The jury is in: Most Americans agree that climate change is a problem and would like to see the government do more to reduce carbon and protect our air and water. So, you might ask, why isn’t the government doing more to reduce carbon and protect our air and water? Part of the problem is that green-leaning citizens often don’t make it to the polls. In some elections, they turn out at just half the rate of registered voters overall. And politicians tend to cater to the will of voters, not non-voters.

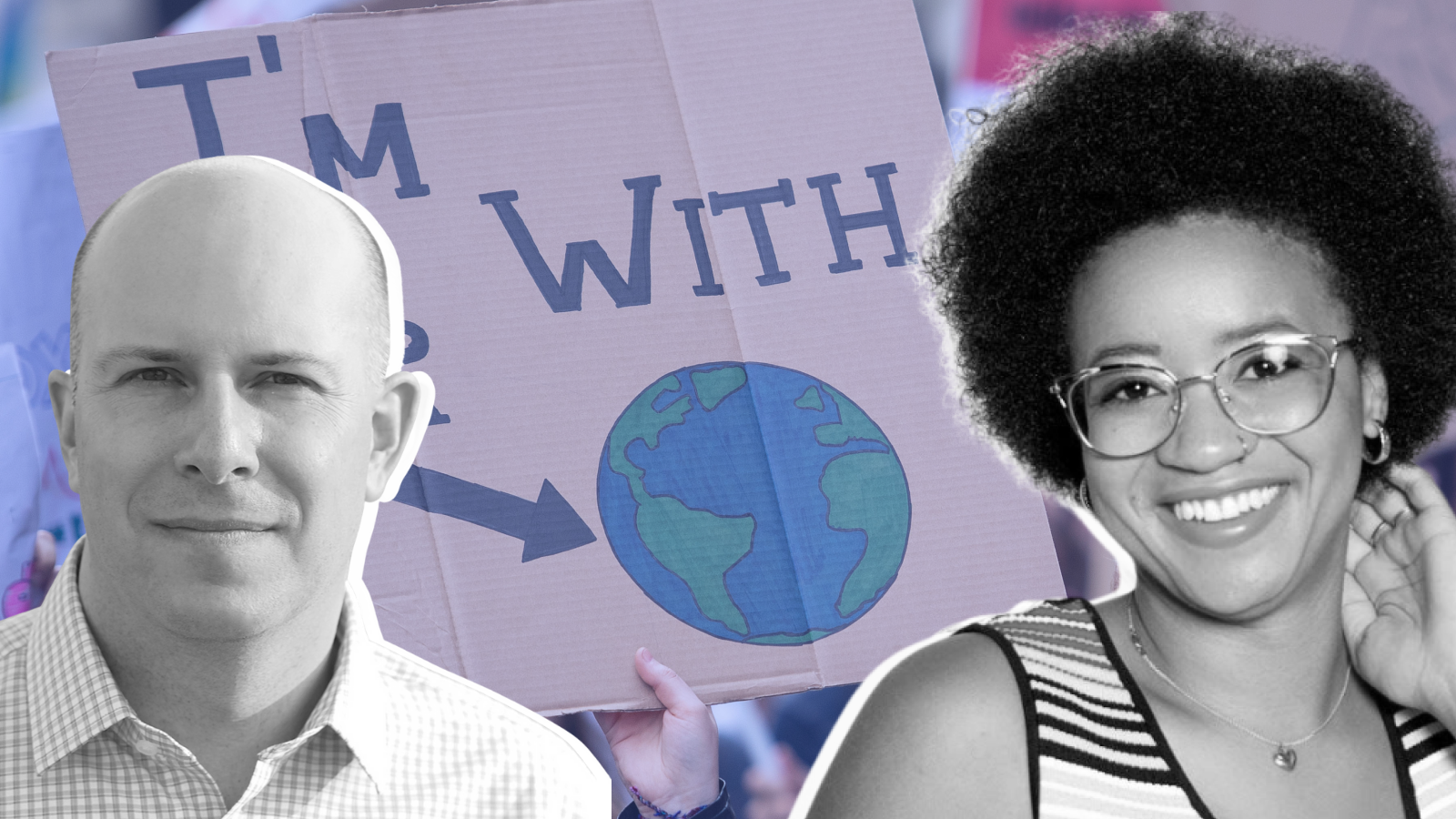

Transforming environmentalists into faithful voters, and thereby building political power for the climate movement, is the mission of the Environmental Voter Project — an organization founded by 2016 Grist 50 Fixer Nathaniel Stinnet. And, thankfully, Stinnett’s not alone. Other organizations are working on the same goals, such as the advocacy org Georgia Conservation Voters, led by Brionté McCorkle. Fix spoke with Stinnett and McCorkle about their efforts to educate and empower environmental voters, and get them in the habit of casting their ballots — which may include tearing down the barriers that were raised to block their way.

Their comments have been edited for length and clarity.

Making the connections

Stinnet: At the Environmental Voter Project, we do two things. We use data analytics to identify environmentalists who don’t vote, and then we leverage the latest behavioral science to turn them into better voters. So we do an enormous amount of research just trying to figure out who are the people who care deeply about environmental issues and climate issues. And our research aligns with the research of a whole bunch of other organizations — what we’re finding is that people who care deeply about environmental issues are more likely to be people of color. They’re more likely to make less than $50,000 a year. And they’re more likely to be young than old.

What do those three groups of people have in common? They are almost always the target of voter-suppression efforts. So, in a very direct and significant way, voter suppression drains power from the environmental movement. When you make it harder for people to vote, chances are you’re hurting the environmental movement.

McCorkle: I would absolutely agree. When I came into environmentalism, I started working on transit — which was my “aha moment” on the connection between environment and social justice issues. People of color have always been incredibly impacted by environmental pollution. They’ve always been concerned about their environmental health, because they’ve been the ones living on the frontlines, living next to the plants and other pollution sources.

And now we’re seeing all of these anticipated changes from climate change — a lot more flooding, wildfires, extreme weather events. We know people of color are most vulnerable.

At Georgia Conservation Voters, we mobilize and organize Georgians to advance environmental and climate justice in our state. So I’m excited to be digging in with people on this issue — doing education and training between elections, and supporting what Nathaniel’s doing in trying to get folks to the polls. Because they’ve got to be able to weigh in on the decisions that are being made about their communities and their lives.

Purging, matching, and making people wait

McCorkle: Here in Georgia, the voter-suppression capital of the nation, we’ve got lots of things happening that are preventing people from fully accessing or exercising their right to vote. In December of 2019, a court ruled that it was OK for Georgia to move forward with purging 309,000 voters from the rolls. It was record-breaking. And we’ve seen that Black folks, Latino folks, Asian folks, young folks, and women are most likely to be targeted by these purges.

So, right now, we have to be reminding people to check their registration, because there’s a chance that they could show up to the polls and find out that they’ve been purged. That is one of the most disempowering feelings, when you’re ready to go exercise your right to vote, and you can’t. That experience really impacts a voter.

Another issue here is “exact match.” On your voter registration, your name and information has to exactly match what’s on your state ID. And we know that people of color, like myself, we have lots of interesting names and different ways of presenting those names. I have an accent on my “e” — Brionté. In America, that’s not always easy to input into forms. Sometimes people put a comma at the end of my name. And if these things don’t exactly match, your registration doesn’t go through.

Stinnett: Obviously, we have been dealing with systemic racism and voter suppression for centuries in the United States. But in 2013, it was like someone stepped on the gas pedal; the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act. Since then, almost 1,700 polling places have closed — and believe me, they’re not being closed in lily-white, wealthy suburbs. The Brennan Center for Justice just came out with a study a few months ago showing that Latino voters now wait, on average, 46 percent longer than white voters, and Black voters wait on average 45 percent longer than white voters.

Having to wait almost twice as long to vote is a big deal. Particularly in communities where some people work more than one job. The harder you make it to vote, the more you drain power from a community. I think we need to really understand that these voter-suppression efforts are real, they are getting more prevalent, and they absolutely impact the environmental movement.

Doing the work

Stinnett: My organization spends a lot of time contacting people who have been purged from voter rolls to let them know and to help them get back on the rolls. That’s something that we take very seriously. We also try to be good allies, because that cuts to the very core of the modern environmental movement. By definition, almost any civil rights problem is an environmental problem, simply because whenever people of color have their power taken away, that disproportionately impacts the environmental movement’s power. So if we see someone trying to take away the power of the environmental movement, even if it’s around an issue that you wouldn’t call an environmental issue, we need to be there to help. We need to start understanding who we are and see that all these other battles are also our battles.

McCorkle: I studied public policy at Georgia State, and that’s how I really started to understand my role as a citizen in democracy. And that’s a position of privilege. Not everyone is going to college and studying public policy. It’s sort of shocking that I needed to go get this degree to understand how to participate in my own democracy. But that’s why it’s important that groups like Nathaniel’s and mine exist, because we have to be doing that education with folks, saying, “Hey, this is how you cast your vote. These are your options. These are the deadlines. This is what to expect when you show up at the polls.”

People care about the issues. People care about climate change, they care about their power bills, they want to see this stuff get done. But politics can be very dense and confusing. We do a lot of voter-turnout work in election years, just getting people to the polls — but then they may show up to the polls and think, “What is any of this on the ballot?” There’s a lot going on here, and people need help to make the connections. That’s the work that we do. All of this work is necessary if we’re really going to change the tide.

Voting during a pandemic

Stinnett: There is no doubt that coronavirus has dramatically changed voter-outreach tactics. Door-to-door canvassing has almost completely disappeared, while phone calls have made a comeback. But one thing coronavirus has done, for very obvious reasons, is caused most states to dramatically expand their vote-by-mail options and their in-person early voting options. And the more opportunities you give people to vote, that always increases turnout. So now, instead of just having a five-day window right before election day to try to turn non-voters into voters, we can help them sign up to vote by mail. We can let them know when early voting begins. We can give them a heads-up before their ballot arrives. There are all these touchpoints that give us the opportunity to turn them into better voters. I think most people assume that turnout on November 3 is going to break records.

What makes me hopeful is that we already have all of the tools. We don’t need to change the minds of a hundred million people. There are enough environmentalists out there. All we need to do is get in the game, and we almost win by default. I don’t want to make it sound like organizing and voter turnout is the easiest thing in the world. Of course it’s not — it’s complicated, hard stuff, but it’s a solvable problem.

McCorkle: I think that turnout will be at an all-time high this year. I’m finding that conversations are a lot more fluid than they used to be, about voting and about climate. Relational organizing — tapping your friends and family about the things that you’d like them to do — is one of the most effective ways to activate people. I’m starting to see more of that, and I would encourage people to keep having those conversations.

We’ve got lots of emotions running high. It’s a strange and historic time in the world and especially in America. I think that people are starting to see that they must get out to the polls and they must cast their vote as a way of signaling the kind of future that they want. And I hope that that will be a long-term consequence of this period.