Alexandra McFadden has a plan for revitalizing the Philadelphia neighborhood where she grew up. Too bad it’s totally illegal.

McFadden was raised in the East Parkside section of the city in the 1980s. Back then it was a tight-knit community where people took pride in their colorful Victorian row houses and tree-lined sidewalks. The neighborhood, which dates to the 1870s and sits alongside Fairmount Park and the Schuylkill River, always struck her as a peaceful pocket in a bustling city. “There were entire blocks of well-maintained houses, with little front yards and elderly ladies who peered out at the kids playing,” she says. “They’d shout, ‘Don’t toss that ball into my yard!’”

Things are different these days, though. One in three residents live in poverty, nearly half of the original housing stock sits vacant, and empty lots attract litter and commercial dumping. “There are junk cars and barrels full of mysterious stuff,” McFadden says. “It leads to runoff, and we have no idea what chemicals are going into the soil.”

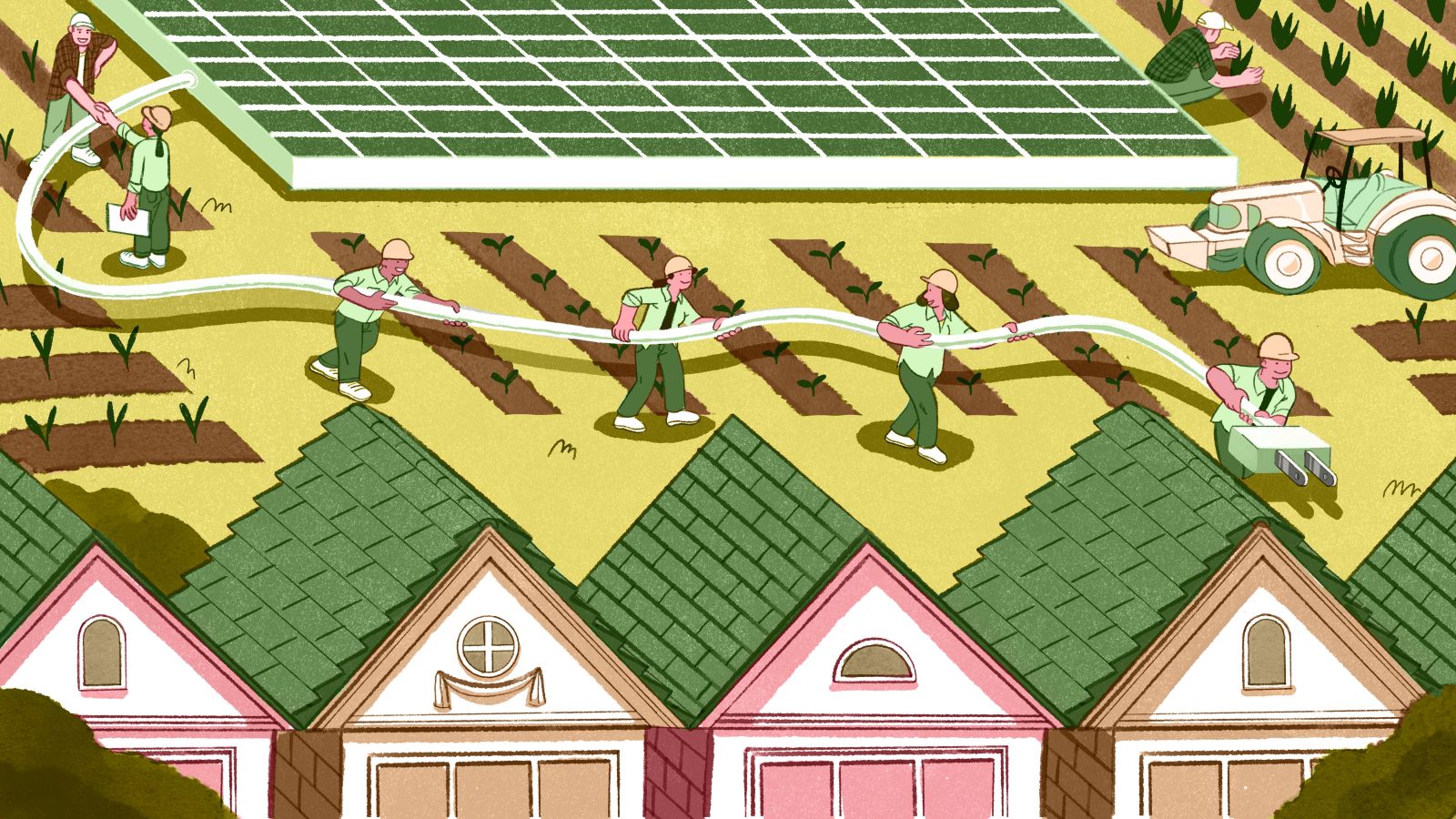

McFadden returned to East Parkside a few years ago and is now board president for Centennial Parkside Community Development Corporation (CPCDC), a nonprofit that supports local businesses, maintains affordable housing, and keeps the neighborhood green. It hopes to turn blight into opportunity by establishing solar-farm cooperatives that would provide residents with affordable clean energy and bring new investments to the community.

The idea is to remediate underutilized land and use it to erect solar arrays. Nearby institutions like the Philadelphia Zoo and the University of Pennsylvania would purchase energy from the project, and CPCDC would use the resulting revenue to finance the construction of more rooftop solar arrays, along with programs like job training and food pantries. Residents can also subscribe, and their ownership stakes would earn them credits from PECO, the local utility, for providing renewable energy to the grid, reducing their overall energy bills.

“The idea of having an organization fund itself without relying on grants — which are often fiercely competitive — is super interesting,” McFadden says. “I’m sold on the idea of using a sustainable resource, especially in a community that frequently lacks environmental justice power.”

The plan is undone by one thing: Pennsylvania, like 29 other states, bars ownership of photovoltaic arrays by more than one entity. Past efforts to change that outdated law have failed in the face of intense opposition by energy companies, but a bipartisan coalition of solar advocates, farmers, and lawmakers hopes to push a new bill through the statehouse.

‘People don’t understand why we can’t do this’

The community solar model started 14 years ago in Sacramento, California, when the city utility launched SolarShares. For a modest monthly fee, residents who could not afford photovoltaic cells, or had nowhere to install them, could tap a public array. Even with the subscription cost, folks saw their energy bills decline because they earned credits for sending unused power to the grid for others to use, easing the utility’s need to generate electricity.

Co-ops provide a relatively easy way of democratizing expensive technology. The average cost of outfitting a home in Pennsylvania, for example, can range from $12,708 to $17,192. But when Sacramento launched its program, most states barred the creation of shared solar arrays. That began to change in 2010 when Colorado passed the first law allowing individuals, businesses, and nonprofits to build, manage, and benefit from arrays. Twenty states, and Washington, D.C., have since followed suit.

Community solar projects are popping up across the country. The nonprofit BlueHub Capital transformed a brownfield in Gardner, Massachusetts, into a solar field, for example. It provides power to an affordable housing development and an organization that supports people with disabilities while creating revenue for the city, which leases the land. Jeff Cramer, executive director of the Coalition for Community Solar Access, says cooperative arrays like that power approximately 380,000 homes for a year. As the Biden administration pushes clean energy, he anticipates that figure increasing exponentially by the end of the century — assuming states that ban co-ops change their ways.

The recent blackouts in Texas only make cooperative energy more attractive, according to McFadden. Shared solar would give resident owners a say in operations, ensuring that reliability is prioritized. That’s especially important in majority-Black communities, like East Parkside, which have historically faced energy insecurity. “I think we’re an afterthought in many ways,” McFadden says. “It would be great if we were able to take more control of our energy destiny — or just our destiny, period.”

People have been trying to change the law in Pennsylvania since 2018, when Democratic state Representative Donna Bullock introduced legislation that would eliminate the state’s restriction. Bullock, whose district includes East Parkside, believes the technology will create jobs, foster energy sovereignty, and allow renters and those who cannot otherwise afford it to benefit from the economy of scale that a cooperative offers.

Her bill didn’t get far, despite bipartisan sponsorship and widespread support. Republican state lawmakers Mario Scavello and Aaron Kaufer tried again with similar bills in 2019. They represent largely rural districts, where community solar is popular among farmers looking to offset their high electricity costs and lease their land to project developers. Their efforts met the same fate as Bullock’s, but Scavello introduced yet another proposal last month. He argues going solar will create jobs and provide affordable energy for folks at a time when, due to the pandemic, many people are still struggling to pay bills.

He has the numbers to prove it. A 2020 study by researchers at Pennsylvania State University identified 235 community solar facilities awaiting the legal go-ahead. Combined, they would power approximately 120,000 homes, create 12,000 jobs, and save consumers $30 million per year in electricity costs. According to a recent survey, 77 percent of Keystone State voters favor changing the law.

The diverse coalition of folks aligned behind the measure underscores the appeal of solar power, says Henry McKay, Pennsylvania program director for the advocacy organization Solar United Neighbors. He says people across the state are excited about community solar’s potential. “It’s an intuitive, obvious idea,” he says. “People don’t understand why we can’t do this.”

Bridging ideological divides

Despite its bipartisan support, the bill failed to overcome a lack of inertia within the state legislature. Opposition to solar is everywhere — some folks consider arrays unsightly and worry about them driving down property values, according to NPR, while others worry about the impact on wildlife and storm drainage.

According to Scavello, for-profit utility companies remain a key hurdle to adopting community solar. He says he’s found that companies worry about cooperative arrays undermining profits. “When you introduce something, no matter what the legislation is, you’ll find people that you didn’t expect to come out against it,” he says. “And the utilities have a good lobbying group.”

Other states have faced similar opposition. As New Mexico’s legislature debated its own recently passed bill, Senate Republicans and utility companies worried that the law could mean increased rates for residents who don’t opt into community solar projects. A 2020 study by an Ohio University policy analyst found that, in eight states where legislation has been introduced, utilities opposed community solar on the basis that implementing it could be “a logistical nightmare.” The study also found that many lawmakers are uninformed about the nuances of the model, making them susceptible to lobbyists’ arguments against it.

Scavello says that he added provisions to his bill to ease utilities’ concerns and hopes those adjustments, along with the popularity of community solar, will finally get the bill passed. “I think utilities realize that continuing to fight this will be bad press for them,” he says.

Pennsylvania is a famously divided state, balancing the interests of a Democratic governor, a Republican-controlled legislature, and a population split, often along geographic lines, among liberal and conservative voters. Scavello says his campaign for community solar has led him to collaborate with politicians, activists, and interest groups he never would have expected to work with. “I’m starting to see that there are other things that we could work together on,” he says. “Solar opened up the door.”

McFadden is happy to see those doors open, but she’s more interested in seeing her childhood neighborhood thrive. Centennial Parkside Community Development Corporation recently bought a vacant building, which it has used as a pop-up food pantry throughout the pandemic. The goal is to convert the first floor to office spaces and the upper floors into affordable housing.

The plans also call for a photovoltaic array on the roof, to educate residents about the technology and the potential it holds. One day, McFadden would like to see panels filling the vacant lots throughout the neighborhood, powering new businesses and community centers while keeping her neighbors’ lights on and bills low. It’s just a dream for now — unless, this year, lawmakers decide to turn it into reality.