Ahkim Alexis grew up in the Caribbean nation of Trinidad and Tobago, a place facing acute impacts of climate change. He is a curious and passionate writer by nature, and his firsthand experience with rising seas, eroding beaches, torrential downpours, and dwindling fresh water has become every bit as important to his stories as his heritage.

Both of those things shape “The Lexicographer and One Tree Island,” a finalist in Fix’s annual Imagine 2200 climate-fiction short story contest. The tale marked something of a diversion for Alexis, as it is both hopeful and steeped in the culture of his homeland — something he concedes he’s failed to convey in past work. Upon hearing of the contest, he reflected on the ways he’s seen climate change shape his homeland and decided to craft a narrative about hope that celebrates his native language. “Writers shouldn’t run away from their own culture,” he says. Rather, he says, they should embrace it and intertwine pieces of themselves in their writing to make it come alive.

“It’s very, very hard to exhibit one’s culture when you’re not speaking to or from it,” he says.

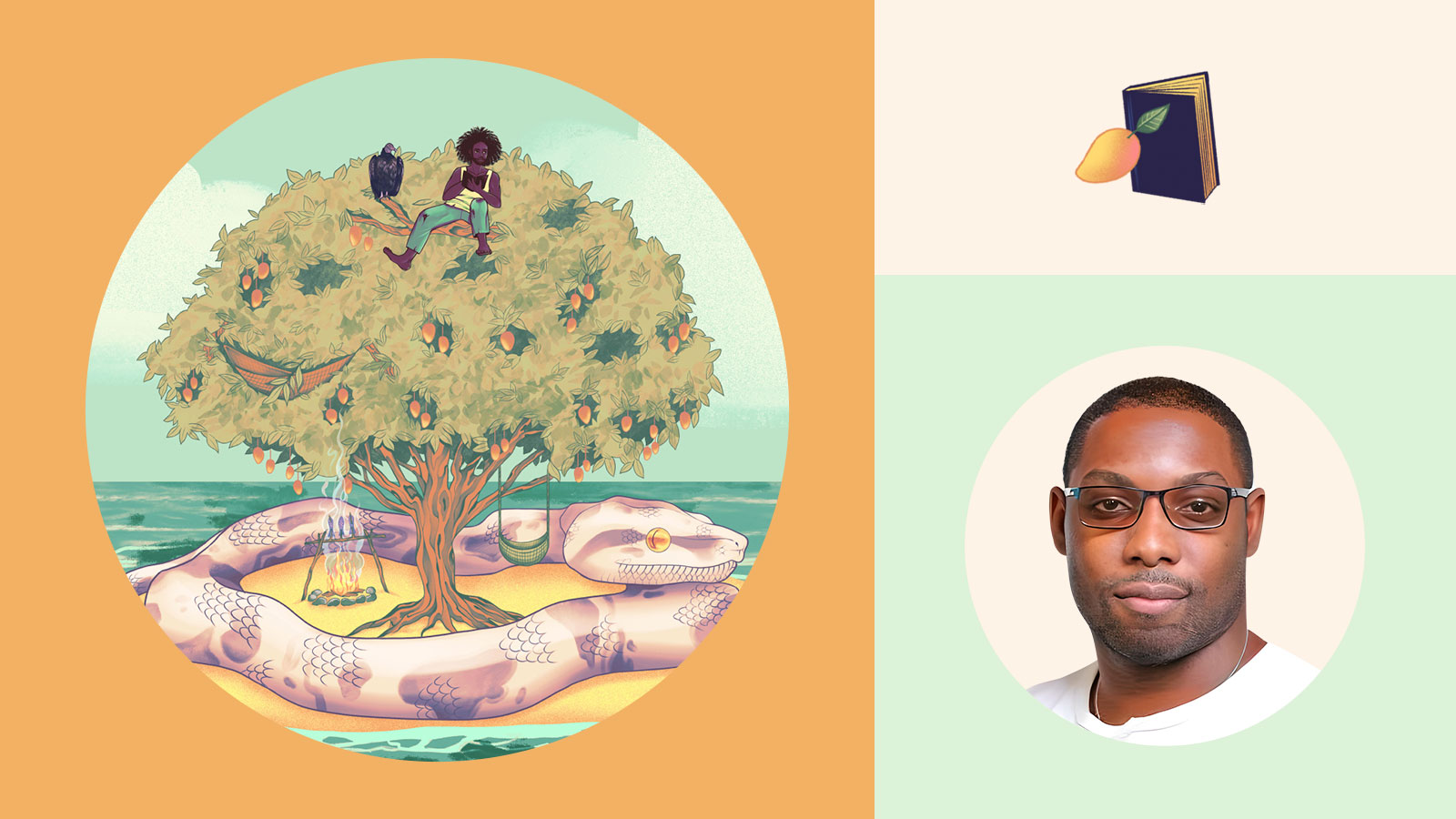

The lexicographer in the story is a young man left on the “last touchstone of the Caribbean,” which he shares with a single tree, after climate events diminished the land. Between visits from a bird and a snake, the protagonist fills his days stuffing his notebook with words from his native tongue, resolved to document a language that otherwise would die with him. Consumed with love for the land that’s left and hope for his future people, he rejects the “life-saving” modernity that could end his isolation, and in doing so rejects the cycle of history’s repeated mistakes.

[Read “The Lexicographer and One Tree Island,” a cli-fi short story by Akhim Alexis]

When Alexis writes a story, he typically maps out the beginning and the end. But when he started “The Lexicographer and One Tree Island,” he simply dove in, following his inspiration as the story came together in sequence. Alexis found himself drawing from Caribbean folklore and crafting an optimistic perspective for the future, even in the face of catastrophe and destruction.

Imagine 2200 creative manager Tory Stephens recently talked to Alexis on Instagram Live (Watch the full conversation on Grist’s Instagram) about his storytelling process, bridging the divide between humans and nature, and where he sees climate fiction taking him in the future. Their conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. You’re from Trinidad and Tobago, a small, dual-island nation and a frontline community. I want to start by asking you to discuss the importance of having folks living on the front lines writing climate fiction.

A. That is one of the only ways we can get our voices across. I think that fiction has always been a really potent way to get messages across to people who may not necessarily have listened to us. Politics is also important, but politics can only do so much.

Q. Your story is set on an island. Do you feel like you’re drawing on experiences you’ve lived through for this story?

A. Well, it’s fiction, and mostly fantasy. [But] I am drawing from experience to an extent, especially when it comes to the dialogue. The way people react to what’s happening in the story, like when the seas rise, was from experience. I think the corbeaux, the animals [in the story] tend to be much more representative of people I would have interacted with or things I think may happen — future ideas, I suppose. But the whole concept of the story, especially when it comes to the rising sea levels and erosion of the island, is based on my experience in Trinidad.

Q. A focus point of Imagine 2200 is stories centered on culture. That really came through with your story — I felt like I was there on the island, living the experiences. If someone wants to add culture in a powerful way to a story, how do they go about doing that?

A. Writers shouldn’t try to run away from their own culture. Start with language. Language is what I enjoyed most in my story. I think that’s why you see my use of language as very direct and the lead character, Lexicographer, centering language.

If you want to ensure that your story is culturally poignant, you definitely need to fall back on what you understand of your native language or the native language of the culture you’re trying to help represent. I could have written the story in standard English, and I have before, but felt like I failed. It’s very, very hard to exhibit one culture when you’re not speaking to or from it.

Q. When you found out about the Imagine 2200 contest, what moved you to write a story?

A. Hope. That’s what moved me to write a story, because I will say from my experience it is a challenge. A lot of stories don’t end hopefully because I think that, in today’s society, it’s a challenge to even come up with a hopeful solution, something that isn’t necessarily dystopian. The idea of writing something hopeful, even in the face of destruction and catastrophe, is a challenge for me. So I said, “I’m going to do it and it’s going to be tough,” because it calls for you to rework your narrative sensitivities. But you have to imagine a future that leaves room for success, even if it’s on a small scale.

“The idea of writing something hopeful, even in the face of destruction and catastrophe, is a challenge for me.”

— Imagine 2200 finalist Akhim Alexis

Q. A few stories in the collection, including yours, feel like they’re drawing from folktales or a place in their culture, or use the craft of folktales to tell a story.

A. In the Caribbean, in Trinidad and Tobago, folktales are a huge part of the culture. It’s something that is all around me. However, when I started writing, I ignored them. I felt, “I’m not going to write anything about folktales because they’re too mythical.” Strangely enough, when I started attempting to look toward a hopeful future in my writing, I looked back toward the folktales and the supernatural. So it’s very interesting the way culture comes back to mind. It not only pulls from culture, it pulls from religion and values and norms — things that will help us if you’re willing to look for something hopeful.

Q. What are your suggestions to aspiring writers for developing a story?

A. Definitely the first would be to read, read, read. Read a lot. I do more reading than I do writing. I think it shows when you don’t read a lot. [Reading] helps you with dialogue, helps you describe faces, things, animals. It helps voice, it helps the way in which you perceive [things] around you, and it helps you recognize things that you don’t want to. Editing heavily also helps. I try to edit as much as I can, and when I feel like I can’t edit anymore, I’ll send it to a trusted reader to tell me what they think and what they draw from it. Somebody who isn’t a writer sees a story differently than someone who is.

Q. What’s next for you? Are you going to keep moving toward hopeful climate futures, or go back to something dystopian?

A. I will say a mix. I have new interests in hopeful futures and climate fiction, so I definitely think I will write more stories or expand this story. I have interests in a lot of types of stories. I recently wrote a historical story based on a group of marginalized people in Trinidad who walk around naked, and it ends very sadly. I have a number of interests all over the place and climate fiction was added to them.