The vision

You stand and brush some dirt off your jeans. Your left palm’s a little scraped, but your bike looks unscathed.

“Really sorry, man,” the kid says. “I shoulda signaled.”

“It’s all good,” you tell him. “If you’d been a car, then maybe I’d be in trouble.”

He laughs, and you realize he may not be old enough to remember when cars and bikes shared these roads. How polluted this neighborhood used to be, before activists forced the city to care. You look off beyond the tree-filled median as the kid gets ready to remount.

“Ride safe,” you tell him, smiling.

— a drabble by Claire Elise Thompson

The spotlight

As a kid in the Midwest, Courtney Williams loved riding bikes. She gave up the hobby when she left for school, but then, in 2009, she moved to New York City at the height of a movement known as cycle chic. She thought to herself, “I like bikes and I like to be chic, so let’s do this.” She promptly went out and bought a bike she would later learn was way too small for her. Still, she says, “Me and that bike, we went places and did things” — until she had exhausted all the routes she felt comfortable riding alone.

To continue pursuing her renewed passion, Williams, a 2020 Grist 50 Fixer, began organizing a group of Black women cyclists to ride together. That led to a realization: “People of color in general weren’t really plugged into the mainstream bicycle scene,” she says, “and I wanted to resolve that.”

When cities invest in building bike infrastructure, they tend to cater to affluent white riders. Bike lanes are so closely associated with white bike culture that they’re often viewed as a sign of gentrification. That can lead communities of color to oppose them, even where they could provide significant safety benefits — and the safety considerations are serious. The fatality rate is 30 percent higher for Black cyclists and 23 percent higher for Hispanics, compared with white riders.

To stay out of the path of cars, some bikers opt to ride on the sidewalk, which isn’t technically permitted in many states and cities. That also leads to more confrontations with the police. In Chicago between 2017 and 2019, cyclists in Black neighborhoods were eight times more likely to be ticketed than riders in white neighborhoods — and over 90 percent of those tickets were for riding on the sidewalk.

According to Williams, inclusive infrastructure that gets more people biking — and biking safely — can tackle a range of issues impacting low-income communities of color. Having a low-cost vehicle can open up work opportunities for people. (And in New York, Williams says, you’re bound to get there faster than you would taking the bus.) The cardio can reduce heart disease and hypertension, which are more common among Black Americans. And the decrease in traffic pollution also directly benefits communities of color, who disproportionately suffer the impacts of fossil fuel infrastructure — especially at a time when transportation has surpassed the power sector as the country’s largest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions.

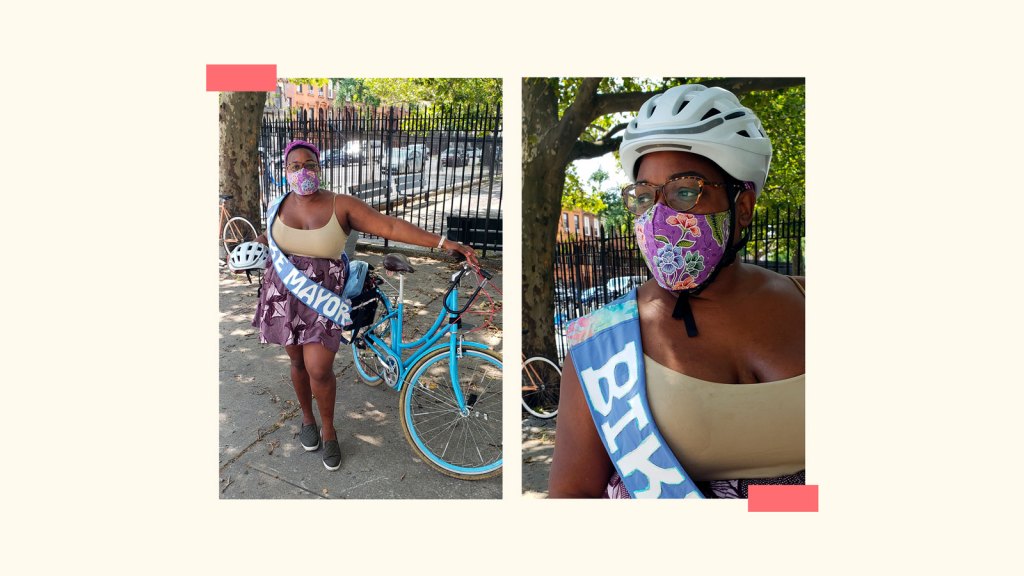

Her passion became a full-time occupation when Williams founded a consulting business to get more people of color safely riding bikes, and get more organizations engaged in making that a reality. In her role as “The Brown Bike Girl,” she consults with local governments, organizations, and private businesses about enacting mobility justice. “Equity work for transportation and mobility is about so much,” she says. “It’s about human rights. It’s about the freedom of movement, which is super significant for people of color.”

Last summer, she was named the first People’s Bike Mayor of NYC — part of a sprawling global network of pro-bike community reps who are helping to make biking safer and more accessible. In that capacity, she focuses on education as well as community-building — organizing social events, free repair days, and bike-safety classes on the fourth Wednesday of every month. “Putting down a bike lane, or the right type of bike lane to be effective, can take years,” Williams says. “Versus, you spend a couple hours and some practice with me, and now you can at least control your part of the equation when you’re operating in traffic.”

Her ultimate vision is to create more people like her: bike evangelists who will bring more awareness and enthusiasm to their own communities, and advocate for the biking needs of under-resourced areas.

To date, Williams has trained about 30 other cyclists who have gone on to be leaders themselves. One of her mentees, Giselle Guerrero, had a particular focus on bringing bike culture to the Spanish-speaking community. This year, Guerrero organized a 12-stop street art tour for cyclists in her New York City neighborhood in Spanish and English. Guerrero and others from the East Harlem group El Barrio Bikes are also planning hot chocolate rides every weekend in December, including safety tips on how to ride through the cold-weather months.

“The whole point of naming my project ‘The Brown Bike Girl’ is that I don’t want to be the only one,” Williams says. “I want lots and lots more voices to come from what I do.”

More exposure

- Read: What’s in the infrastructure bill for bikes (Bicycle Retailer)

- Read: A look at New Orleans’ efforts to make streets safer for cyclists and pedestrians (Grist)

- Read: An op-ed pushing to prioritize the safety of POC riders following the COVID-fueled bike boom (The Conversation)

- Read: A story about a bike library in the North Lawndale neighborhood of Chicago — featuring another Grist 50 Fixer, Oboi Reed (Block Club Chicago)

- Read: Biketopia — a book of feminist, bike-centric, science-fiction short stories

- Learn: A handy guide to fixing a flat tire, from your old pals at Grist

See for yourself

As we approach the end of the year, we want to hear: What are your climate resolutions for 2022? What’s first on your to-do list? What ambitious goals are you setting to be part of building a clean, green, just future? Let us know what’s on your list — we’ll check it twice, and share the inspiration back with the Looking Forward community.

And BIG THANKS to the folks who have sent in drabbles! Keep ’em coming.

On our horizon

Have you checked out Fix’s Mentorship Issue yet? In the latest edition of our digital mag, we explore the ways relationships and community sustain climate and justice work — and how mentorship is changing, and must change, to upend exclusionary power structures.

The issue includes 10 scintillating reads, plus the second season of Fix’s podcast, Temperature Check.

If you like it, we’d sure be happy if you shared the issue on social media, and with all your relatives and acquaintances.

A parting shot

Opened in 2016, U.S. 36 Bikeway is an 18-mile stretch of highway for cyclists, connecting the cities of Boulder and Westminster in Colorado.