The vision

“When we fight pipelines, when we fight oil projects, when we fight all of the extractive development that harms our mother, we don’t do that just for ourselves. We do that so we can all actually have an earth to live on in the future. So that future generations that aren’t even born yet have an earth to come to.”

— Krystal Two Bulls, landback campaign director at NDN Collective

The spotlight

For some Indigenous leaders, 2022 feels like a turning point. Awareness has grown in the climate movement and beyond that a healthy and livable future on this planet depends on understanding and valuing traditional knowledge about how to care for it — and that the keepers of that knowledge need to be at the head of the table.

In North America, First Peoples managed ecosystems for over 20,000 years before white settlers arrived and brought with them industrialization and extractive economies. Today, Indigenous people make up less than 5 percent of the world’s population, but support 80 percent of its biodiversity.

Last fall, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and the Council on Environmental Quality issued a joint memo stating that Indigenous ecological knowledge should inform federal policymaking, and together committed to developing government-wide guidance on how to engage with tribes and elevate traditional knowledge. That’s one small step, and one example of how the climate movement, at all levels, is waking up to the need for Indigenous leadership.

“What we’re saying is, don’t create places for us in your white supremacist structures,” says Nick Tilsen, president and CEO of the Indigenous advocacy organization NDN Collective. “We actually want to create our own systems founded in Indigenous values.”

For non-Indigenous folks in the movement, that means elevating Native voices, supporting efforts like food sovereignty and resistance to fossil fuel development, and embracing a goal that advocates say is critical for achieving climate and racial justice: getting Native lands back into Native hands, aka the landback movement.

As part of Fix’s 22 Predictions for 2022, a handful of leaders shared the ways in which they see Indigenous power and leadership moving to the forefront of climate action in the next year.

Neftalí Durán, an Indigenous chef and cofounder of I-Collective, pointed out why centering Indigenous knowledge is is crucial:

“We need to think of growing food as a concept that the Indigenous people have been figuring out for thousands of years and will continue to. Indigenous values and Indigenous leadership is what we need to look at for all aspects of climate change, whether it’s growing food, keeping companies in check, preventing mining in Mexico and South America, or defending the Amazon forest.”

For Tara Houska, a tribal attorney and founder of Giniw Collective, the urgency of the climate crisis feels like a tipping point that will make this a reality:

“The amount of movement that’s happening around the globe when it comes to land defense strategies, when it comes to divestment, when it comes to these really effective methods of change — I see that growing. I see a generation of concerned people who recognize that the climate crisis is not something you can mitigate, it’s not something that’s negotiable, it’s not something that is conceptual. The climate crisis is very real.”

Nick Tilsen, president and CEO of NDN Collective, went even further to predict that power is going to radically shift in 2022:

“The landback movement is going to change conservation forever. There’s justice to be had in a mostly male, white-led conservation world. Many Indigenous peoples’ lands are currently under conservation easements that they don’t have access to for cultural purposes, for spiritual purposes, for subsistence purposes, for self-governance purposes. I think you’ll see the Indigenous peoples’ struggle and the climate struggle and the landback movement put pressure on not only the world of conservation, but those who fund it. And that will lead to some of the biggest Indigenous-led conservation deals in history in the next 12 to 36 months.”

This type of shift would represent the fruits of hundreds of years of work. Simply put, landback is a reparations movement that has existed since colonization. Its goal is the physical return of land to Indigenous peoples — and the return of all things that depend on connection to the land. [Check out our explainer on landback and what it means to various leaders.]

“We were fully thriving economies and societies and communities, pre-colonization,” says Krystal Two Bulls, director of the landback campaign launched a little over a year ago by NDN Collective. “We had trade networks, we had food and housing, education, healthcare. We had kinship, we had governance models, our languages, our ceremonies, our culture.”

Landback is about the revitalization of all of those things, and ultimately it’s a solution that advocates say will benefit everyone. Nick Tilsen emphasizes that returning land to Indigenous stewardship will lead to more fossil fuels being kept in the ground and a fusion of Western science with traditional ecological knowledge that will keep ecosystems and sacred places pristine.

One of the challenges of the movement, he says, is that it can make some people fearful. “At first people are going to be like, ‘Oh my God, the Indians are getting their land back — run for the hills, everybody!’ And then they’re going to be like, ‘Oh my God, they’re doing a pretty good job.’”

Two Bulls believes that opposition to landback and what it will mean for the descendants of settlers comes from a place of guilt. “Your fear is rooted in the fact that you think, when we get our land back, we will treat you the way that you have treated us.”

Replicating systems of oppression has never been part of the plan — and proponents of the movement say that to continue accelerating the work in 2022, they could use some help from white people in dispelling that knee-jerk fear. “A lot of our allies and accomplices could play a really important role in helping lead some of those conversations,” Tilsen says, “so that we, as Indigenous people, can focus on getting our damn land back.”

[Read more about landback and other trends for the coming year in Fix’s new What’s Next Issue.]

More exposure

- Read: a chronicle of landback victories in Australia (Atmos)

- Read: a landback FAQ for settlers in Canada and beyond (Briarpatch Magazine)

- Read: a feature on some of the leaders and teachers working to revitalize Indigenous knowledge systems (Fix)

- Watch: a short film about the birth of NDN Collective’s landback campaign, catalyzed by a demonstration at Mount Rushmore in July 2020 (NDN Collective)

- Watch: The 2020 documentary Gather explores the idea of Native sovereignty through the lens of food (available on Netflix)

- Listen: The Red Nation Podcast is a great resource for thought-provoking discussions on Indigenous history, politics, activism, and culture

See for yourself

Most issues of Looking Forward begin with a drabble — a 100-word piece of fiction — that offers a vision of the just climate future we want to see. Some of y’all have been sending in your own visions, and they’re too good not to share.

Huge thanks to the writers who contributed these drabbles! (Want to try out your own drabbling skills? Please share with us.)

“300 fruit trees. All alive and healthy,” she typed just before her mother interrupted to ask about the schedule at school tomorrow.

“We filed an absence request. We need to work on the final presentation for our Generation’s Mission,” she replied, and finished typing: “date of check: May 14th, 2053.”

She knew her mother always wanted to hear more, because back in her day you had homework to do, you did not engage on a mission to shorten the supply chain.

“Our entire neighborhood is now self-sufficient, fruit-wise. Fifth year in a row. We did it. Our generation did it.”

— by Anca Stănescu

We cross the street, over the permeable-paver bikeway, and duck into Lucas’s kitchen. At least the haze held off today.

“Wow, everything smells amazing!” I exclaim.

Turning back from the solar-powered stove, Lucas smiles and shouts, “Thanks!” as I swoon over maple-glazed brussels sprouts. Somehow, it’s never the same menu — just whatever was fresh from the day before.

Alli throws open the rented kitchen’s window, revealing a cluster of folks already outside with their ceramic containers. I tie my apron around my waist and wave excitedly out the window. Sunday mornings just aren’t the same without community.

“Let’s get serving!”

— by Bethany N. Bella

They make another venture out of the underground nest onto a forest floor teeming with the colorful flora and fauna of the tropics. These ants on a foraging mission don’t number very many, their tiny, dark bodies inconspicuous.

Years ago, the forest was an abandoned field. Its soil couldn’t support the hardiest of crops. Ants ventured, as they do, into the field. They built nests, foraged, defecated, and laid their dead to rest, all in the soil. They started something.

The foragers carry on, with only their mission in mind. They don’t know it, but they are agents of rebirth.

— by Anika Hazra

On our horizon

- What’s Next: Today, Fix published our latest digital exploration — a look at what’s next for climate and justice solutions in the year ahead. Dive into the stories here.

- Fix Live: Want to explore more themes from our What’s Next Issue? On January 19, we’ll gather a roundtable of climate and justice leaders to talk about the changes they see coming in tech, infrastructure, food, energy, and culture in 2022. Register here to join in on the conversation.

A parting shot

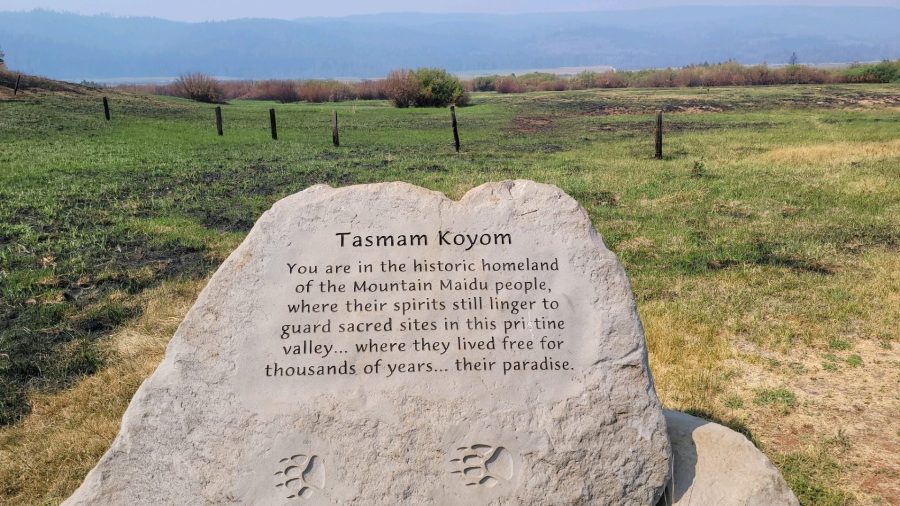

Tásmam Koyóm — dubbed Humbug Valley by European settlers — is a 2,325-acre parcel of land in Northern California that was previously owned by Pacific Gas and Electric. The valley was returned to the Mountain Maidu people in 2019, as their first landholding since colonization. Read more about the historic transfer here.