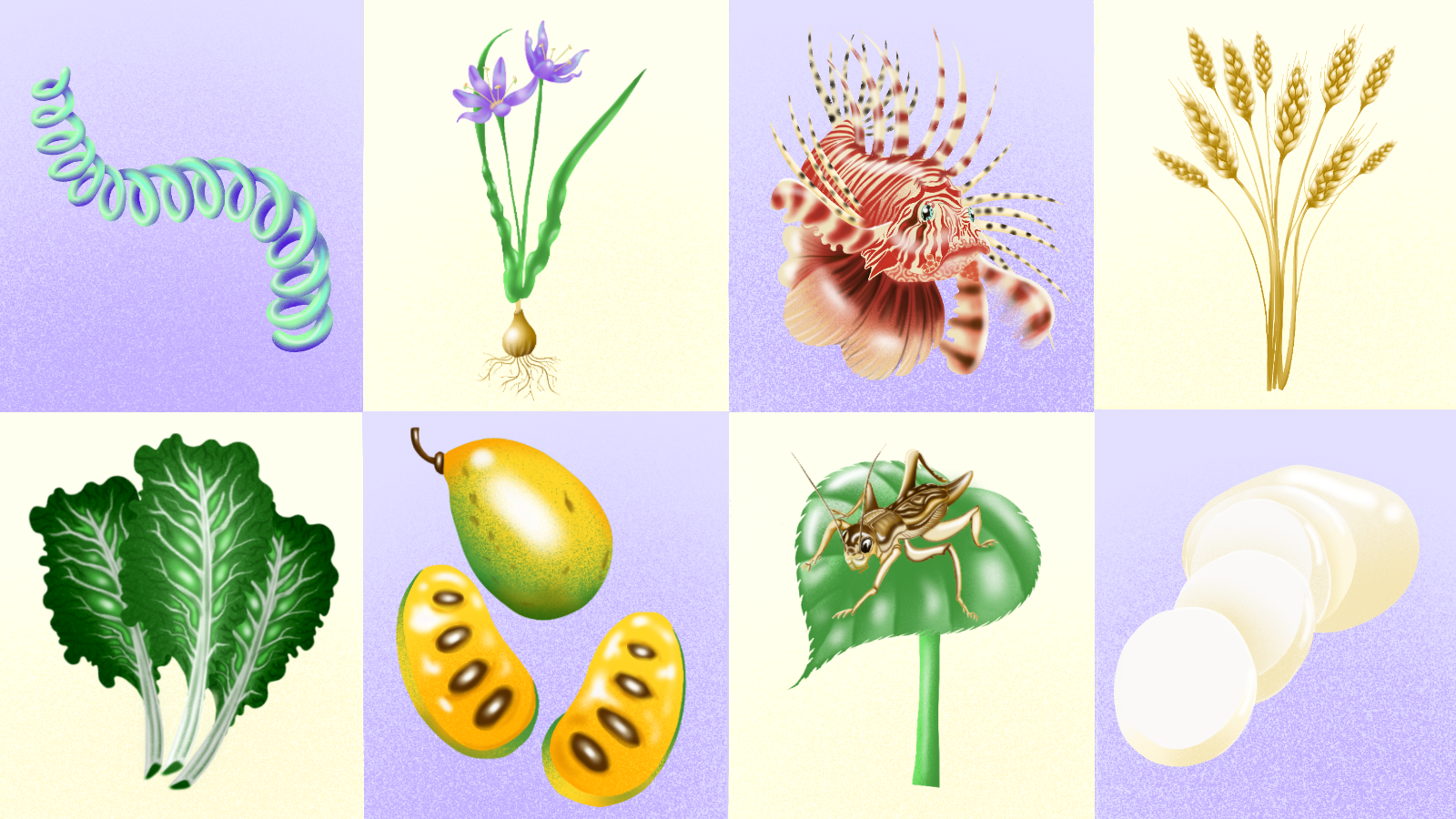

As our climate changes, so will our diets. Fix’s Future of Food Issue explores that reality through the lens of foods that show what sustainable, equitable, and resilient eating could look like. Try them yourself with the recipes in our Climate Future Cookbook.

Meditation takes many forms. For some, it’s sitting cross legged with incense burning. For others, it’s kneeling in prayer. And for a few, it’s hauling hay across a half-acre while the still-rising sun strokes your shoulders. This was the first of many lessons I learned on my first day volunteering at Yes Farm.

This acre-and-a-half urban farm nestled in central Seattle isn’t what most imagine when they picture a farm. Instead of the crow of a cock, the moo of a cow, and the baa of a sheep, the air of Yes Farm is filled with the din of cars cruising by on I-5, the occasional chop of a helicopter landing at Harborview Medical Center, and the discordant drumbeat of hammers falling at a construction site next door. Even among all the sounds that, much like a middle school marching band, never quite come together, the work soothes. As soon as I dig my hands into Yes Farm’s soil, all the noise fades away.

The farm is tended by the Black Farmers Collective, which was founded in 2016 to acquire land adjacent to a Seattle Housing Authority redevelopment on Yesler Terrace to create the farm. After two years of navigating a maze of paperwork, the collective began tending the soil of Yes Farm in 2018. Over the past four years, it’s grown collards, corn, squash, spinach, arugula, and other vegetables. It’s set aside plots for medicinal herbs traditional to the Asian and African American communities who have historically called this neighborhood home. It even has raised-bed gardens specifically for BIPOC community members without space to grow food at home.

All of this contributes to the collective’s mission to build a Black-led food system. It also affords people the chance to deepen their roots in the community, understand where their food comes from while growing their own, and reconnect with the land.

I’d wanted to get involved at Yes Farm since I first heard about their work in 2020, but I teetered on the edge for almost two years. I wasn’t sure I had the time, I didn’t think I would be any help without farming experience, and I didn’t know anyone at the farm. Then, in July, I heard the farm was hosting a BIPOC summer cookout and figured it was time to see what it was all about.

As I walked down the steep dirt slope off Yesler Way, through the front gate, past vendors on one side of the path and a group of Black and brown bodies folding through a yoga flow on the other, I felt at home. I grabbed a plate of jollof rice, chicken stew, and a mixed green salad — all prepared by a local West African chef, with vegetables sourced from the farm — and snagged a seat in the sun. As I ate, I chatted with volunteers over the speakers bumping bass-heavy beats. They shared how much the farm meant to them as a space to grow as individuals, plant seeds of friendship, and give back to the community. The longer I was there, the more I breathed the fresh evening air filled with laughter and Black joy, the more I knew I had to blend with the community that has blossomed there.

My first day volunteering, I hauled hay and pulled weeds. Not exactly glamorous, but nonetheless fruitful and eye-opening. Beyond the meditative nature of manual labor and the serotonin-releasing benefits of digging in dirt, I also came to understand the thanks we owe for the food we eat. This lesson would crop up again and again, but Ceci Huívar was the first to bring it to my attention.

Before moving to Seattle and volunteering on Yes Farm, Huívar spent time supporting an animal farm in Nevada through the Worldwide Organization of Organic Farms, where she learned how to butcher an animal while paying respect to its life. She described how her experiences taught her how grateful we should be for every bite we eat and how, be it fruit or meat or vegetable, we should thank the living beings who nourish us.

Yet, as we wind through supermarket aisles, we don’t think about all that goes into stocking the shelves. (I know I don’t. Or at least, I didn’t before the farm.) I never thought about all it takes for a seed to sprout and leaf, to bud and blossom, to flower and fruit. I never thought about the hands that pinch and pluck a plant just so, to harvest it. I never thought about the trucks, planes, and ships that carry food from farms, sometimes continents away, to my neighborhood market. I never thought about the grocers who stocked the shelves, even as I reached around them to grab an onion grown god knows where. I certainly didn’t thank them, or anyone else in this long chain stretching from planting to pantry.

Shabazz Abdulkadir, a young Black woman working to make the farm ADA accessible, told me about the first time she brought her cousin to volunteer. When they walked off the farm, Abdulkadir’s cousin said to her, “I’m never taking a strawberry for granted again.”

Working on the farm surprised Abdulkadir in similar ways. As we spoke, she recalled her first time watching the crops through a full season. She came to understand how certain things can’t be rushed. “You think three months is such a long time,” she says, “and then you watch a plant grow and realize it’s not that long at all.”

Seeing their leaves slowly unfurl, and their stalks inch toward the sky week after week, taught her patience. Watching how they pause to gather energy before flowering and before fruiting offered a lesson about rest.

These are experiences the collective wants to share with the whole community. To do that, the farm holds seedling classes, mushroom workshops, and other events to teach community members about farming and food justice, and to provide people a chance to internalize what plant-care teaches us about self-care.

“Tending the plants has helped me tend myself,” says farm manager Hannah Wilson, “and because I have more food, I can care for others more.” They’ve seen this same effect ripple out into the community.

The staff and dozens of volunteers have grown more food this year than ever before, and they’re refining their distribution system. So far, they’ve gotten their produce in community members’ hands through farmers markets, mutual aid systems, food bank donations, farm-hosted cookouts, and people coming through to harvest on their own. Over the next year, the farm plans to tighten connections with Black-led food banks and other organizers to get their harvests distributed around food deserts.

[Read more: How fruit trees can be a solution for both heat and food justice in cities.]

Because the Black Farmers Collective helps people get healthy and affordable (if not free) food, it can be part of helping struggling BIPOC individuals out of survival mode. Then, those folks can give back to the community in their own ways. This creates an atmosphere of reciprocity like that seen in the symbiotic Three Sisters, a crop mix central to Indigenous agriculture and grown at Yes Farm.

Corn, beans, and squash have been grown together across Turtle Island for millennia because of the way they support each other. Their leaves, their stalks, and their roots each grow at different speeds in different ways to different heights and different depths. All these differences keep the whole healthy and strong. The Three Sisters “reflect how interdependent we all are,” Wilson says. “Each of us has a role, but we all still need each other.”

This regenerative, healing approach to agriculture is particularly essential to Yes Farm because this work can be, as Wilson says, “painful for Black folks.”

With our ancestors snatched from their shores, stowed as cargo, and shipped across the Atlantic to spend centuries never reaping what they sowed, many Black Americans put farming behind them as soon as they could and swore they’d never look back, especially in the face of post-Emancipation persecution. In her essay “Black Gold” published in All We Can Save, Leah Penniman (a 2019 Grist 50 honoree) put it best: “For many of our ancestors, freedom from terror and separation from the soil were synonymous.”

However, as our collective disconnection from the land grows, as rates of mental illness rise, and as knowledge of farming’s healing effects expands, many young Black folks, myself among them, yearn to reach back into the soil to grasp the roots we left behind. This is what makes urban spaces like Yes Farm so important.

Across the country, community-centered urban farms — Black-led or not — offer teachings like those I received over a few short weeks working at Yes Farm. The farm taught me much about the future of food and living in a time of tremendous change. We must respect the life that feeds us. We must have patience for the time it takes for change to manifest. We must listen to the cycles of rest and growth and abundance we move through. And we must play our role wherever we’re planted. But above all, we must build connections with those around us by loving, respecting, and uplifting each other regardless of our apparent differences.

As we heal our relationships to the land, we can deepen our relationships with each other, we can learn to respect each other more than we otherwise would. As we embrace the lessons of the land, we can use our deepened connections to advance the lasting changes that will remake our world into a garden of grace and goodness.

Read more about the future of food:

- The Indigenous tribe reviving native camas and the prairies that sustain it

- Pets eat a lot of meat. Feeding them insects could lower their carbon pawprint.

- Why algae could be a ‘magic crop’ for a drought-stricken world