And then the last time we went in person, and then it was four months for her to come back with her decision. And Judge Trudy White is a thorough judge. She goes through every little sentence. And I like that about her.

And so she came back in September and gave us the ruling. And my lawyer called and said, “Sharon, have you heard the news?” I said, “No.” She said, “We won.” I said, “We won?” She said, “We won on all counts.” I said, “On all counts?” She said yes. I was so happy. I said, “Thank you, dear Lord. You said you were going to do it. Thank you. Thank you.” He did it. And Formosa is at the point where I think they are ashamed, because they have all this money and they lost. And we didn’t have any money. And we won.

When you go back to the Bible, you can read about how David won over Goliath. David shot that bow and arrow and Goliath fell. And so one time we sent out an article saying “Goliath is wobbling.” And the lawyer called and said “Sharon, that’s a good title.” Somebody wrote that for us. And she says, “Wobbling is almost down.” I said, “That’s right. It’s almost down.” And in September, it fell all the way down. Because David was so little. Goliath was so big. And we are small and industries are large. They have billions and trillions of dollars. The dignitaries, all of that’s for industry. The laws is in favor of industry, not to protect us. So it’s just like a David and Goliath fight. We are fighting a giant. Formosa is a giant. And just little people like us destroy this giant.

So we not going to celebrate until it’s completely down, because they are appealing it.

If RISE St. James and other organizations hadn’t stepped in, Formosa would be built. Not completely finished, but it would be started on already. And the pollutants would be triple the emissions in the Fifth District and doubled throughout the parish. It would be like 800 tons of greenhouse gases per year and it would be 14 plants inside of the complex. That’s how big it would be. The complex would be sitting on 2400 acres of land. And that’s a lot of land. And we have to pass by that industry every morning. Probably smell the stuff and they were going to dump more chemicals into our drinking water. So it would kill off our birds, our animals, and the people.

I think if you want to be successful in anything, you have to do it with the whole community. Not by yourself, but with people helping you and joining forces with you. The power’s in the people. And to be successful, you have to get your facts. You have to know what you’re fighting against and what the reasons are, the consequences. You have to know all of these things before you just step out there and be that voice. If nobody else is speaking up, you speak up. You be the voice. Do your homework. Talk to God, and you will be successful.

I feel like I’m doing what God want me to do. And sometime I pray and I ask God not to let me lose track of what he want me to do. Sometime I pray and I ask him to continue to guide me, because the devil gets in the way. And I mean people that try to come and help us for their own gain, not because we are being poisoned. They come. They help us to make money off of our lives. And I ask God not to let me hate them. And not to let me lose sight of what you told me to do. And I have to pray hard to keep the vision of what God gave me. It’s a hard fight, because you’re fighting people that’s fighting against you. But I’m not afraid. God put this in me. He gave me the strength, the knowledge, the courage. And the faith. And that’s what keeps me going.

What’s next for RISE St. James is to stay on top of what’s going on, to make sure we get it firsthand what industry is trying to come in. And as I speak, they have some right now that’s trying to come in. And so we want to try to get it first so we can stop it before the parish council approve it.

I want reparation for the family members who lost people due to industry and all the pollution. And I want the industries that are not following the rules and regulations, I want them to be shut down and moved away. And bring back our houses, our grocery stores, our post office, and bring us clean air. Clean air is the main thing and clean water, and be able to do a garden again and eat your vegetables from your garden. Butter beans, okra, tomatoes, cucumbers, squash. Oh, boy. That would be nice. And string beans. I would love that. I would like to see the Mississippi River clean and not full of chemicals. But my dream is to see St. James the way it was when I was a little girl. That’s what I would love.

Oh, my God. That’s the answer. That’s the key. Having faith, having God on your side. That’s the answer to anything that you want to do. And I mean, before I felt like this, it changed me. It changed my inner being. I look at people now. People that say something of the worst person. And I always say, there’s some good in that person. You just have to dig a little bit deeper. And the same way with my students, when some of the teachers didn’t want the students around them. And I said dear Lord, how could they think like that? That’s a human being. But now I see good in just about everybody, even the worstest person. I look at people in a deeper eye. Like a deeper eye. I just go deeper into their soul. I see things different in life. I see life different. And I feel like this is my mission to save the life of the people in St. James Parish and throughout Cancer Alley.

In March, RISE St. James, alongside other organizations, sued St. James Parish. They’re demanding a moratorium on the construction of new petrochemical plants. If successful, it would be the first ban of its kind in the state of Louisiana.

More reading on this topic:

- ‘Goliath is wobbling’: Louisiana court strikes blow to Formosa’s giant plastics plant

- EPA finally calls out racism in Louisiana’s Cancer Alley

- Cancer Alley campaigner wins Goldman Prize for environmental defenders

Credits:

Grist editors: Jess Stahl, Claire Thompson, Josh Kimelman | Design: Mia Torres | Production: Reasonable Volume | Producer: Christine Fennessy | Associate producer: Summer Thomad | Editors: Elise Hu, Rachel Swaby | Sound engineer: Mark Bush