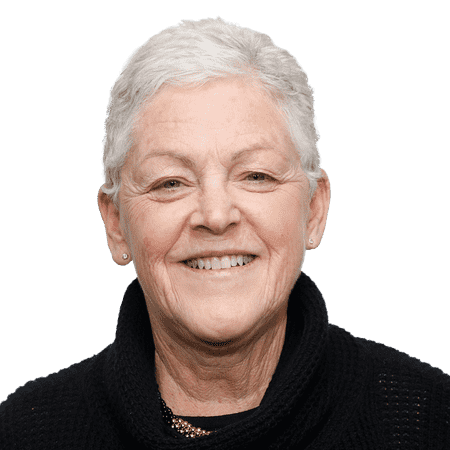

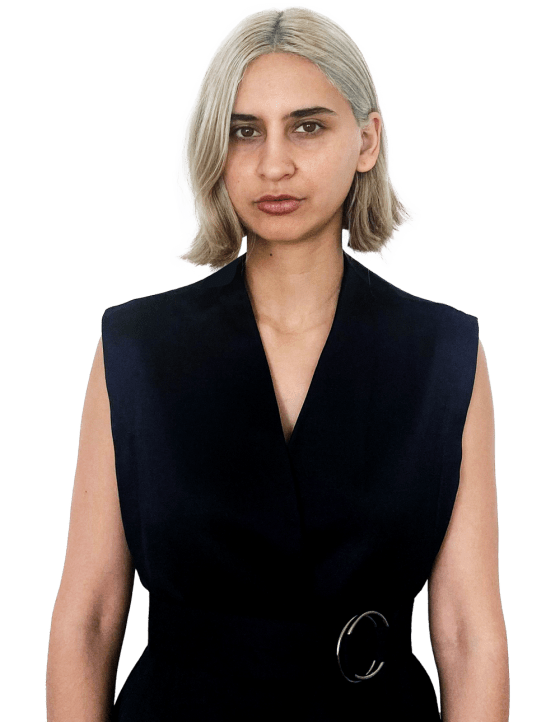

Faith E. Briggs

Documentary Filmmaker

Portland, OR

This filmmaker puts equity into the picture

While working as a camp counselor, Faith Briggs learned a lot about city kids and the influence that the media has over their lives. She vowed to create images that could foster confidence and a sense of belonging. As an avid trail runner, she saw how decisions about public land often leave out Black and brown communities. Those threads came together in This Land, the 2020 documentary in which she ran 150 miles through national monuments in the West. She combines scenes of stunning beauty with reflections on race, conservation, and equity. “My work has always been about representation, widening the spectrum of what’s available to believe in,” she says.

In her new podcast, The Trail Ahead, she and fellow runner Addie Thompson keep this conversation going — including some interviews with Grist Fixers. In order to thrive, she says, the conservation movement must actively recruit a greater variety of people. “If you think a community isn’t interested,” Briggs says, “they just haven’t been invited.”

Photo: Kenny Hamlett

“

“

“Nyeisha Mallet gives us all a good reason to feel optimistic about the future.” — Regina Hall, actress

“Nyeisha Mallet gives us all a good reason to feel optimistic about the future.” — Regina Hall, actress