Joy can strengthen our resolve, help us unlock creativity, and bolster our resilience. In Fix’s Joy Issue, we explore the importance and power of finding joy in the face of grief, anger, and a changing climate.

I recently attended a comedy show at a small club in Brooklyn. The final performer asked the crowd to toss out a topic for his closing joke. I enthusiastically shouted, “Climate change!” — which he promptly shot down: “No one wants to hear jokes about climate change, it isn’t funny.”

He had a point. The climate crisis, its deadly impacts, and the chronic injustices that underpin it aren’t inherently chortle-worthy. But for some, that’s exactly why comedy can be a powerful tool in how we deal with it.

“I think you have to have a little bit of a grounding in absurdity to do this work,” says Bora Chang, an adjunct lecturer in the Earth and Environmental Sciences Department at the Columbia Climate School. “Nothing about this is funny. And yet it is so absurd that you kind of have to laugh.”

Humor not only makes us feel good, it can help us process, relate to, and retain information. Studies have shown that climate-related comedy can help people feel more optimistic and more committed to taking action. There’s even a study out there showing that exposure to climate change memes increases people’s intention to engage with online climate action.

Advocates are beginning to see the opportunity in this. Meanwhile, as climate awareness has grown, more comedy creators have started exploring the issue in their work, from small stages to hits like Don’t Look Up (Netflix’s second most-watched film debut) and Bo Burnham’s wildly popular special, Inside.

So there, Brooklyn guy.

The science of humor

Although humor is different in every culture and for every person, humans naturally tend to connect with others through shared mirth.

“In the humor literature, there’s been a long, long debate about humor appreciation — what makes something funny,” says Sara Yeo, a science communication researcher at the University of Utah. She’s a believer in the theory of “benign violation,” which essentially means humor is born of a perceived threat being rendered safe within the context of a joke, a bit, or a playful act like tickling.

“One of the things that I’ve been thinking about is the threat of scientific information to people’s existing beliefs or worldviews,” Yeo says, “and whether one can make that seem more benign in some ways through the use of humor.” Yeo is considering a study to explore whether humor can make people receptive to information they disagree with. Her research already has shown that joking can make scientists and science communicators more likable and seem more credible. This is something Chang teaches in her strategic climate communications course. The best way to persuade an audience to understand your position and act on it, she says, is to be likable. “No one wants to listen to a bummer-sauce person.”

Yeo is considering a study to explore whether humor can make people receptive to information they disagree with. Her research already has shown that joking can make scientists and science communicators more likable and seem more credible.

Environmentalists have long received criticism for being preachy or taking themselves too seriously, in some cases becoming the butt of the joke. (Al Gore being a perfect example.) And when a joke has a butt, it can actually act as a social wedge, Yeo says, further consolidating “in-groups” and “out-groups.” For instance, climate communication often employs satire, but Yeo has found “that type of humor doesn’t appear, at least from my research, to be particularly effective in reaching groups that are outside of the sphere.” It may feel good to people in the know, but she believes more benign forms of humor — things like wordplay or anthropomorphism that don’t target anyone — have the potential to sway more people who are not yet in the climate camp.

She and Chang also emphasize that the identity of the messenger is important in determining who will listen and how they’ll react. “You definitely want people to reflect you and your values,” Chang says. And, given that climate action requires a critical mass, communicators must represent all communities. “We need more messengers who are good at it, and can point to the damage that people in power are doing in a way that is engaging and inspiring and activating,” she says.

Laugh first, learn second

For science comedian Kasha Patel, climate change is one of the most challenging topics she’s tackled. “It’s really hard to fight against what people’s preconceived notions are,” she says. “Even just the words ‘climate change’ can turn people off.” She runs science-themed comedy shows in the D.C. area, and has struggled to find good headliners who have science- or climate-related material, let alone who identify as science comedians.

Still, over the past eight years, she has seen more comedians — some famous, some open mic-ers — taking on climate themes. They might not be promoted as climate comedians, but they’ll do a bit on veganism, or electric cars, or how damn hot it is. “Our world is changing, and comedians comment on that,” she says.

Patel has been doing stand-up for nearly a decade, while developing a career as a science writer and video producer that included several years at NASA’s Earth Observatory. It seemed natural to joke about what she knows. Her sets cover everything from science to bad dates to her experience as an Indian American from West Virginia. She wants people to leave her shows with a new perspective, but science education is not her primary goal. “I want my stand-up set to be funny first and then educational. Sometimes people reverse that — they want it to be educational with a little bit of humor,” she says. “Because I want to be labeled as a stand-up comedian, I always want to make people laugh first.”

And there may be great value to that. Patel recently led a study with Yeo and other researchers that examined how funny and effective audiences would find people — the same people, making the same jokes — when they were identified as either scientists or comedians. It’s still under peer review, but the results showed that when listeners thought the jokes were knee-slappers, they considered both the scientists and the comedians effective communicators. When they weren’t as amused, they judged the scientists more harshly and considered them less effective than the comedians.

[Read more: What research tells us about making space for joy in a time of climate crisis]

“People have the idea that scientists are serious people,” Patel says. “So if you make a joke that’s kind of half funny, they’re probably not going to give you the benefit of the doubt.” On the other hand, when she tells people she’s a comedian, she finds they’ll laugh at almost anything she says.

That gives comedians a unique opportunity. With people primed to find them funny, they can, as Patel puts it, “sneak” science or other discourse into their sets. “I think comedians probably have the most neutral position for disseminating information,” she says, “because people see comedians as communicators of information, just funnier.”

It’s a description that fits Rollie Williams, a comedian, YouTube personality, and a 2022 Grist 50 honoree. Williams started experimenting with climate comedy when he played Al Gore in his live show, An Inconvenient Talk Show. It started with him poking fun at the guy, but evolved into a showcase of interviews with climate scientists and journalists, including big names like David Wallace-Wells and Ayana Elizabeth Johnson. “Hilariously, climate scientists will go just about anywhere for no money,” Williams quips. “Climate scientists desperately just wanna go talk and inform people.”

As Williams learned more about climate, informing people became part of his mission as well. He went back to school and got a graduate degree in climate science and policy. Today, he fuses comedy and education in his Youtube show, Climate Town, which as of this writing has 367,000 subscribers and counting. Some of his videos have racked up over a million views.

In one bit about plastic recycling, Williams jokes, “We gotta stop treating ‘recycle’ like it’s the Beyoncé in the Destiny’s Child of reduce, reuse, recycle.” Beyoncé, Williams says, is both reuse and reduce, the more effective tools for combating the plastic scourge. And recycle is “the other two.” (Sorry, Kelly and Michelle.)

Although Williams hesitates to call himself an advocate, his videos mention actions viewers can take. In the description of the plastics episode, for instance, he lists links to legislation and organizations. He doesn’t necessarily think that’s what people came for, but feels it is the only satisfying conclusion to the material he presents. His primary goal is to share accurate climate information in an entertaining way, and let people take the next steps.

That’s why he focuses on easily relatable topics, like plastics, fast fashion, and gas prices. He wants to entertain and intrigue people who may not know anything about climate change.

“It’s just a topic that’s been slept on for a long time,” he says of climate in the comedy world. “And it’s probably because the barrier of entry is high, because it takes a lot of base knowledge to accurately and interestingly convey any part of the climate crisis.”

Healing the world with comedy

Waxing comedic about so serious a topic requires care. But humor may be an under-tapped resource for inspiring and bringing people into the climate movement because, as Patel notes, it is the ultimate unifier.

“Someone could make a joke [and] that same joke could make Obama laugh and make a kid in high school laugh. Comedy can just transcend different educational levels, different backgrounds,” she says. “So why can’t we use that for something like science?”

Some organizations and individuals are trying. Science-comedy writer Sarah Rose Siskind cofounded Hello SciCom to help scientists, engineers, and tech professionals tell their stories in accessible, engaging ways through humor. “Is it boring? We can make it not boring,” Siskind says of the company’s services. She and her team work on everything from public talks to investor pitches to online video courses — and, she jokes, “a Nobel prize acceptance speech one day, hopefully.”

“Comedy can transcend different educational levels and backgrounds. So why can’t we use that for something like science?”

— Science comedian Kasha Patel

Siskind emphasizes the importance of rewarding progress, rather than ceaselessly focusing on how much remains to be done. Environmentalists’ success mitigating the hole in the ozone layer is an example that she thinks hasn’t gotten enough play. “That was like the existential issue of my childhood, and we fixed it,” Siskind says. “And what I’m trying to say is, we deserve a pizza party. We should have a party under where the hole was.”

Siskind sees it as a way of drawing more people into the fight. After all, everyone wants to play for a winning team. She also believes that focusing on human heroism and ingenuity is crucial to giving people hope, and could be the most effective way of recruiting newcomers.

“Humans are great. Like, I know we’re terrible and there’s genocide and body odor and everything, but humans are amazing,” Siskind says. “I think we have to, frankly, take joy in what it means to be human.”

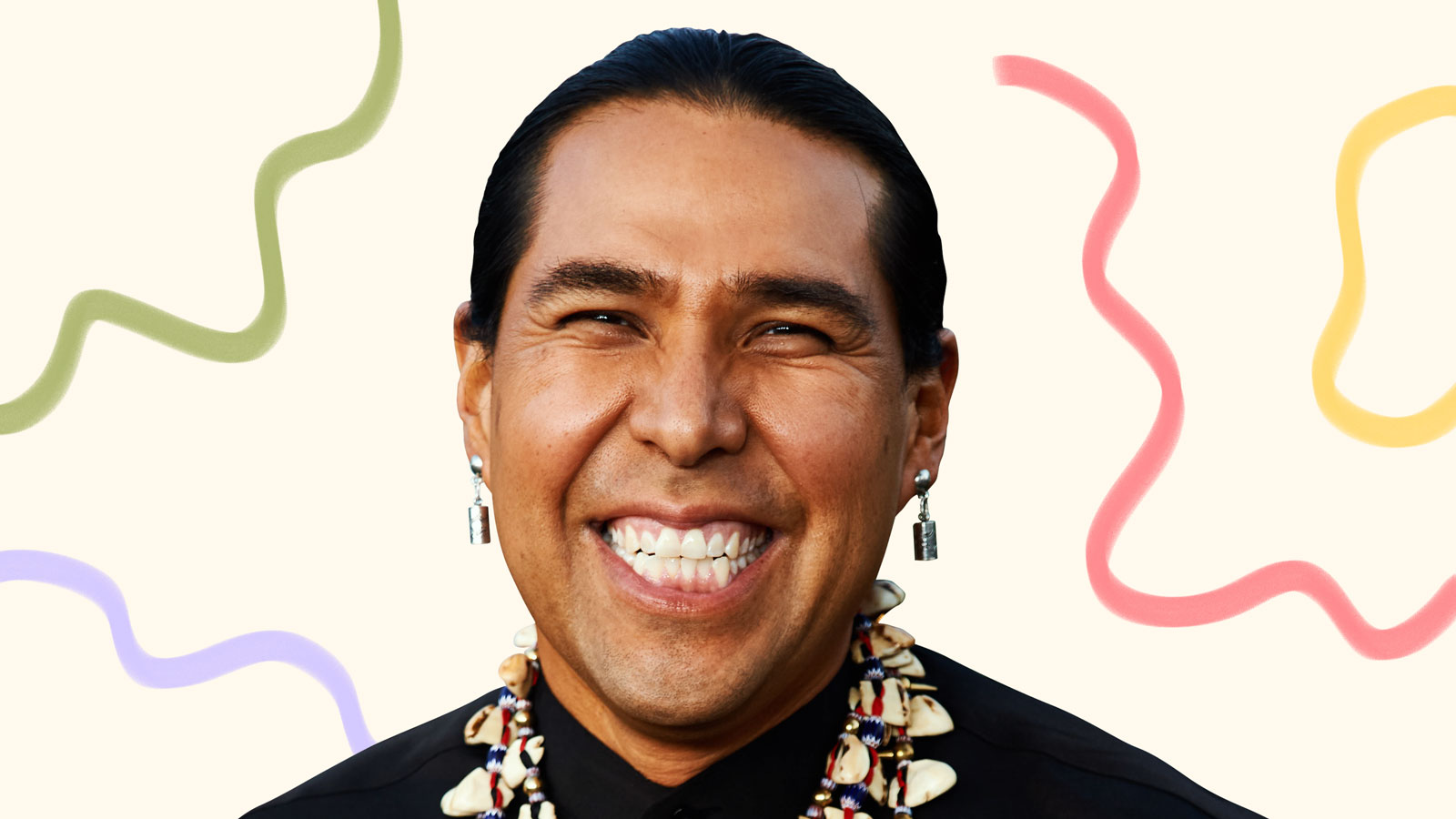

Embracing the messiness of humanity is a strategy that comedian Esteban Gast has used to tease humor out of the massive, complex topic of climate change. An entertainer with a background in education, Gast had dabbled in climate-related material — including a series of commercials for Hyundai in which he took a road trip in an EV. From there, he began working with the climate organization Generation 180, which combines political advocacy with cultural strategy to empower everyday people to make clean energy decisions. Eventually, Gast became the org’s comedian in residence.

In this unique role, Gast focuses on humor grounded in hope and actionable solutions, something he calls essential to using comedy as a motivator. “If we’re like, ‘Just have anyone talk about climate, and pour some humor on it’ — [that] is totally misguided,” he says. That’s how we end up with an overdose of “woe is me, we’re all going to die.” And if “we’re all going to die” is the only punchline people hear about the climate crisis, they’ll believe it. “If you tell someone it’s hopeless, they’re not going to act,” Gast says.

Making hopeful, motivational climate humor is a delicate balance. Just as audiences view most scientists as serious, they often see advocates as starry-eyed or earnest. But, to anyone who asks if climate optimism can be funny, Gast says yes — in the hands of a skilled comedian. “You can really make jokes about anything if you are thoughtful and creative,” he says.

That’s the idea behind the Climate Comedy Cohort that Gast recently helped launch at Generation 180 with the Center for Media and Social Impact. The cohort includes nine comedians, all of whom are at least climate-curious. Over the course of six months, they’ll learn about different aspects of the crisis and associated solutions from scientists, politicians, and activists. They’ll create writers’ rooms and ultimately engage in a friendly pitch competition for a chance to win $20,000 to finance a future project.

“We’re really investing in these comedians to organically make comedy in a way that makes sense for them,” says Gast. The goal is for the comedians to learn about climate issues in a way that will become part of their life experiences and work itself into their careers.

“Stand-up comedians have this unique life where they are traveling, telling jokes,” Gast says. “And in comedy, you can say really meaningful things and people listen.” He has been all over the country, doing shows in barns, Kiwanis clubs, and casinos. People who might not check out a documentary or a lecture about climate change probably will go see a comedy show.

“What? You tell me there’s a group of people that everyone across the ideological political spectrum is going to watch, and they’re selling out in Lincoln, Nebraska? Al Gore can’t go to Lincoln, Nebraska,” Gast jokes. “To introduce a little bit around climate change is, like, unbelievable. It’s a remarkable opportunity.”

Explore more from Fix’s Joy Issue:

- How climate organizers are making joy part of their toolkit

- Happy Climate is on a mission to show what we gain from climate action

- What the joy of dolphins can teach us about climate solutions