Gabriel Dunsmith, a writer, holds a degree in environmental studies from Vassar College and lives in Reykjavík, Iceland.

In the spring of 2014, I sat at the back of the Supreme Court as the justices heard arguments in CTS Corp. v. Waldburger, the ramifications of which would touch some of the most contaminated sites in the country. The lawyer for the company that had polluted my hometown of Asheville, North Carolina, argued that his client bore no responsibility for the rash of cancers, including my own, that plagued the area surrounding its factory.

Chief Justice John Roberts seemed intent upon the attorney’s line of reasoning, as did many other justices. But Ruth Bader Ginsburg, barely visible above the bench, had shrewd questions for the attorney. The other justices sat up straighter when she spoke. Yet I had the sinking feeling the cards were stacked against us and walked out of the Supreme Court that day with a pit in my stomach.

The rest was a blur: I met Erin Brockovich on the steps outside, hugged my parents goodbye, and boarded the bus back to college in New York’s Hudson Valley. When the decision came down months later, it was 7–2 against us.

The implications were profoundly bad. CTS, an electroplating company, had dumped carcinogenic chemical solvents into the ground for decades, then shut down their factory in the 1980s. Meanwhile, toxins were seeping slowly from the abandoned building, infiltrating wells and streams. By the time people started getting sick, years had passed. A group of concerned citizens cobbled together a lawsuit in 2011 to seek damages for the hardship caused by the company’s negligence. CTS essentially claimed that we had waited too long. No, we argued: While your factory sat empty its pollutants were continuing to sicken us; we were under the surgeon’s knife and waiting for the next round of chemo and burying loved ones. The question before the Supreme Court came down to whether or not we had grounds to sue.

Industry heavy hitters threw their support behind CTS. After all, a decision in our favor would have had far reaching implications. Our small citizens’ lawsuit had morphed into a David-versus-Goliath battle. And Goliath won.

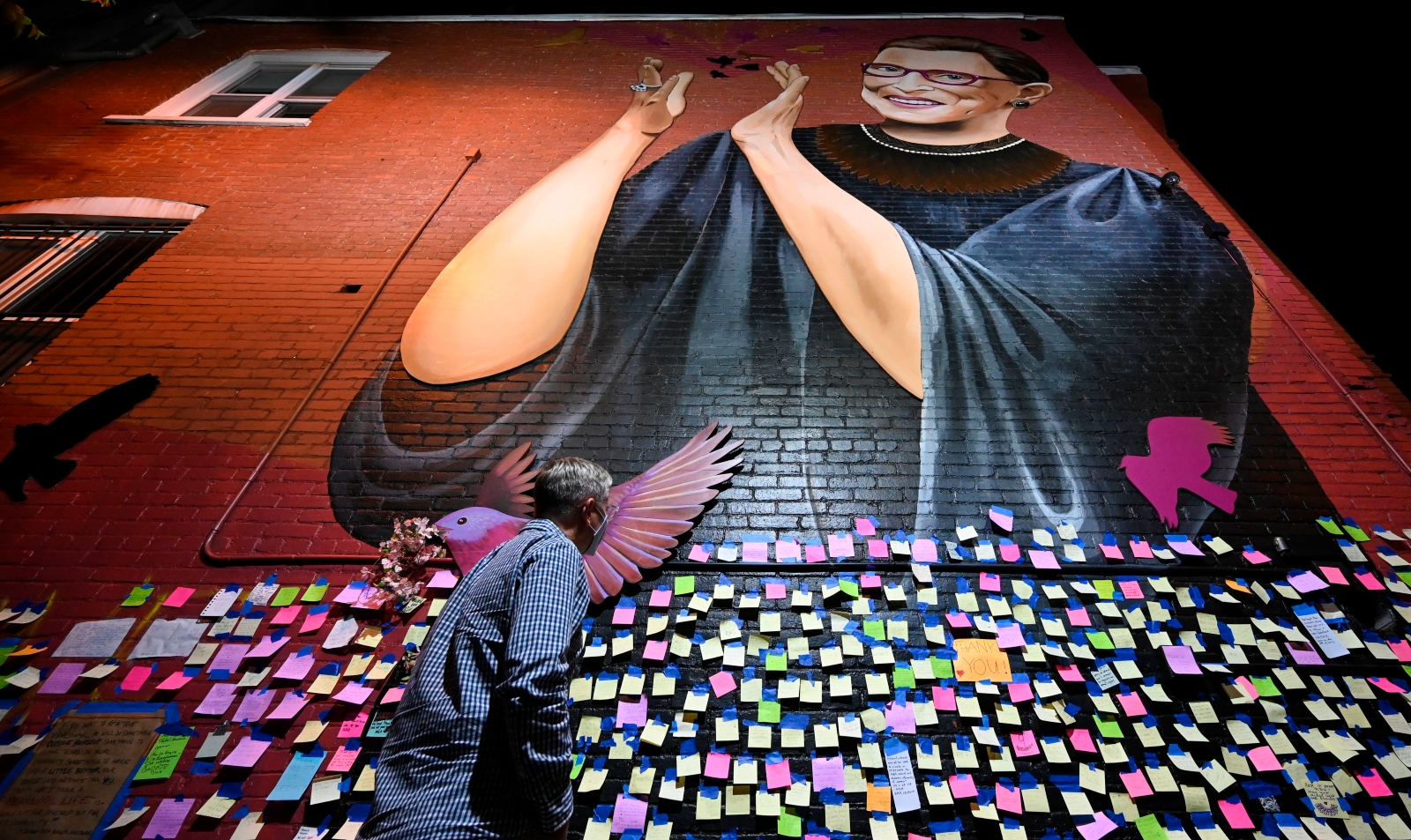

Amid the fury and despair that followed, I took hope wherever I could find it — most of all in Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s dissent. RBG wasted no time in excoriating the justices in the majority for the immeasurable suffering the decision condoned.

“The Court allows those responsible for environmental contamination … to escape liability for the devastating harm they cause,” Ginsberg wrote. Instead of “remediation of toxic contamination before it can kill, the Court’s decision gives contaminators an incentive to conceal the hazards they have created.”

RBG’s opinion, of course, wasn’t enough to sway the case. Yet in the midst of our defeat, a powerful voice had cast her lot with us. Justice had not been served, but at least its spirit had been uttered in the pages of her dissent.

In it lies a seed of hope. In its defiance is a reminder to never let injustice have the final say. No one, in the end, can take that dissent away — it belongs to all who would follow its light.

Already, recent court decisions have heeded RBG’s words in essence if not in name. In 2017, Teflon manufacturer DuPont was ordered to dole out $671 million to residents of West Virginia who were sickened by its contamination of local waterways. This past summer the chemical giant Bayer was forced to pay $1.2 billion for its subsidiary Monsanto’s longstanding pollution of the nation’s bays and rivers, alongside $10 billion for claims that Monsanto’s Roundup herbicide caused cancer — one of the largest civil settlements in U.S. history.

Just a few years ago, it seemed inconceivable that courts would tie cancers to the toxins that caused them. The tide may well be turning. And that’s the result of people on the ground doing the slow, painstaking work of organizing to fight the companies responsible and advocating for the government to do its job — it is, in a word, dissent.

As a teenager, several years out from my recovery from cancer, I spent my summers hand-painting signs to hang on the old factory gates: Clean water is a human right; We all live downstream; No more cancer; Cleanup now. I went door-to-door putting up flyers to get neighbors out to community meetings. My parents and I planned a roadside vigil. When the EPA came to town, locals packed the room. We put enough pressure on the agency that they eventually placed the site on their Superfund inventory, a list of the most contaminated sites in the nation.

I carry RBG’s dissent with me every time I return home. Whenever I drive by the chain-link fence that surrounds the derelict site, I know that the right to hold polluters accountable is a fundamental thread in the tapestry of environmental justice. When corporations treat the land as a dumping ground, then close up shop and flee, those who live here day-to-day are left picking up the pieces. Why should we not claim as recompense the profits that were predicated upon our suffering?

As the Supreme Court reconvenes with an empty seat and the country braces for the battle over who will fill it, Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s commitment to the rights of humans over corporations, evident in the dissents that live on, remind us what’s at stake. Honoring her legacy means carrying on the arduous, necessary, and life-affirming work of dissent.