The vision

Thy Small Farm Shalt:

I. Provide year-round, daily cash flow.

II. Be a pick-your-own operation.

III. Have a guaranteed market with a Clientele Membership Club.

IV. Provide year-round, full-time employment.

V. Be located on a hard-surfaced road within a radius of 40 miles of a population center of at least 50,000, with well-drained soil and an excellent source of water.

VI. Produce only what the clients demand—and nothing else!

VII. Shun middlemen and middlewomen like the plague, for they are a curse upon thee. …

— Excerpt of the 10 commandments of Dr. Booker T. Whatley

The spotlight

“Anybody in a CSA, that’s worked in a CSA, is a descendant of Booker T. Whatley. Even if they don’t know it, they are,” says Gerald Harris, co-creator of Tall Grass Food Box, a CSA for Black farmers in North Carolina. You may already be familiar with the acronym, which stands for community supported agriculture. This local produce subscription model and its popularity in the U.S. typically get traced back to two New England farms that started using the term in 1986. But Booker T. Whatley, a horticulturist and professor at Tuskegee University, began developing direct-to-consumer models for small, diverse, regenerative farms over a decade earlier.

As Black History Month comes to a close, we’re reflecting on influential Black figures in environmental history whose legacies have gone overlooked or misunderstood. Like MaVynee Betsch, an heiress who fought to preserve a historically Black beach in Florida. Like Charles Young, the first Black superintendent of federal parkland. Like George Washington Carver, a sustainable agriculture pioneer whose groundbreaking work laid the foundation for Whatley’s. (There are countless others, both living and gone, whose legacies should be known.)

Whatley believed competing with large-scale, industrialized commodity growers would be the death of the Black family farm. His answer: the “clientele membership club.” Whatley’s plan, which he taught in workshops in his home state of Alabama and eventually outlined in a handbook, advocated growing a mix of high-value crops like honey, berries, and sweet potatoes, and building relationships with a community of buyers — city folk who would come to the farm to pick their own produce — all of which put more money in the farmer’s pocket.

Many of the things he preached are now recognized as eco-friendly practices, including crop rotation, cover cropping, and minimizing costly inputs like fertilizer and pesticides. But his biggest priority was economic sustainability.

“At a very early time, he championed this idea around smaller and smarter,” Harris says. The regenerative agriculture that Whatley researched and supported, and even the U-pick model where customers visit the farm and enjoy the experience of being harvesters for a day, just made economic sense. “And, most importantly,” Harris adds, “it generates and keeps the dollar within the community.” Whatley envisioned thriving local and regional food systems that would bolster an agrarian middle class and protect Black land ownership — which has been on a drastic decline over the past century, thanks to racist land and lending policies.

Recent years have demonstrated another benefit of the CSA model. Small-scale, diverse farms with a local market can be more resilient to shocks than big, centralized operations.

Tall Grass Food Box, the CSA that Harris founded with Gabrielle E.W. Carter and Derrick Beasley, arose from the disruption of the pandemic. Carter was at the grocery store in March of 2020 when she ran into a family friend — a restaurant owner — and quickly got drawn into a deep conversation about the uncertainty that everyone in the food system was facing. Harris and Beasley had worked together previously as coordinators of the Black Farmers Market in Durham, North Carolina. The three of them wondered what was happening to farmers as the restaurants that supported them were shutting down.

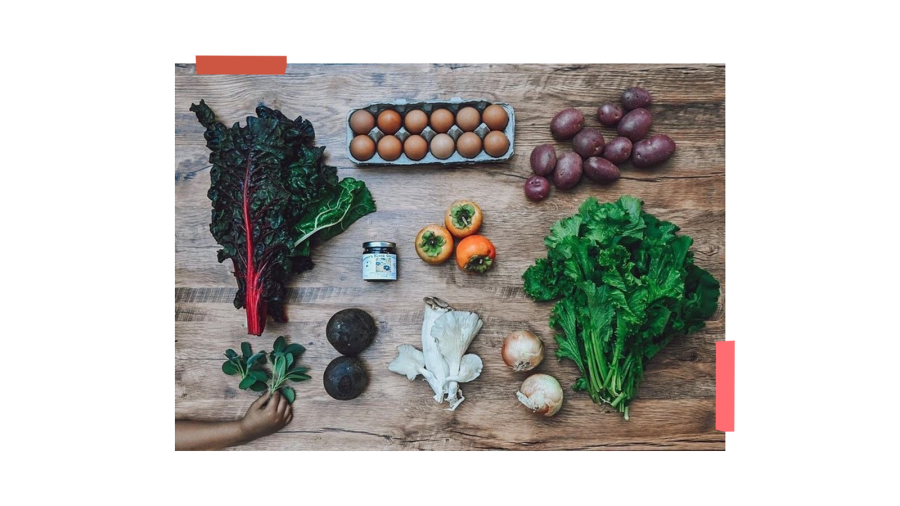

They realized they could start a CSA to create a market for those crops that were going to go unused. “We started out with 20 boxes,” Harris says. “And then 20 jumped to 100 really, really fast. And then it just kind of took off.” Today, the team packs anywhere between 230 and 325 boxes every other Friday, and has worked with over a dozen Black farmers in the past two years.

One point of pride is that Tall Grass pays farmers retail prices for wholesale quantities. Harris and his co-creators see the job of the CSA as not only to provide fresh, seasonal produce to the community, but also to keep as much green as possible in the hands of the growers.

“These are the principles that were started with Booker T. Whatley, and others,” Harris says. For him, the work is also personal — he comes from a long line of farmers in Arkansas. From a young age, he learned from his grandfather the importance of self-sufficiency, of knowing where your food comes from, and of sharing that with the community. “This work, for me, has always been a dedication to my Pawpaw. He’s the first social entrepreneur I knew,” Harris says. “I feel like I’m living for my ancestors that started this process. And what we’re trying to do is continue to expand on the work that they did.”

More exposure

- Read: a Q&A about land, history, and Blackness (Radicle Magazine, from Earth in Color)

- Read: a feature on the Detroit Black Farmer Land Fund, a project that helps make land ownership possible for growers in the city (Grist)

- Read — or, rather, preorder — Healing Grounds, a book by Liz Carlisle that tells the stories of regenerative farming and its deep roots in BIPOC communities

- Watch: the Netflix docuseries High on the Hog, which traces the history and traditions of African American cuisine (Tall Grass co-creator Gabrielle E.W. Carter makes an appearance in episode 2!)

- Browse: this database to find a CSA or farmers market near you

See for yourself

What figure from history inspires you in your climate and justice work? Reply to this email to let us know about your unsung (or sung!) hero.

Something else on your mind?

Email us about the radical solution you’re working on or a topic you’re curious about — or try your hand at writing your own drabble. Tell us what you see in our climate future, and maybe you’ll see it in the future of this newsletter.

On our horizon

Fix’s Tory Stephens will join our friends at Soapbox Project for an online event on March 3 exploring climate imagination. After hearing from panelists, participants will go into breakout rooms to discuss their own visions for our climate future. Looking Forward subscribers can attend for free — just use the code GRIST when you register.

A parting shot

Farm practices that are good for the earth and the community also can be healing for the people tending the ground. That’s the idea behind Soul Fire Farm, an 80-acre nonprofit farm outside Albany, New York. Founded and directed by Leah Penniman (who was featured on the 2019 Grist 50), Soul Fire’s mission is to weed out racism and injustice in the food system by reclaiming and teaching ancestral growing practices for Black, Indigenous, and other people of color.