After college, Michael Moritz got a job in Houston analyzing fatal car crashes. Moritz, a 27-year-old native of San Antonio, stood on Interstate 45, one of the most dangerous stretches of highway in the country, and documented how cars collided. One day in the fall of 2019, he learned that the Texas Department of Transportation, or TxDOT, intended to expand I-45, supposedly to fix congestion and make the highway safer. “More lanes just doesn’t equal safety,” he said. And then he learned about all the other negative impacts of the $7 billion expansion project, which would remake Houston’s downtown and demolish more than 1,000 homes, nearly 350 businesses, five churches, and two schools.

He got involved with a grassroots group called Stop TxDOT I-45 and started spending nights and weekends fighting the expansion. Gradually, he met people fighting freeway expansions across the state, including in the capital city of Austin, and joined a regular Zoom call to discuss strategy. He signed up for automated emails from TxDOT to find out when new projects were proposed and approved.

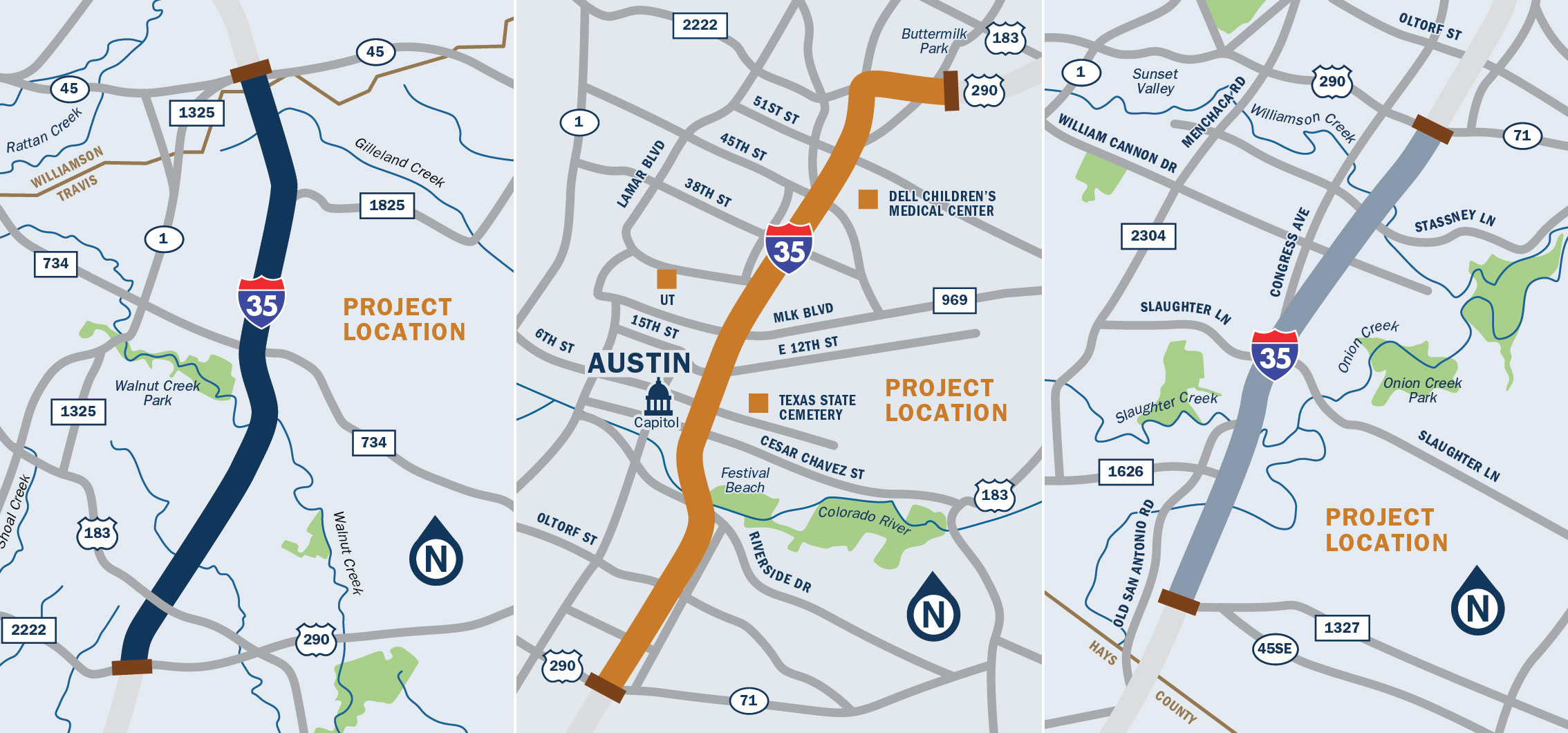

In 2021, just a few days before Christmas, he got two emails from TxDOT. The agency had issued a “finding of no significant impact” — or FONSI, pronounced like Fonzie, the Happy Days character — for two segments to a $6 billion project to rebuild and expand I-35, which passed through the heart of Austin. Really? he thought. No impact?

Moritz was alarmed by the idea that adding lanes to an interstate running through one of the fastest-growing cities in the country was considered to have no environmental impact. The expansion of the north and south segments of I-35 would consume 30 acres of land, affect more than a dozen streams and creeks, and add millions of metric tons of carbon to the atmosphere over the coming decades.

Moritz called up a few activists he knew in Austin. Together, they wondered: How often was TxDOT declaring that their projects had no impact on the human or natural environment? Moritz decided to find out. He searched TxDOT’s online archives for every environmental review published since 2015, as far back as TxDOT’s records extend.

Moritz quickly noticed that many projects that were physically connected had been spliced into segments, as I-35 was in Austin. Loop 88 in Lubbock, notably, had been evaluated in four segments stretching across 36 miles. Collectively, those segments would consume 2,000 acres of land, displace nearly 100 residences and 63 businesses, and cost almost $2 billion. And yet all four segments received findings of no significant impact, three on the same day.

Overall, between 2015 and 2022, Moritz discovered that 130 TxDOT projects were found to have no significant impact after an initial review, while only six received full environmental analyses detailing their impacts. Cumulatively, those 130 projects will consume nearly 12,000 acres of land, add more than 3,000 new lane miles to the state highway system, and displace 477 homes and 376 businesses. The total projected costs of those projects was nearly $24 billion, almost half of what TxDOT spent on transportation projects during that time and twice as much as the amount spent on projects that received full environmental reviews.

“It can’t be argued with a straight face that these big, multihundred-million-dollar projects don’t have significant impact,” says Dennis Grzezinski, an environmental lawyer in Wisconsin who has worked on NEPA cases for three decades and who was not involved in Moritz’s study. He called Moritz’s analysis “a giant red flag” that TxDOT was approving projects in violation of NEPA. “If TxDOT is producing environmental assessments that result in FONSIs over and over and over again, on large-scale interstates and major highway expansion projects, there is clearly something major that’s wrong and not in line with NEPA requirements,” he says.

Now, a group of activists is suing TxDOT, saying that the agency split the I-35 project into segments in order to obscure its full impacts and “circumvent” the requirements of NEPA. The case, filed in U.S. district court, raises larger questions about the federal government’s decision to give TxDOT the authority to approve its own environmental reviews.

“I think the words ‘no significant impact’ have meaning,” Grzezinski says.

Under the 1970 National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA, any state agency receiving federal funding for a project must document how the project impacts the human and natural environment. That documentation is categorized in one of three ways, depending on the project’s perceived impact. Actions that “significantly affect the environment” require a comprehensive environmental impact statement, which quantifies those impacts, includes specific ways the agency would mitigate them, and asks for significant public feedback. (The final environmental impact statement for the Houston highway expansion exceeded 8,000 pages.) On the other end of the spectrum, relatively minor projects — like repaving an existing road or repairing an interchange — can receive what’s called a categorical exclusion, essentially an exemption from NEPA. Everything in between is considered through an environmental assessment, a relatively concise document, typically a few hundred pages. An environmental assessment leads to either a full environmental review or a finding of no significant impact, which allows the agency to proceed with land acquisition and construction. But because NEPA covers a broad array of government actions, the law doesn’t define what makes an environmental or social impact “significant” — whether it’s acres of land taken or people displaced — and thus what triggers a full environmental review.

One of the people Moritz called in December was Adam Greenfield, the founder of a grassroots campaign called Rethink35, which called on the state to tear down I-35 in Austin, replace it with an urban boulevard, and reroute pass-through traffic around the city on existing roads. A longtime bicycle advocate, Greenfield had been galvanized into action when he saw TxDOT’s plan to expand I-35 from 12 to 20 lanes, including frontage roads, through central Austin, blocks from where he lived.

For Greenfield, that prospect felt like not just a neighborhood threat but also an existential one: Transportation is the leading source of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States, mostly due to passenger cars and trucks. TxDOT itself has found that vehicle emissions in Texas accounted for 0.48 percent of total worldwide carbon dioxide emissions, even as the state represents 0.38 percent of the world’s population. And more capacity for cars usually leads to more people driving, a phenomenon known as induced demand. According to a calculator developed by the Rocky Mountain Institute, a sustainability nonprofit, the entire I-35 project would generate 255 million to 382 million additional vehicle miles traveled per year, resulting in 1.2 to 2.6 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions by 2050, roughly equal to the annual greenhouse gases generated by a small coal-fired power plant.

Segmenting I-35 obfuscated the full impact of what TxDOT was trying to build, Greenfield says. In June, Greenfield’s Rethink35, along with the Texas Public Interest Research Group and Environment Texas, filed a lawsuit against TxDOT, alleging it had violated NEPA by splitting I-35 into three separate projects with distinct environmental reviews. “If you look at the proposals, it seems pretty obvious to us that this is one big project,” Greenfield says. “They’ve used a lesser environmental review, an environmental assessment, for the north and south portions. For such an important project with such enormous implications for the region, they should be doing a full environmental impact statement.”

Segmenting projects and issuing FONSIs is not a strategy unique to Texas, says Matt Casale, the director of environment campaigns for the U.S. Public Interest Research Group. “It’s widespread and it’s a problem.” But Texas, as well as seven other states including California, has little federal oversight. In 2012, the Federal Highway Administration, or FHWA — which oversees the construction and maintenance of highways — created a program that would allow state transportation departments to assume federal responsibility to enforce NEPA. The program, called NEPA assignment, allowed agencies like TxDOT to approve their own environmental reviews, with annual audits to ensure compliance. The program solved a capacity problem: At the time, TxDOT had more than 150 people working on environmental review, while the federal agency had a fraction of that. NEPA assignment would allow TxDOT to move more quickly on projects, reducing cost and unnecessary delays.

When TxDOT joined the program in 2014, it signed an agreement with FHWA, which was renewed in 2019. Last year, when FHWA intervened to stop the expansion of I-45 in Houston, citing concerns that the project would disproportionately impact Black and Hispanic communities in violation of the Civil Rights Act, it also alerted TxDOT that it would be reviewing the agency’s compliance with the agreement. Moritz thinks his findings should be included in that review. Last month, he emailed his analysis to FHWA and asked the agency to “consider the number, scale, and segmentation of projects TxDOT has determined to have no significant impact since the execution” of the agreement. FHWA declined to comment on Moritz’s report.

Splitting a large project into discrete parts, as TxDOT did for I-35, is not itself problematic. What makes segmentation illegal is when the act of splitting conceals the overall intent of a project, effectively hiding the forest in the trees. That’s what happened in San Antonio in the 1970s, shortly after NEPA was signed into law. For years, a local conservation group had been fighting a project called the San Antonio North Expressway. The proposed freeway would cut directly through Brackenridge Park, which straddles the San Antonio River and spans nearly 350 acres of parkland, wildlife habitat, and trails. Facing public opposition, the Texas Highway Department, as TxDOT was known until 1975, split the highway project into segments and requested federal approval for the two outer sections of the roadway, which stopped short on either end of the park. This appeared to all but guarantee that the central segment would bisect the park. After the outer segments were approved, the conservation group sued, saying the highway department had violated NEPA by illegally segmenting the project. Under NEPA, highway projects can advance in segments only if those segments begin and end at rational points, exist with “independent utility” from one another, and — importantly — don’t “restrict consideration of alternatives for other reasonably foreseeable transportation.”

A yearslong court battle ensued, eventually attracting the attention of the U.S. Supreme Court. “This case disturbs me greatly,” wrote Justice Hugo Black. “The two segments now approved stand like gun barrels pointing into the heartland of the park.”* The project was ultimately built after Texas declined to use federal money for it.

The plaintiffs in the I-35 case are now making the same argument, only this time the gun barrels are pointing into the city of Austin. The groups opposing the highway expansion say that TxDOT’s approval of the north and south segments restricts the agency from considering alternatives to expansion in the central segment — like the boulevard proposed by Rethink35, or a completely depressed and covered highway, an idea advanced by the nonprofit Reconnect Austin. “A highway … needs to be cohesive in order for traffic to flow and congestion be avoided,” they argue in the case filing.

That cohesion can now only be achieved by expanding the central portion of I-35, Greenfield says, even as TxDOT ostensibly considers alternatives as it progresses through a full environmental review for that segment. For example, the schematics for the I-35 north and south projects show TxDOT adding two to four managed lanes, basically express lanes for high-occupancy vehicles and transit, and in turn expanding the total number of lanes on the highway. But the whole purpose of an express lane is to move traffic through the city, not stop on either end of it, says David Adelman, an environmental law professor at the University of Texas at Austin who is not involved in the lawsuit against TxDOT. “So if you build an express lane in the north and south, you’re pretty much committing yourself not only to having express lanes through the city, but also expanding the number of lanes,” Adelman said. “And that’s directly impacting the options that you have available to you for the center part of the project,” he says.

TxDOT declined to respond to questions from Grist. But at a TxDOT planning conference in Houston in May, Anthony Horne, an environmental specialist at TxDOT’s environmental affairs division, explained to a crowd of TxDOT employees and consultants how the significance of a highway project is evaluated in context. “You kind of have to work the equation to try to figure out, is this something that is going to cause an issue? Are people concerned about it?” He described projects with “a couple of displacements” that didn’t undergo any environmental assessment. “Those people didn’t seem to be too concerned about it,” Horne said. “Therefore, because there was no sense of significance to it, we could proceed.”

Other TxDOT employees and consultants confirmed that the level of anticipated public controversy can be a determining factor when deciding between an environmental impact statement and an environmental assessment. That public outcry should determine which projects get full environmental reviews is fundamentally inequitable, said Kelly Haragan, who directs UT’s environmental law clinic and is not involved in the lawsuit. “A community that can gin up a whole lot of attention about a project is probably a community that has more resources and time.”

It is also circular logic, Adelman says. Public hearings can surface controversy, which is precisely the process an environmental assessment compresses. “There can be an interaction between the agency’s public process and the degree of public attention and salience to a particular decision,” Adelman says. “It can create perverse incentives on the part of agencies because if they’re worried about public attention, then they just want to get through the process as fast as they can. And if they can do that, then they can depress public attention, which just reinforces the determination that they’re making.” Indeed, the environmental assessment process for the north and south I-35 projects generated just over 800 public comments. In comparison, since 2020, more than 9,500 people have commented on the I-35 central project as it progresses through a full environmental review.

Now, a judge could require TxDOT to expose the entire project to that level of public scrutiny. There is precedent for the federal government to overturn a state department of transportation’s environmental assessment. Last year, FHWA approved a FONSI for an $800 million plan to expand I-5 through central Portland, Oregon — and then rescinded that approval after three community groups sued the federal agency, alleging that the state did not thoroughly study the impacts of the proposed expansion on the surrounding neighborhood.

Because NEPA is a procedural law, mandating the process that a public agency must follow rather than any particular outcome, there are limits to what lawsuits can accomplish. Even if the plaintiffs in the I-35 suit prevail and TxDOT is required to do a single environmental impact statement for the whole project, the agency isn’t obligated to choose an alternative with a lesser environmental impact. “It requires them to say, essentially, here are all the bad things that we’re going to do when we have these other alternatives that do less bad things, and forces those decisions to be made under the glare of public transparency and scrutiny,” Grzezinski says.

Moritz thinks TxDOT has lost the right to approve its own environmental reviews. Officials in Houston have told him that this oversight “takes up a lot of bandwidth for the feds and that they may be disinclined to revoke or not renew” NEPA assignment, he says. “And my response to that generally is: There’s levels of power and checks and balances for a reason. And a bandwidth constraint shouldn’t be determining the fate of the built environment in Texas.”

*Correction: This story originally misattributed a quote from a different judge to Justice Hugo Black.