This story is part of Fix’s Outdoors Issue, which explores how we build connections to nature, why those connections matter, and how equitable access to outside spaces is a vital climate solution.

Emerald fields stretch as far as the eye can see. Dragonflies zip around in a frenzied dance. In the distance, birds chirp ceaselessly in a stand of tall, ancestral trees, singing in tune with a chorus of cicadas.

Think of the great outdoors, and something like that probably comes to mind. But nature encompasses far more than rolling pastures and abundant greenery. It includes the inky depths of the world’s oceans, the kaleidoscopic hues of coral reefs, and the darkest reaches of the deepest caves. “People often think of ‘green’ space, and ‘blue’ space is catching on. But those are not the only colors in nature,” says environmental psychologist and epidemiologist Matthew Browning.

Browning leads the Virtual Reality and Nature Lab at Clemson University, where he works at the intersection of nature, well-being, and virtual reality. His laboratory is leading one of the first studies of the health-promoting characteristics of environments encompassing the color spectrum. “Brown space: the deserts,” he says. “White space: snow-covered landscapes. Gray space: caves and sheer rock-faces. Dark space: night skies.”

No matter their color or classification, all outdoor spaces face the common adversary of climate change.

As a result, diverse ecosystems around the world — from the coral reefs of the Caribbean to the depths of the central Pacific Ocean to the subterranean habitats of Southeastern caves — are being thoroughly explored and meticulously mapped in the name of preservation.

Nonprofits and researchers are working to unravel the secrets of these frontiers and what may be lost as temperatures rise. They are deploying technologies like 3D modeling, laser scanning, and high-resolution imagery to explore, understand, and, they hope, save some of our most mysterious and fragile ecosystems.

In doing so, these explorers are introducing wondrous places to people around the world. Streaming video from deep-sea submersibles, 360-degree panoramas of coral reefs, and virtual tours of caves are just some of the ways they are bringing uncharted places to anyone with an internet connection. Their work has appeared in documentaries and museum exhibits that have brought distant places and remote ecosystems to audiences who would otherwise never witness them.

A growing body of research suggests simulated experiences like these can provide a number of the physical and mental benefits of being outdoors. That idea draws scorn from some who believe technology is a poor substitute for access to natural environments. Still, these immersive digital campaigns ultimately may help protect these sites by driving public awareness of the resources within them.

After all, it’s hard to defend something you don’t know exists.

Mapping the inky depths

Oceans cover two-thirds of Earth’s surface, yet just 20 percent of the seafloor has been mapped in detail. And although the seas contain about 96.5 percent of the planet’s water, more than 80 percent of the underwater realm remains a mystery. As ecologist Camilo Mora puts it: “We know more about outer space.”

An associate professor specializing in data analytics at the University of Hawaii, Mora has spent more than two decades modeling the impacts of climate change on everything from ocean biogeochemistry to public health. The subject is particularly personal to him; he was born and raised in Colombia, a country highly vulnerable to the risks this crisis presents. “I [grew up] on a farm in the third world where agriculture simply stopped providing basic livelihoods,” he says.

Mora, whose 2017 study modeled how warming temperatures will impact the carbon sequestration and nitrogen cycling that occurs in the ocean, suspects its deepest regions are in “a lot of trouble.” He laments how little we know about the largest ecosystem in the world and the disparities in research funding. Last year, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration received just $43 million for ocean exploration.

“I just don’t get it,” Mora says. “We went to the moon nearly 50 years ago, and we went to the deepest part of the ocean just [over] two years ago. It gives you a sense of how far behind we are in caring about the planet.”

Still, we know the creatures of the deep — those living in waters deeper than 650 feet (200 meters) — face profound threats. A 2020 study found that continued ocean warming threatens to remake the seas, challenging the survival of organisms at such depths. Rising ocean temperatures, acidification, depleting oxygen, and other impacts are likely overwhelming them. Mora likens it to simultaneously fighting Mike Tyson, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and other heavyweights.

Organizations like the Ocean Exploration Trust are expanding our understanding of what’s happening in the ocean’s depths. “We’re really exploring areas for the first time,” says Allison Fundis, COO and expedition lead. To date, she’s joined more than 50 deep-sea expeditions everywhere from the Caribbean to the Mediterranean — including a deep-sea hunt for Amelia Earhart’s airplane. “To really understand the impacts of climate change on the global model, I think we have to better understand what the impacts are on the deeper ocean,” Fundis says.

In March, the Ocean Exploration Trust embarked on an eight-month expedition to the central Pacific aboard the E/V Nautilus, a 223-foot research vessel. Equipped with multibeam sonar and remotely operated vehicles that can dive to depths of roughly 20,000 feet (6,000 meters), the team will map the seafloor in an area bordered by the Hawaiian Islands, the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, and Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. They’ll also study biodiversity hotspots, investigate seamounts, and, in all likelihood, classify new species.

The expedition is the latest in a series that dates to 2009 and the source of discoveries like 30 kinds of invertebrates in the Galapagos and hydrothermal vent fields in the Gorda Ridge. In that time, they have mapped almost 212,000 square miles (550,000 square kilometers) of the sea floor. Highlights of every trip have been streamed 24/7 on YouTube, where 98 million people have explored some of the world’s most remote locales.

It’s all available through Nautilus Live, where surprisingly clear footage transports you to a dreamlike aquatic universe — one where jellyfish resemble bursts of fireworks, vampire squid float ethereally, and ghost sharks hover above the seafloor. “We stream everything live so people have immediate access to what we’re seeing,” says Fundis, who describes their work as underwater digital preservation. “Everybody, no matter where you are on the planet, has a connection to the ocean. You’re somehow impacted by it in your everyday life.”

Coral collection

For Anjani Ganase, the waters that surround Trinidad and Tobago are places of peace. “There’s a fear associated with the ocean,” she says. “But it’s easier for me to explore underwater. I’m calmer in that space.” She remembers her grandfather taking her snorkeling on his fishing boat, introducing her to the sea. Growing up, her family encouraged her to embrace the vast blue expanse that she now works to protect.

Thus began a desire to discover more about the coral reefs bordering her island nation home, an interest that evolved into a lifelong devotion to a world beneath the waves. “I get consumed by looking under corals and observing marine life,” she says. “If only I had a tank that would keep me under for hours.”

Ganase, a coral reef biologist, now directs the nonprofit SpeSeas, a diverse team of scientists and communicators committed to protecting marine life in the Caribbean. Coral reefs are more than a home to scores of organisms, from sponges to sea turtles. They protect coastlines, supply medicine, and support a system that provides food to millions of people. Despite this, they’re heavily exploited; just one in Trinidad and Tobago, Buccoo Reef, is protected by federal law, although locals say it has not been enforced.

Climate change casts a net of challenges upon the corals, spelling trouble for creatures that are immobile and highly sensitive to rising temperatures. Between 2014 and 2017, more than 75 percent of the world’s tropical coral reefs experienced temperatures warm enough to trigger coral bleaching, which occurs when they expel algae, turn a ghostly hue, and hover at death’s door. More than 50 percent of the coral reefs in the Caribbean have died since 1970 due to bleaching, marine heatwaves, overfishing, and pollution. Such threats will only mount as temperatures continue to climb. “You can visually see the impacts that we have on coral reefs,” Ganase says.

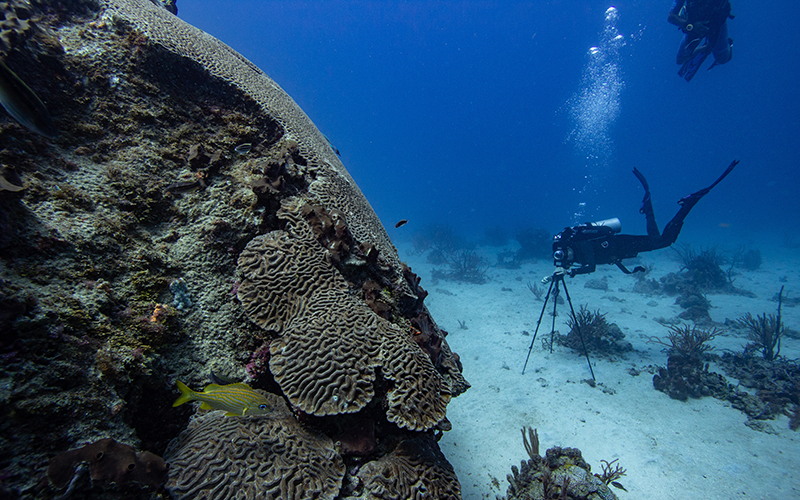

Last year, Ganase and a colleague finished a yearlong exploration of 30 coral reefs encircling Trinidad and Tobago. She drew on her experience working on a global coral reef mapping project to incorporate 360-degree photography, videography, Google Street View, and a smartphone to create a digital portrait of each site.

During these dives, Ganese took about 4,000 images that her team compiled in the Maritime Ocean Collection. The website features panoramas of more than two dozen Caribbean ecosystems. A virtual dive into this colorful seascape reveals an interconnected world of sponges, schools of fish, sea urchins, and other invertebrates. Coupled with facts about the endangered corals at these locations, the archive offers a glimpse at these aquatic habitats and the species that depend on them.

“An image can speak a thousand words,” Ganase says. “It’s a powerful tool for people to say, ‘Hey, we want to be able to protect the reefs that are just offshore of our community.’”

And yet, even those living in the coastal communities that overlook these treasures know little about them. Ganase estimates that less than 1 percent of her fellow Trinbagonians have seen a reef firsthand. “Most people are out-of-sight, out-of-mind,” she says. The goal behind the Maritime Ocean Collection is to help bridge that gap and encourage better environmental stewardship and conservation.

“We’re breaking the barrier and bringing the ocean to them,” Ganase says.

A portal to the past

Deep below the planet’s surface lies another vibrant ecosystem we know little about. Geologists and spelunkers have discovered some 17,000 caves in the U.S., but no one knows how many more of these portals to the past might exist. Conjuring images of underground mystery, these cool, shadowed spaces extend hundreds, even thousands of feet into the earth, sheltering bats, salamanders, and other creatures that thrive without sunlight.

These subterranean realms also host some of the world’s most fragile organisms and terrains. Troglobites, as their inhabitants are known, cannot survive anywhere else, or even flee if their habitat is threatened. Many of these remote networks also serve as reservoirs of water that support organisms aboveground.

Reaching such places is not easy, and those who do so go to great lengths to minimize their impact. Digital tools, such as 3D mapping and laser scanning, are some of the least invasive ways of exploring them.

“It allows us to study and virtually examine sites in ways that respect the fragility and imperilment of these types of sites,” says archaeologist Lori Collins.

Collins, who leads the Digital Heritage and Humanities Collection (DHHC), at the University of South Florida, has worked to preserve everything from dinosaur footprints to UNESCO monasteries. Her desire to document ancient sites stems from an innate childhood curiosity about the places around her. “I have [always] been fascinated by the memories and meanings that each of us attach to places and how that plays out and translates into what we collectively care about or want to save,” she says.

She founded the DHHC with archaeologist Travis Doering in 2006. A decade later, the two collaborated with the National Park Service on a yearlong project digitally mapping a portion of the Russell Cave National Monument that is believed to have sheltered humans for 9,000 years. The site, in northeastern Alabama, is among the oldest of its kind in the eastern United States, and home to one of the region’s most complete records of prehistoric cultures.

Every cave tells a distinctive story, and Russell Cave’s dates to at least 6500 B.C.E. Chipped flint points, fishhooks and charcoal are among the two tons of artifacts that have been discovered there. Radiocarbon dating traces them as far back as the southeastern Archaic period, proving that the cave once housed early humans.

Erosion threatens the future of this remnant of the past. The cave, underlain with limestone, connects with nearby creeks and streams. Warming temperatures, timber harvesting, and other harmful human-induced activities are increasing runoff, exacerbating the inevitable wearing away that comes with the passage of time. National Park Service records suggest that over the last decade, the losses have steadily increased. “We’re really trying to, in some cases, respond to that crisis imperilment and document things before they totally disappear,” Collins says.

In 2017, Collins and her team created a digital elevation model of the cave’s rock shelter that tracks how water moves across the site. Terrestrial laser scanning, GPS, and other imaging tools allowed them to develop 3D renderings along with maps and spatial data that the National Park Service uses to craft preservation and adaptation plans.

Beyond that, virtually recording a space like Russell Cave allows others to explore it. The DHHC produces virtual reality tours and 3D modeling of the heritage sites they document. Many of them are readily available online. “A lot of people are really interested in understanding and exploring caves. And maybe they can’t do it physically or can’t be at the site in person,” Collins says. She has multiple sclerosis, so she’s always thinking about ways to expand accessibility to the places she preserves. “But this allows that virtual visitation.”

Reaping the (virtual) benefits

Few would argue that expeditions to the ocean floor or subterranean ecosystems don’t expand our understanding of the natural world and the impacts of climate change. Most would agree that exposure to nature is a boon to physical and mental well-being. But some question the benefits of nature experienced through a screen.

“I’m a little baffled by it, honestly,” says environmental psychologist Ming Kuo. “Because it’s like, ‘Really? You want to invest in screens that you’ll put up everywhere?’ When it’s so much cheaper just to plant trees!”

Kuo, an associate professor of natural resources and environmental sciences at the University of Illinois, leads the Landscape and Human Health Lab, which studies the impact of greenery on human health. She concedes that images of nature have “real, detectable, reliable effects” on well-being, but they are minimal compared to the experience of actually being in nature. “It’s good to have vitamin A if you’re not having any carrots,” she says. “But that doesn’t mean it’s a substitute.”

She also doesn’t see virtual nature as a pathway to resolving the startling lack of green spaces in Black, brown, and Indigenous communities — or the white-dominated narratives surrounding the outdoors.

Matthew Browning, the Clemson University environmental psychologist, agrees that “there isn’t a substitute for the real thing,” but believes digital experiences have their value — especially when natural environments are inaccessible. He led a 2020 study that found six minutes of exposure to nature using virtual reality headsets produced similar psychological and physiological effects as time spent outdoors. It also suggests that immersion in a 360-degree video of nature could be an emotionally beneficial alternative for communities with little exposure to outdoor spaces. “There are mood-enhancing opportunities, skill development that you can do, mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques that you can practice,” he says.

Evocative technology could allow people to experience places that are otherwise beyond reach. Browning’s team at the Virtual Nature Lab is evaluating the health effects of Gondwana VR, a 24-hour online experience that uses virtual reality to show what climate change might do to Australia’s Daintree Rainforest by 2090.

Alive for more than 180 million years, Daintree is the world’s oldest tropical rainforest, and is home to everything from saltwater crocodiles to Southern cassowaries. Few will ever see it, or witness the impacts a warming world will have on the lush wilderness. Browning says the empathy enhancement of virtual reality has the potential to encourage climate action to save resources like these. “Experiencing immersive worlds based on actual climate modeling data allows users to accurately understand and emotionally connect with the rainforest’s perspective as it suffers from climate change,” he says.

Although virtual nature can allow only audio and visual access to such places, immersive, simulated experiences are already being used for educational purposes, notably within healthcare, and in clinical settings to improve mental health, reduce pain, and create psychological resilience. It’s only a matter of time before such technology becomes a tool in the fight against climate change. “It could be more effective if VR is used to create understanding and raise awareness and develop empathy within policymakers, decision-makers,” says Browning. “The emotional power of [VR] may create more change.”

Explore more from Fix’s Outdoors Issue:

- In Montana, an inclusive city program is opening up the outdoors for everyone

- Biophilic design brings the benefits of nature inside

- Disabled hikers deserve to enjoy the outdoors