Anna Santo is a Ph.D. student at the University of British Columbia who has studied private landowners’ attitudes toward beavers in South America. Kai Chan is a professor and interdisciplinary sustainability scientist at the University of British Columbia.

April 7 is International Beaver Day, and lest you think these critters don’t deserve such an honor, you probably don’t know that they are, in fact, one of our best natural defenses against the warming effects of climate change.

As wildfire season approaches in the west, the North American beaver is an unlikely ally, one uniquely equipped to fight fires and store water.

As many as 400 million beavers populated North American landscapes before they were hunted to near extinction in the late 1800s for their furs. Today, beaver populations are rebounding, and there is increasing evidence that landscapes with beavers are more resilient to fire, drought, and extreme weather. Beaver restoration is a cost-effective, nature-based way to protect people and adapt to climate change.

Restoring beavers isn’t a new idea; programs like the Tulalip Tribes’ Beaver Project, Methow Beaver Project, and the Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife’s beaver relocation pilot project transfer “nuisance” beavers from urban or suburban areas to hydrologically impaired watersheds. Similar programs have successfully returned beavers to ecosystems across the United States and Europe.

It’s time to scale up this work.

Beavers are nature’s firefighters. They work tirelessly to cut trees, store wood in fire-resistant dams, and create ponds that act as natural fire breaks and provide refuge for wildlife during mega-fires. Federal land management agencies alone budget nearly $1 billion dollars for wildfire management each year to do much of the same: thin overgrown forests, dispose of cut trees (so they don’t add fuel to fires), and create open areas that slow fires down. Beavers do all this for free.

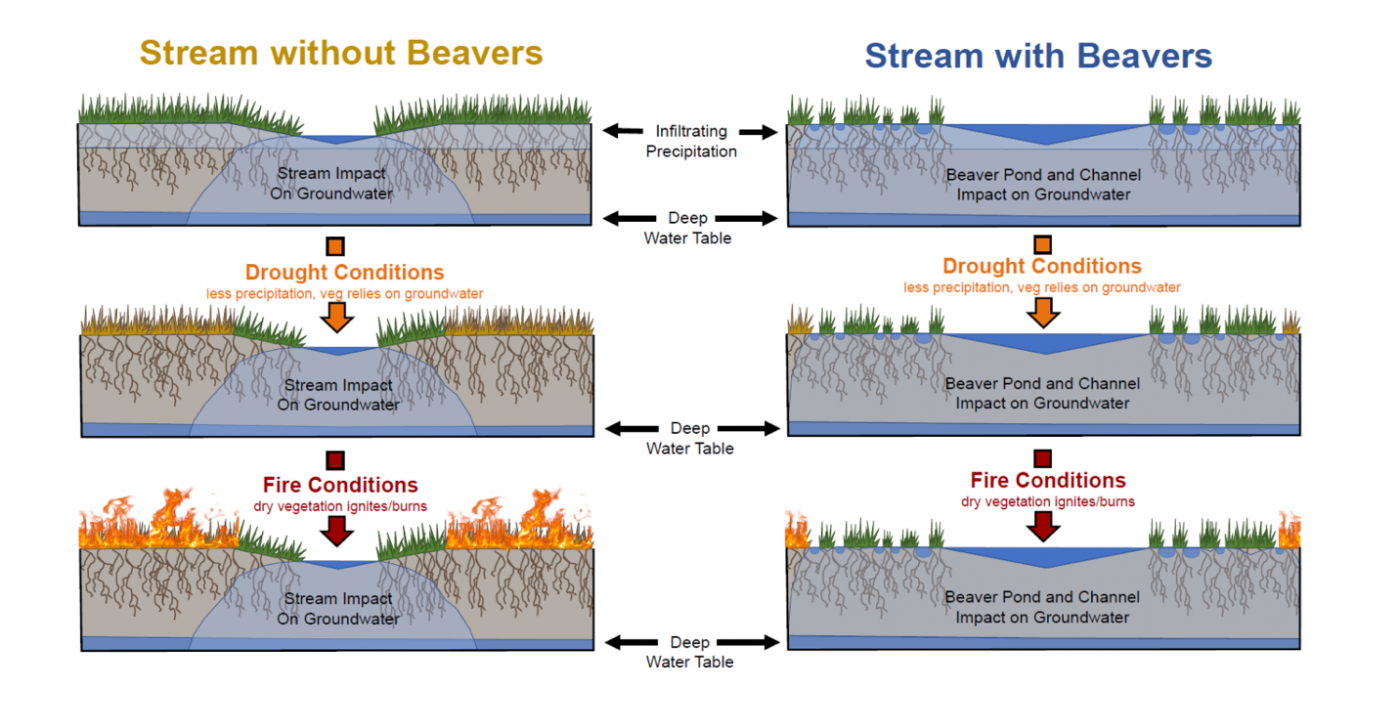

Beaver dams also help store water above and below ground, mitigating the impacts of climate change. As temperatures rise, more winter precipitation is falling as rain rather than snow. This results in diminished snowpack and glaciers, more extreme flooding and drought, and higher stream temperatures, especially in the summer. Beaver dams and wetlands release water slowly, helping to recharge groundwater. Not only does this increase the available water in increasingly hot, dry summer months, it helps filter water so that it’s cleaner and cooler.

Beavers also improve habitats for salmon, which rely on deep, cold pools of water, woody debris for cover from predators, and rest from fast currents. Salmon also need protected patches of gravel where they can lay their eggs. Beaver dams create pools of respite with plenty of wood cover for both juvenile and adult salmon. Dams also trap fine sediment, preventing it from smothering underwater nests of salmon eggs, while periodic dam breaches help maintain gravel patches. Ponds also provide nutrient- and insect-rich habitats where young salmon and other wildlife thrive.

To scale up beaver restoration, state and federal agencies first need to coordinate their beaver management efforts. For example, many state wildlife agencies allow beavers to be legally trapped on public lands in the exact places where state and federal agencies, nonprofits, scientists, and other partners are restoring them for ecological benefits. These goals are in direct conflict, especially when public funds pay for beaver restoration.

Trappers can be important beaver allies because their hobby or livelihood depends on maintaining healthy beaver populations. They shouldn’t be banned outright, but they should be limited from trapping within drainages where beavers are being re-established.

Private landowners and public land managers also need education: Beavers don’t always make the best neighbors — they sometimes flood roads, houses, or pastures, or they may chew infrastructure like trees or fences — so landowners will turn to lethal traps. States, counties, and towns that manage roads and culverts need guidance as well: Public road management is one of the leading causes of beaver deaths in the United States. The mission of the Department of Agriculture’s Wildlife Service is to resolve wildlife conflicts to allow people and animals to coexist; they are under a directive to use non-lethal methods when “practical and effective,” yet the agency killed more than 25,000 beavers in 2020.

Slaughtering all of these beavers doesn’t make ecological or economic sense. New beavers will likely colonize the very areas where they were trapped, and we have better tools that are a fraction of the cost of lethal trapping: Flow devices, sometimes called “beaver deceivers,” and pond levelers are specially designed fences and pipes that maintain streamflow when beavers start building dams. Physical barriers can also protect trees or other infrastructure that beavers may chew.

Given the vast contributions that beavers freely offer, we should be able to co-exist. Public funds could be used to offset the costs for private landowners to install beaver-friendly devices. State and federal agencies and private organizations often do this when other species like wolves and grizzly bears damage private property, and some organizations do the same for beavers.

To really build community with our semiaquatic rodent neighbors, we should help get them settled in new homes. Beavers that are captured and relocated often get sick or eaten by predators, but we can build them a safe place to arrive. Beaver dam analogs are human-made structures that mimic dams and are one of the fastest-growing stream restoration techniques in the western United States. Think of them as starter homes: They are inexpensive to build, they’re great for stream health, and they help beavers recolonize an area by providing temporary protection from predators while they build their dream dams, which they continue making bigger and stronger and more numerous over time.

If you’re a beaver believer, consider connecting with your local beaver advocacy organization, like the Beaver Institute or Beavers Northwest (there are many similar organizations across the country). If you have suitable habitat on your property, you may be able to request a beaver from your state wildlife agency. If you’re having trouble with a beaver, there are professionals who can install beaver deceivers or relocate the animals.

The rest of us need to lift up this animal with state wildlife agencies, elected officials, and friends and family. Our watersheds need them.

The views expressed here reflect those of the author. Fix is committed to publishing a diversity of voices. Got a bold idea or fresh news analysis? Submit your op-ed draft, along with a note about who you are, to fix@grist.org.

Correction: An earlier version of this essay misidentified the agency responsible for Washington State’s beaver relocation pilot program. The program is through the Department of Fish and Wildlife, not the Department of Natural Resources.