The Art of Repeal

Illustrating Trump’s toxic legacy — and Biden’s daunting task ahead

Joe biden has a mess on his hands. He inherits a White House plagued by the specters of violence, distrust, racial animus, and an actual plague. Donald Trump was loud in many ways, from the tweets and the reality show-inspired unveilings of Supreme Court nominees to the audible whistles to white nationalists and the tantrum over last year’s election results. But amid his chaos and contradiction, his administration was dedicated to a quieter art: the regulatory rollback. If America was to be made great again, remnants of President Barack Obama’s era needed to be dismantled.

Obama had left behind an environmental legacy, however rushed and incomplete. The country had entered a historic climate agreement with 195 other countries. It had committed to curbing carbon emissions from coal plants and improving the fuel efficiency of new cars and trucks. The administration had conserved more than 550 million acres of land and had given the clean energy sector a $90-billion jumpstart via the 2009 Recovery Act.

So by the time Trump was sworn into office on January 20, 2017, there was much to undo. Trump’s Cabinet secretaries would direct particular ire toward Obama’s environmental and climate accomplishments.

In the four years that followed, the new administration made hundreds of attempts to dampen the U.S. government’s response to climate change and limit the scope and efficacy of federal oversight. Executive actions, judicial challenges, and new, industry-friendly rules streamed prolifically from the Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Interior, Department of Energy, and other agencies.

Some of the impacts of this assault on environmental protection won’t be felt for years. Others are already laid bare before us.

As the COVID-19 pandemic fanned across the United States last summer, researchers from American University reported that over a six-week period from March to May 2020, airborne particulate matter surged in many parts of the country. In March, the EPA had announced a freeze on the enforcement of environmental regulations as part of its response to the pandemic — and companies had taken advantage, with some heavily industrialized counties across the U.S. seeing air pollution rise around 13 percent relative to counties with few polluting sites.

Since COVID-19 is primarily a respiratory illness, an increase in particulate matter could pose an even greater risk to public health. In fact, the researchers estimated that in regions with more industrial sites known to release toxic substances into the air — like Harris County, Texas, which contains most of the Houston metro area — the spikes in pollution traced back to the freeze on enforcement were associated with a more than 50 percent increase in COVID-19 cases and more than a 10 percent rise in deaths when compared to areas with fewer such sites.

“These results are stronger for counties with higher fractions of Black individuals, suggesting that the burden of pollution exposure is unequal,” the authors wrote. “Pollution might have the largest impacts on the most vulnerable members of society who suffer from worse health, causing higher death rates and more severe cases of COVID-19.”

The legacy of the Trump administration's environmental deregulation won’t be relegated to the pages of the Federal Register. It will be written in bones.

Energy

From home heating to jet fuel, around 80 percent of the country’s emissions stem from the burning of oil and gas. The release of methane, the primary constituent in natural gas, stokes a hotter climate — methane is 84 times more potent than carbon dioxide over the course of 20 years. It’s a frighteningly powerful greenhouse gas that the Trump administration has made easier to emit.

Last August, the EPA eliminated all restrictions on methane emissions for new sources of the gas, like natural gas pipelines and new fracking sites, as well as removing the agency’s own ability to set methane standards for existing oil and gas facilities. That move followed a successful effort to get rid of methane rules on public lands. (The Trump administration also finalized a policy that will delay enforcement of emissions standards at municipal landfills that give off methane.)

The Rhodium Group, a private research firm, estimates that these rollbacks will result in the equivalent of 638 million metric tons of carbon dioxide entering the atmosphere through 2035, more than the annual emissions from the entire global aviation industry.

Some of the Trump administration’s most noteworthy rollbacks concern the production, processing, transmission, and storage of fossil fuels, but Americans will feel their impact in more ways than simply a warming climate. Loosening restrictions on carbon will often lead to greater releases of small particulate matter, air pollution responsible for the deaths of 200,000 people in the U.S. annually. More than a quarter of the country’s carbon emissions come from electricity generation, for example, and more than half of these electric-power emissions come from coal plants, a significant source of particulate matter.

In other words, climate policy not only works to cool the planet, it’s also a boon to public health. Consider the Obama administration’s signature piece of climate legislation, known as the Clean Power Plan, or CPP. It placed the first limits on carbon dioxide emissions from power plants. Penned under the authority of the Clean Air Act, the rule sought to cut the country’s carbon emissions from electricity generation to 32 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. Obama’s EPA estimated the reductions would prevent 90,000 asthma attacks in children by 2030 and thousands of premature deaths.

As the most symbolic of Obama’s climate efforts, the CPP was ripe for deregulatory backlash. In October 2017, speaking to Kentucky miners, Trump’s first EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt announced an end to what his boss had characterized as Obama’s “war on coal.” By June 2019, the administration had fully repealed the CPP.

Trump’s EPA itself noted the risks to public health. The move could over the next decade lead to more than 1,000 premature deaths every year. Each year there could be more than 17,000 cases of chest pain, wet coughs, wheezing, and other respiratory symptoms; 44,000 cases of exacerbated asthma; 31,000 missed days of school; up to 48,000 lost work days; and 290,000 restricted activity days (where someone spends more than half a day in bed or out of work).

The administration also finalized the CPP’s replacement — the Affordable Clean Energy Rule — which sought to soften regulations on power plants. But a day before Joe Biden was to take the oath of office, a federal appeals court struck down the ACE Rule, saying the EPA erred in its attempt to alter regulations on coal-fired power plants. Thus, rather than replacing Obama’s signature legislation, Trump’s EPA only succeeded in repealing it.

The Trump administration’s repeal of the Obama-era Clean Power Plan will, by the EPA’s own calculations, increase airborne pollution that will negatively affect people’s health and productivity …

…resulting in an estimated 48,000 lost work days and 290,000 restricted activity days, when workers lose half a day of productivity due to illness.

42 lost days

230 restricted activity days

To put those losses in perspective, consider people who work as respiratory therapists. They are responsible for deploying ventilators and assisting with intubations, both vital to managing the care of hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

There are 2,320 respiratory therapists working in New York City.

The productivity cost of repealing the Clean Power Plan is the equivalent of all of New York City’s respiratory therapists being off the job for four work weeks and then knocking off early for another 125 days.

Vehicles

In February 2017, one month after President Trump’s inauguration, the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers, the trade group that until recently lobbied on behalf of the auto industry, submitted a letter to Scott Pruitt. In it, the Auto Alliance urged Trump’s first EPA chief to withdraw the Obama administration’s recent guideline on fuel-economy and emissions standards for new cars and trucks, calling the previous president’s policy possibly “the single most important decision that EPA has made in recent history.”

A month later, the EPA and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration signaled their intention to grant the trade group’s request. By August 2018, the agencies had tossed out the Obama-era emissions standards — which aimed to set the average fuel economy for new cars and light trucks to an ambitious 54.5 miles per gallon by 2025 — and ushered in the Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient (SAFE) Vehicles Rule. It was finalized this past March.

The SAFE Vehicles Rule constitutes two rollbacks in one: It rescinds the state of California’s authority to set its own fuel-economy standards and weakens the federal rule that spelled out the national limits for model years 2021 to 2026. Altogether, the Rhodium Group estimates the new rule will result in more than a gigaton of carbon dioxide emissions through 2035, more than the yearly emissions of Germany.

In practice, the SAFE Vehicles Rule requires carmakers to raise fuel-economy standards across their fleets by 1.5 percent every year compared to 5 percent under Obama. To put the difference in context, relatively weaker fuel economy standards mean drivers wind up making more visits to the gas station. Analysts at the Environmental Defense Fund estimate that by 2040, Americans will spend an extra $244 billion on gasoline under Trump’s revised regulation. Add to that an extra $190 billion in heath-related costs due to higher levels of particulate pollution.

When compared to Obama’s more stringent fuel-economy standards, over the next 20 years, Trump’s SAFE Vehicles Rule will cost American drivers an extra $244 billion at the pump and $190 billion in health expenses stemming from the added pollution.

That’s a total of $434 billion.

Over the past 20 years, the federal government has allocated approximately $164 billion to the budget of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

So the cost to Americans from Trump’s vehicle rollbacks over 20 years will be two-and-a-half times greater than the amount of federal funding that has gone toward protecting the environment in the previous two decades.

Toxics

Under the twin pillars of the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act, the EPA is responsible for realizing President Trump’s frequently repeated vision of wanting the U.S. to have “the cleanest water, the cleanest air.” The administration’s record often finds itself working against that ideal.

A month into his tenure, the president signed an executive order calling for a review of the Clean Water Act’s definition of governable waters — the so-called Waters of the United States Rule. By 2019, the EPA had formally repealed it, and its replacement went into effect last June, lifting protections on more than half of wetlands nationwide.

The Trump administration also scrapped plans to ban chlorpyrifos, a neurotoxic insecticide that the Obama administration had teed up for prohibition. Trump’s EPA abandoned the legal theory and rewrote the cost-benefit analysis behind the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards Rule, which requires coal plants to limit their release of another neurotoxin, mercury, and is estimated to prevent up to 11,000 premature deaths annually. Further, the administration has also failed to ratify the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol — an international treaty signed in 1987 to phase out the use of planet-warming refrigerants called hydrofluorocarbons. In fact, it has pursued a strategy of actually deregulating the chemicals, which carry thousands of times the warming potential of carbon dioxide over a century.

The Clean Water Act, which has been on the books since 1972, was enacted to keep the country’s surface waters pristine. From the standpoint of water pollution, the greatest proportion of contaminants comes from wastewater released by steam-electric generating facilities, like coal-burning power plants, which create electricity by burning coal to boil water that in turn makes steam that spins a turbine to drive a generator. In 2015, the Obama administration put the first limits on the toxic metals that coal plants release through the effluent wastewater into rivers. The EPA estimated that every year the wastewater standards were in effect, up to 1.4 billion fewer pounds of lead, arsenic, mercury, selenium, and other toxic metals would end up in U.S. waters.

In 2018, the Trump administration suspended the rule and designed its own. Under the previous standard, coal plants would have had until the end of 2023 to come into full compliance. Now, they won’t need to do so until the end of 2025 — and fewer types of waste will be regulated.

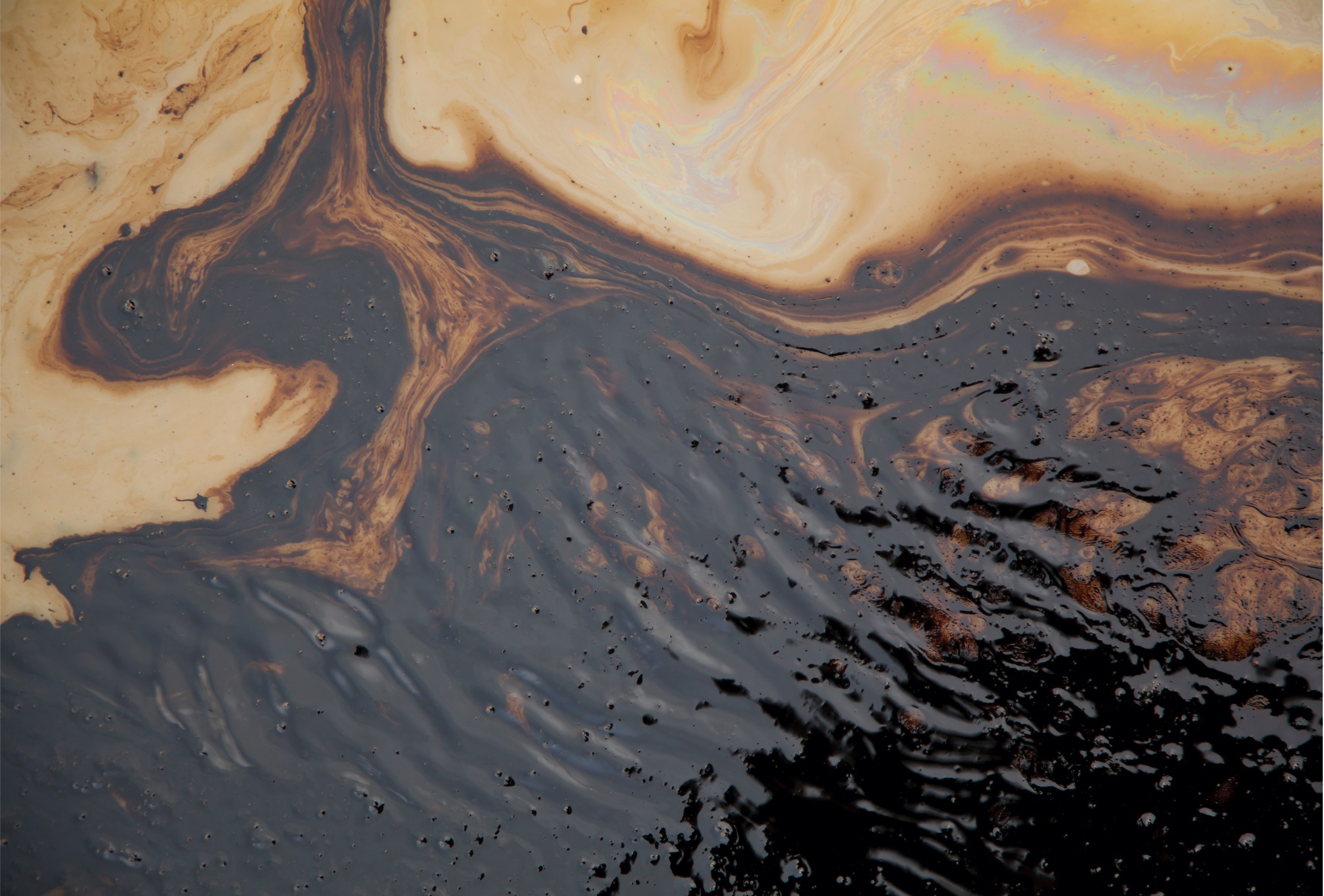

Under Trump’s new effluent rule, wastewater from facilities like coal plants will carry at least 1 billion pounds of contaminants — including mercury, arsenic, and lead — into rivers and streams annually.

Imagine these pollutants were oil. Taken together, the volume would amount to approximately 136 million gallons of petroleum each year.

By comparison, the Deepwater Horizon spill — the largest oil spill in U.S. history — resulted in 134 million gallons of oil leaking into the Gulf of Mexico.

2018

Thus, we might say the rollback is akin to unleashing a Deepwater Horizon’s worth of pollutants into American rivers and streams every year.

Extraction

The Trump administration started its first year with a flurry of executive actions, many emphasizing oil and gas and bearing names like “Promoting Energy Independence and Economic Growth” and “Implementing an America-First Offshore Energy Strategy.”

The orders, combined with a move that December to shrink the boundaries of major national monuments (Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears in Utah), signaled that public lands were open for business.

“I’m a real-estate developer,” said President Trump at the Bears Ears announcement. “When they start talking about millions of acres, I say, say it again? That’s a lot.”

Over the course of four years, the administration went on to open Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge for oil and gas exploration and huge swathes of the Tongass National Forest, also a part of the Last Frontier, to logging.

The Center for American Progress recently tallied up all these moves and calculated that Trump had stripped federal protections from nearly 35 million acres of public lands. He had also reversed a trend that had emerged over the course of the previous decade, during which public land was increasingly made off-limits to the oil and gas industry. While annual federal acreage leased for oil and gas development fell 70 percent between 2009 and 2016, it rose by more than 115 percent between 2016 and 2018. And by the end of 2019, the United States became a net exporter of crude oil for the first time since the 1940s.

According to the Bureau of Land Management and the Center for Western Priorities, over the past four years, the Trump administration has brought at least 26 million acres of land to auction for oil and gas development, more than 20 percent (6.1 million acres) of which it ultimately leased to businesses.

How big an area has Trump opened for exploration? Consider California’s 2020 wildfire season, one of the worst on record, …

… with more than 4 million acres burned throughout the state.

Since 2017, 6.1 million acres have been leased for oil and gas development out of a total of 26 million that have been made available (a quarter of the total area of California).

Oversight

Under the Trump administration, it’s safe to say the EPA took a more hands-off approach. In 2018, the EPA conducted 10,612 inspections and evaluations of corporate polluters — down from 20,030 ten years earlier. The EPA workforce is currently the smallest it has been since the Reagan administration, more than 30 years ago. But the diminishing role of environmental protection echoes through more halls than the agency’s alone.

While the administration’s big-ticket environmental rollbacks have undeniable consequences, most of the damage comes from dozens of tiny cuts: disbanded working groups, revised formulas for determining the costs of pollution, rescinded policies that had once triggered environmental reviews, destroyed staff morale, and much more.

The crafting of rules simply looks different in 2021: It’s easier to justify policies and infrastructure projects that are less climate-friendly. In agency decision-making, for example, methane used to be priced at $1,400 per ton, once all its health and environmental effects were priced in. Under Trump, it dropped to $55 per ton. Trump’s “Energy Independence” order nixed the group that sets these guidelines altogether.

The administration has also proposed requiring EPA rulemaking to draw exclusively from studies that make their data publicly available. But as the editors of major scientific journals wrote in 2018, data are sometimes withheld from studies for privacy concerns. “It does not strengthen policies based on scientific evidence to limit the scientific evidence that can inform them,” the editors wrote.

New Clean Water Act guidelines now impose a one-year timeline for states and tribes to accept or reject proposed pipeline projects (and limit their review to include only impacts on water quality). And as a crown jewel to environmental deregulation, the Trump administration has also revised the implementation guidelines of the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA, for the first time since 1978. NEPA dictates that all federal agencies must consider environmental effects when proposing major federal projects. Under the new rule, agencies are no longer required to consider the effects of climate change, and fewer proposed projects fall under the law’s jurisdiction — removing a key federal protection for vulnerable communities that already suffer from burdensome pollution.

THE TRUMP ADMINISTRATION'S ENVIRONMENTAL ROLLBACKS

Filter the chart by clicking on the legend entries

With an incoming president who has pledged to put climate action at the center of his presidency and whose party controls both chambers of Congress, some of Trump’s rollbacks are likely to themselves be rolled back, and quickly.

But much of the work toward implementing federal climate solutions will be difficult. Not everything can be accomplished by executive fiat, and crafting new rules takes years. The sheer volume of work that requires the new administration’s attention poses another challenge to its environmental agenda. The Trump legacy runs deep.

And the legacy continues to be written during the lame-duck period. Last month, the Trump administration finalized its rewriting of the MATS Rule. Now, in practice, the cost-benefit analysis employed in future Clean Air Act rulemaking only focuses on the primary pollutant a rule targets — gone are the days that the slashing of airborne particulate matter that accompanies regulations to carbon emissions are factored in as a bonus. And despite growing evidence linking air pollution and coronavirus death rates, the administration also declined to strengthen an Obama-era regulation that capped industrial soot pollution. Staff scientists had recently shown that lowering the cap by 25 percent would prevent more than 12,000 deaths a year.

West Virginia’s deputy attorney general praised Trump late last year for not beefing up the soot standards, calling the administration’s leadership “reasonable and understanding.” “If they had been tightening it could have been a huge blow to the coal industry,” he told the New York Times.

It’s in this final push of environmental deregulation that we see the administration’s calculus in full relief, and it’s difficult to read it as anything other than providing succor for threatened industries by stealing more breath from the public. Not that government agencies are allowed to measure that kind of thing anymore — at least not until we’re led by an administration that’s less reasonable and understanding.