This story is part of Fix’s Outdoors Issue, which explores how we build connections to nature, why those connections matter, and how equitable access to outside spaces is a vital climate solution.

“If at any point you need to bail, I’m right behind you,” said Luci.

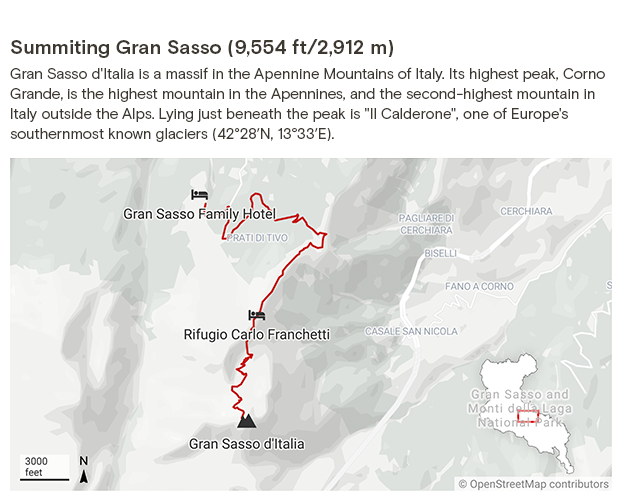

We were the caboose of a six-person hiking group, hoping to reach the 9,500-foot summit of Gran Sasso — one of the tallest peaks in Italy’s Apennine Mountains, two hours east of Rome — by sunrise. The moon was full. Stars filled the endless navy sky. My gaze drifted from my boots in the dewy grass up thousands of feet to the mountains’ dry, jagged peaks. I nervously shuffled one foot in front of the other — this was the farthest and steepest hike I had ever gone on. A familiar coat of fear settled at the back of my lungs.

I live with a rare, chronic illness called granulomatosis with polyangiitis: When flaring, my immune system becomes overactive and attacks my vascular system. My blood cells aren’t able to get the oxygen they need, which can lead to organ failure. I have lowered heart function, a transplanted kidney, limited hip mobility, and a medically suppressed immune system.

When I’m hiking, I sometimes worry about having a medical emergency, about how my disabled body will react, and how the people I’m with will respond. My heart condition makes me more susceptible to heat sickness and stroke, so I have to stay well-hydrated and rest frequently under whatever shade I can find along a trail. Another challenge can be carrying enough water, gear, and emergency supplies without schlepping too much weight for my heart and lungs to handle. I have to pace myself, because overusing my hip joint is painful, and I don’t want to get stuck with miles of trail left to go. I was reaching beyond my comfort zone that morning, and as I looked toward the peak it hit me that our Apennine adventure, if gone wrong, could have serious, long-term implications on my health.

The trip to Gran Sasso was a part of my growing desire to spend time in wild, wide-open spaces. My conscious relationship with the outdoors began when I was a kid canoeing the canals of the Chicago River system. At a city ecology camp, I studied the box turtles and great blue herons that coexist among aqueducts and dams created during the Industrial Revolution to keep waterborne diseases at bay. Growing up in a heavily developed area on Lake Michigan, I wanted to understand how nature was managed and protected outside of my own backyard. Given my medical history, it took me a while to feel safe outdoors, farther from medical care and resources, and not everyone was helpful in figuring out how to do so safely.

Ableism is the system of assigning value to a person based on perceived physical, mental, or cognitive abilities. Fifteen percent of the world’s population, and 26 percent of the U.S. population, live with disabilities, ranging from mobility differences, to depression and anxiety, to neurologic diseases, and these disproportionately impact Black and Indigenous communities. Access to the outdoors for people with disabilities is an issue in every community, and I have seen ableism play out many times. Once, several of my coworkers called a 5-mile hiking loop on the property “basically a walk” and thought it unnecessary to have a log book to ensure hikers made it back safely.

In my first year of college, I joined the school’s outdoor recreation club. I remember the worn, red tent the club set up inside the campus center during the fall activity fair and their enthusiastic welcome. I introduced myself to one of the group’s leaders and expressed my eagerness to try backpacking in spite of my pre-existing conditions. I was nervous, but excited. I couldn’t wait for the spring break backpacking trip. However, when it came time to sign up, the club’s leader pulled me aside and told me I couldn’t “ask for special treatment or access to trips” because of my medical issues. “You need to consider what’s best for a group when you sign yourself up for risky situations,” so I should sign up for trips at my own level. And then, almost as an afterthought, this person added, “And, hey, you can even lead them.”

I walked away and sat down next to a friend. At first I was confused: What had I done wrong? Having conversations about accommodations for my disabilities had become a normal part of how I navigated the world, and I always understood participation as my right. Now I was being told that was wrong. My face went hot with shame and wet with tears. I felt a hard pang in my heart and told my friend, “I’m not sure what just happened, but I know it’s wrong.” Later, I recognized that it was discrimination.

I did, however, take the club leader’s suggestion to organize ability-inclusive trips.

Throughout college, I led overnight campouts at the local state parks, road trips across the Southwest, and well-paced backpacking trips that circumnavigated Georgia’s Sea Islands. Prior to hitting the road, I would reach out to everyone and see what accommodations they needed. I would create accessible itineraries with built-in flexibility, should we need an extra day to rest or for anything else that might come up. During our pre-trip meetings, we made space to talk through questions, hesitancies, and most importantly, what we were excited for. Often, I’d be leading people on their first outdoor recreation trip, and it was always my goal to make sure they’d want to go on another.

Growing up as a disabled person, doctors and loved ones consistently told me to avoid risks, and with good reason. But I believe that having access to nature is a human right, whether it’s sitting in a tree-filled city park or trekking across a rural, open plain. The quiet moments of being present in nature help me slow down. The stillness is a comfort. In getting outdoors, everyone should be able to balance their own desires with risks, rather than be seen solely as a risk by others.

In getting outdoors, everyone should be able to balance their own desires with risks, rather than be seen solely as a risk by others.

In college I didn’t just encounter this attitude from the group’s leader. Some people don’t want to feel held back by others; they want to use a group excursion to set a personal record or reach a summit. That desire isn’t wrong, but the needs of everyone in the group must come first. I’ve seen people get abandoned because they’re at the back of a pack.

This kind of behavior may stem from ableism, but I believe it is rooted in a system of supremacy that values the lives of white, heterosexual, cis-gendered, able-bodied people above those who do not hold those identities. Inclusion in the outdoors isn’t difficult; it means communicating about desires and abilities, looking at maps together, and planning how the trip can be organized in a way so nobody is left behind.

On Gran Sasso, the rest of the group kept speeding far ahead of Luci and me, then waiting for us. I had met Luci a few weeks before, and we’d become fast friends. Luci is a listener, and I felt lucky that she had fallen to the back of the pack with me. When we all reconvened at the edge of the basin, about one-third of the way up before the loose-rock scramble to the summit, the sky had begun to warm with purple and we could clearly see how far we had yet to climb. We agreed that the rest of the group should keep going at their pace; if Luci and I needed to turn back, we would.

As we ascended the tree line, my confidence was shaky and it showed. Every few steps, I stopped to look behind at the shrinking trailhead. Luci took notice, and we halted in our tracks. “Pausing!” she shouted from behind. As someone who also hadn’t summited a mountain before, she set her pace low and slow, encouraging me to lead us toward the peak. We stopped when we needed bigger breaths, handfuls of snacks, or a shared moment to step back and take in the expanse of the mountain range.

Luci and I pushed our edges and reached the summit, reuniting with our team. If we had kept pace with others, I would have felt overwhelmed, out of place, and unsafe. I was grateful she was there. As we leaned against Gran Sasso’s peak among the clouds, sipping well-jostled Italian beers, it felt like true teamwork.

It has been several years since our Apennine adventure, and since then, I’ve more or less figured out what I need to be comfortable and confident while exploring the outdoors. I always pack a fully stocked med kit, try to limit hiking to 10 miles or less per day, and carry medical info that the group I’m with can access in case anything were to happen. In establishing both my needs and emergency plans, I have generally garnered the support essential for my excursions with others.

For me, being a disabled person doesn’t mean I have to reach the summit or be in front of the group to know I’m tough — the metal thread binding my ribcage together following open-heart surgery does that for me. What I’ve found over time is that without the support of fellow adventurers, I don’t get outdoors as often or in the ways that I need to. Without knowing that someone will hang back with me on the trail if I need to slow our pace, or reliably check in about how I’m feeling, I feel unsupported and overwhelmed by fear. But with the power of true teamwork, I have been able to confidently hike, bike, and climb, building relationships with incredible parts of our natural world.

To face climate change, we need every person ready to protect the places they hold dear. We know that climate change will more significantly affect people with disabilities and that environmental pollution is disabling people who live in proximity to it. There’s also evidence that spending time outdoors brings significant health benefits for everyone, so outdoor recreation must be safe and accessible in every community.

Last December, I went to Hyalite Canyon in Bozeman, Montana, and filmed an ice-climbing clinic with athletes from Inclusive Outdoors Project and Paradox Sports. With their care and support, about a dozen people with limb and mobility differences — including people with one arm or leg and those using a walker — climbed a vertical ice sheet in 15-degree weather. There are more and more groups doing this important work.

As Pattie Gonia, professional drag queen and cofounder of Outdoorist Oath points out, the outdoors don’t discriminate — it’s the people who create such a culture. The oath is a pledge to protect not only the environments that we adventure in, but everyone’s access to them.

These days, I hike rugged terrain from deep in the North Cascades of Washington to the backcountry of Montana and bring nature to people through video, photography, and journalism. The eternal search to feel small under a big sky has taken me from my own backyard to Big Sky Country and across the world. I don’t plan on stopping anytime soon; I’ll just make it there at my own pace.

Aj Williams is a freelance multimedia journalist in Missoula and a graduate student at the University of Montana studying environmental science and natural resource journalism. Williams is currently at work on a documentary about disability access in outdoor recreation.

This article is published in partnership with The Xylom, a nonprofit student-led newsroom exploring the communities influencing and shaped by science.

The views expressed here reflect those of the author.

Fix is committed to publishing a diversity of voices, and we want to hear from you. Got a bold idea, fresh perspective, or insightful news analysis? Send a draft, along with a note about who you are, to opinions@grist.org.