The vision

“How can queer ecology be employed in climate solutions? I think a lot about the intersection of queerness and climate-related conversations, and I want to know what else is going on in this field!”

— a question from Looking Forward reader Jess Savage

The spotlight

We received the above question from reader Jess Savage, a queer writer and ecologist, asking about the intersection between climate solutions and a school of thought known as queer ecology. In this newsletter, marking the last day of Pride Month, Fix Climate Solutions Fellow Marigo Farr breaks down the philosophy behind queer ecology and how it relates to climate.

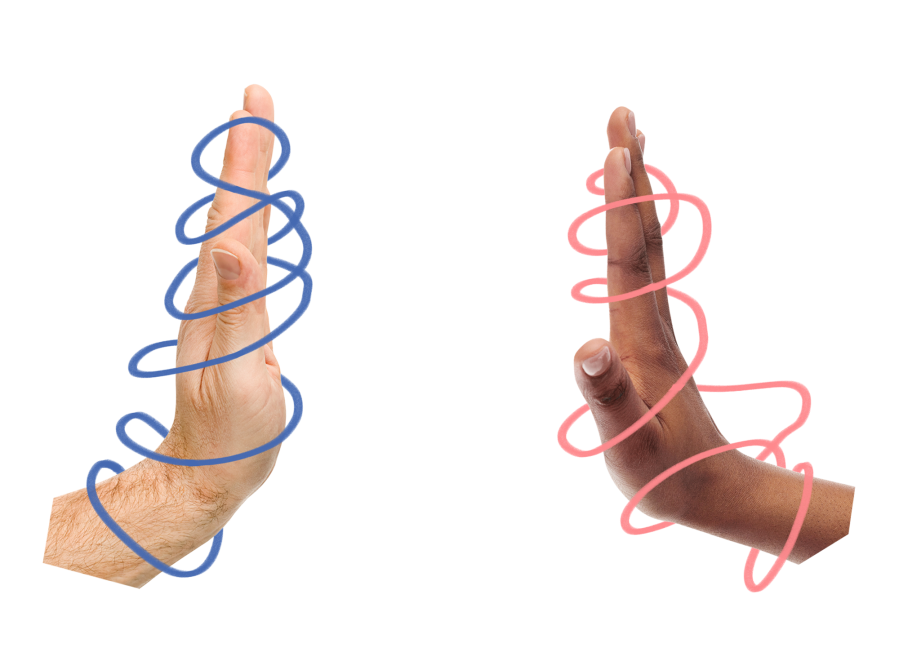

You might be wondering: What exactly is “queer ecology”? An increasingly popular concept in the queer art world and environmental spaces, queer ecology was first written about by author and professor of environmental studies Catriona Sandilands in 1994. Broadly speaking, it’s a way of looking at nature through the lens of gender and sexuality (surprise: there’s a huge diversity of both on this wild and wonderful planet).

The framework expands on themes from the eco-feminist movement, which draws connections between the exploitation of women and of nature. A key component of queer ecology is that despite being seen as deviant throughout much of history in the Western world, gender and sexual fluidity actually show up in nature in many forms — in other words, queerness is natural.

Queer ecology takes that understanding a step further, positing that society’s norms around gender and sexuality are harmful to the earth, and that queerness can offer a different paradigm for human relationships and our relationship with the natural world.

Norm 1: The gender binary

In the ’90s, the ideas that became queer ecology entered the academic scene, building on the eco-feminist movement’s condemnation of the exploitation of women and the earth. (A modern-day manifestation of this norm is “petro-masculinity,” a term for the connection between being “macho” and consuming fossil fuels.) The queer ecology framework came to be known for its emphasis on thinking outside the “binary,” challenging the idea of using fixed and opposing categories like human versus nature and man versus woman, and pointing to instances of sex and gender fluidity in human and nonhuman species.

For instance, species like clownfish transition from male to female for the purpose of reproduction at different life stages. Scientists have also observed animals that exhibit traits from both sexes at once, like this gynandromorph songbird found recently in the Powdermill Nature Reserve in Pennsylvania.

While nonbinary gender has existed in humans for millennia — and been embraced in some cultures, such as the Indigenous “two-spirit” gender identity — queerness has long been seen as deviant in the Western world. Highlighting it in nature helps make the case that gender fluidity is natural. This not only challenges the paradigm of masculinity as dominant and femininity as inferior, but challenges that there is any one way of being masculine or feminine. Nature, including humans, is far more diverse.

This connection between humans and nature also leads queer ecologists to challenge the idea that humans and nature are separate. They argue that this orientation results in harmful practices toward the environment, like the pillaging of natural resources. Professor and author of Strange Natures: Futurity, Empathy, and the Queer Ecological Imagination Nicole Seymour points out how the colonial era introduced this kind of thinking to the United States. Colonizers treated the “nonhuman world as something to be exploited, something to be tamed … rather than something that we’re living in relation to or part of,” she says. Through a queer ecology lens, nonhuman species can be viewed “as family and community,” according to Sandilands — one reason she describes this framework as inherently “anti-extractive.”

Xochitl Flores, a farm manager at Hummingbird Farm in San Francisco (Ohlone territory) who identifies as two-spirit, uses queer ecology and Indigenous philosophies to teach youth farmers about queer liberation, carbon sequestration, and plant diversity — highlighting, for instance, the diverse sexual traits of flowers. The youth on the farm call themselves campesinx — a gender-neutral alternative to campesino, the Spanish word for “farmer,” challenging the idea that farming is a role for men only.

“I feel [queer ecology] helps in reminding us that we are natural, or more than,” says Flores, “and that we belong as a component of nature versus being a dominant force.”

Norm 2: Heterosexual relationships

Another norm that queer ecology challenges is the heterosexual relationship model — which assumes that sexual intimacy should be between people of the opposite sex and that procreation and the nuclear family are our ultimate purpose. But the natural world, again, offers a counter to this idea. Homosexuality can be found in 1,500 species, including animals like dolphins, rams, giraffes, penguins, and some lizards.

Heteronormativity — the norms that emerge from heterosexuality — includes things like the suburban American dream, which Seymour argues is not the most sustainable way to organize society. “Suburbia, the classic example of the normative family living situation, [is] very fuel dependent, very car dependent,” she says. And single-family homes, which are a key part of that, are less energy efficient than multi-family homes in terms of heating and cooling.

“Queering domesticity,” as she puts it, opens up a world of alternative ways of living that have the potential to be more environmentally sustainable. In this context, queerness is not just about how you identify or whom you’re attracted to, but about exploring different relationship configurations.

One example is chosen family, a term used among queer people (and other groups) to describe choosing to care for, love, and support others in intimate ways regardless of blood or marriage. Although it’s not a direct tenet of queer ecology, embracing chosen family can manifest in ways that have ecological impacts, such as raising children with multiple peers instead of one romantic partner, or having no children at all.

Queering domesticity can also mean that the dream of the lawn and the white picket fence gets replaced with a vision of communal housing, a model with many potential climate benefits, including reducing individual car use, distributing the cost of renewable energy infrastructure across multiple households, and sharing other material resources.

Some examples of intentionally non-heteronormative living configurations include Queer the Land, a 12-person housing cooperative in Seattle with a small backyard farm. Another is Solarpunk Farms, a “queer-run agricultural community space designed to explore and celebrate regenerative models of living,” using sustainable farming techniques found in permaculture.

A queer mindset “gives you a superpower in creating community outside of the status quo,” said Spencer R. Scott, cofounder of Solarpunk Farms, on an episode of Fix’s Temperature Check podcast last year. “That’s what we really were trying to accomplish at Solarpunk Farms … allowing people to see an example that something else is possible.”

Sandilands echoes that idea of queerness as a powerful tool for widening our imagination. “I think ‘queer’ is a reminder of the necessity of approaching things otherwise.” And while queer ecology once existed largely in the academic sphere, for her it’s also about action. “My ecology includes shutting down clear-cut logging,” she says. “My understanding of queer is not just about healing me, but engaging in forms of political work that shut down the shit.”

You don’t have to identify as queer to embrace that mindset, adds Seymour. “It’s more like taking queer in a slightly more theoretical, broad umbrella kind of way as just meaning non-normative,” she says. If we’re breaking down norms about how to live, restructuring our society to prioritize living efficiently, sharing resources, and being in relationship with nature, not exploiters of it, then we’re practicing queer ecology and building a more climate-resilient society. “How can we think differently about the way that we do things?” asks Seymour — that’s the question queer ecology offers us.

— Marigo Farr

More exposure

- Read: “Broken From the Colony,” a short story in Fix’s Imagine 2200 climate-fiction collection that imagines a flooded future for the Caribbean where only trans women survive — by becoming one with coral. (Also check out a Q&A with the author here)

- Read: a feature on LGBTQIA+ farmers, and what it means to queer the food system (Atmos)

- Read: a personal essay on queerness in nature (Orion Magazine)

- Listen: to eco-rapper Hila the Killa’s verse about the mating habits of seahorses (warning: the lyrics are NSFW)

- Explore: Try your hand at H.O.R.I.Z.O.N, a social simulation game that allows people to build a “digital commune” guided by sustainability principles

See for yourself

Big thanks to Jess Savage for this thought-provoking question. We have a handful of other queries and ideas folks have sent in that we’re excited to explore in the coming months. And we welcome more! What burning questions do you have about climate solutions, justice, and our future? Reply to this email to let us know what’s on your mind, and we’ll do our best to give you (and the rest of our curious readers) an answer.

Another hearty thanks to everybody who expressed excitement about a Looking Forward book club, after our last newsletter sharing reading recs. We’re still thinking through the logistics, but we are aiming to gather folks in some fashion later this summer to discuss All We Can Save and/or Ministry for the Future. Stay tuned! (And keep replying to this email to let us know if you’re interested in participating, or if you’ve already read one of these books and have thoughts.)

A parting shot

Skipper and Ping, a famous gay penguin couple at the Berlin Zoo, adopted their first egg in 2019 (following previous attempts to hatch stones and even a dead fish). The two “exemplary” dads took turns warming the egg, just as opposite-sex penguin parents do. Although they’re famous for their strong partner bonds, everybody’s favorite flightless birds also take a collective approach to child rearing, gathering their chicks together for protection and warmth while groups of adults go out to hunt for food.