This story is part of Fix’s Climate Fiction Issue, which explores how fiction can create a better reality. Check out the full issue here, including the short stories in Fix’s first-ever climate-fiction contest, Imagine 2200.

Spoiler alert: This interview discusses Lindsay Brodeck’s short story Afterglow. If you haven’t read it yet, go do that now.

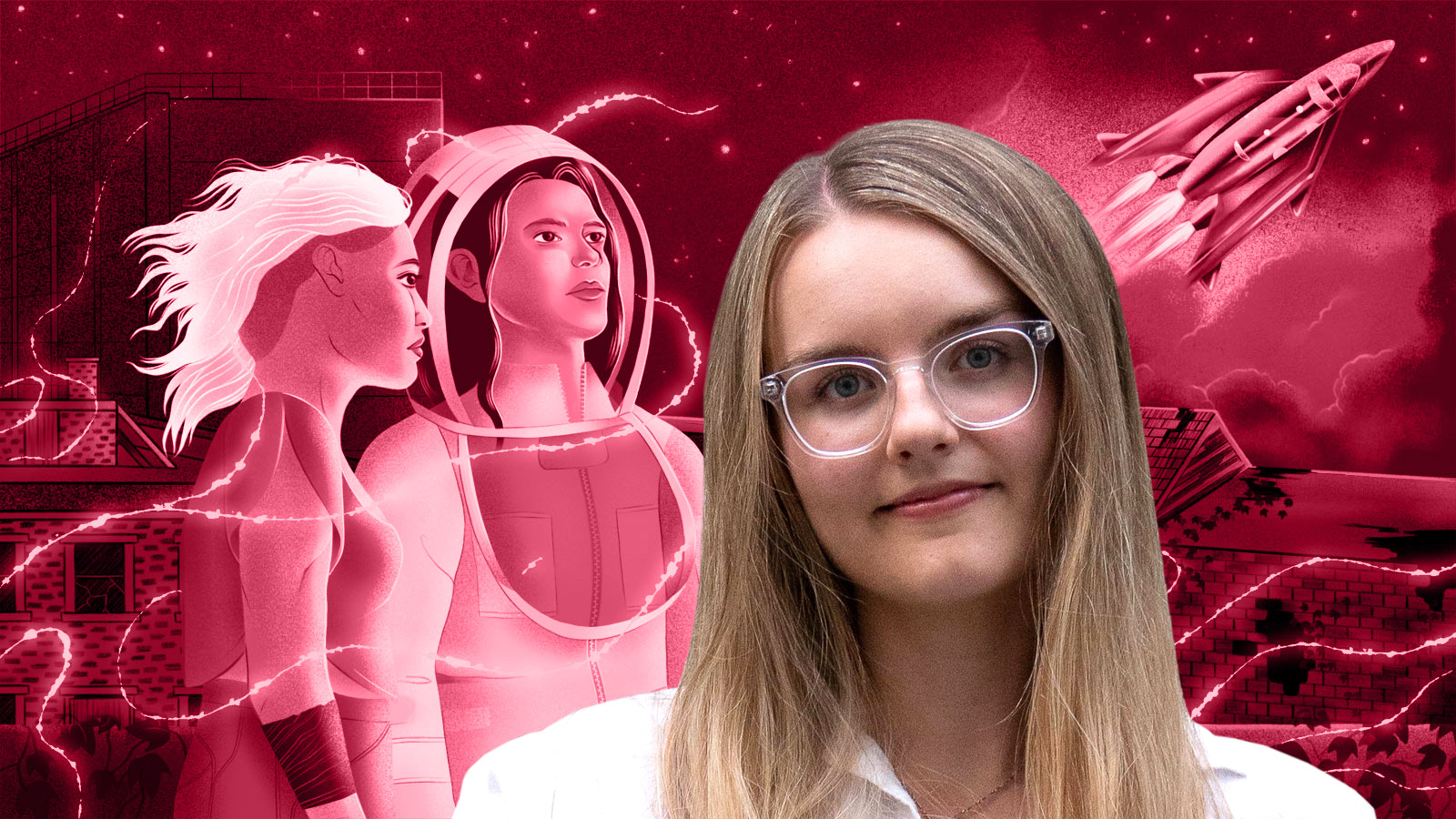

Writing is more than an art to Lindsey Brodeck. It’s a science. She’s meticulous with her research and precise in her prose, aware that every word impacts readers. But her goal goes beyond crafting a compelling story. In Brodeck’s view, the right words can change the world.

A lifelong sci-fi fan and nature lover, the 25-year-old Brodeck studied biology and creative writing and plans to work in speech pathology, a career that blends her passions for science and language. Those two fields intersect in Afterglow, the heartbreaking yet hopeful homage to Earth that won first place in Imagine 2200, Fix’s first climate-fiction contest.

The story’s protagonist, Talli, lives in a not-too-distant future in which society is crumbling under climate change. As the wealthy flee for a more habitable planet, her partner, Renem, insists they follow suit as contract laborers. But Talli questions that plan after discovering a rebel group, called the Keepers, that is rewilding America and leading a linguistic revolution to restore humanity’s rightful role as stewards of nature.

The Keepers refer to everything from insects to trees to rivers by the pronoun “se,” which roughly translates to “we.” Brodeck was inspired by an essay by Robin Wall Kimmerer, a Potawatomi scientist and writer who advocates for a revival of Indigenous languages that recognize the inherent value, autonomy, and interconnectedness of all living things. “We need a shift from objectifying and capitalizing nature to recognizing nature and us as one and the same,” Brodeck says.

Brodeck deepened her relationship with the non-human world at Whitman College in Washington state, where she dedicated her senior thesis to studying native bees and the flowers they pollinate. After learning that there are more than 20,000 known apian species around the world, she couldn’t resist including the insects in her story. “I wanted to imbue them with a sense of wonder,” Brodeck says. “When I learned their Latin names I would say them out loud, and it felt like an incantation, something holy.”

Fix talked to Brodeck about her literary influences, all things bees, and what gives her hope for the future. Her comments have been edited for length and clarity.

Q. How long have you been interested in climate fiction? What drew you to the genre and to this contest?

A. I’ve always been drawn to science fiction and climate fiction because of my interest in biology and environmental studies. The first story I wrote was when I was 7, and it was called The Magic Tree. It was about this tree that could give this family any food that it needed at the time that it most needed it.

My sophomore year in college, I took a class called “the nature essay” and was introduced to essayists like Annie Dillard. It made me realize that writing had to be a part of my life. My senior year I applied to MFA programs, because I wanted to take it seriously and see where it would go.

Q. How has your biology and environmental science background influenced your writing, and vice versa?

A. At Whitman, I conducted a two-year survey of the native bee fauna visiting targeted landscapes on campus. I studied pollen collection and consumption behaviors, and spent long days out in the field. I used to think there were honey bees, bumblebees, and maybe a handful of other bee species. But just in that small area, there were a few dozen different kinds. It was eye-opening, and an incredible example of how so much can be going on right in front of you and you just don’t notice. You have to be tuned into it. The noticing, the observing … that’s similar in scientists and writers.

I grew up in Index, Washington, a small mountain town along the Skykomish River. That place influences my writing a lot. There were all these Sitka spruces, and it was super lush and green. There was this place I would go where moss blankets the entire ground and the dead wood looks like a throne. I’ve always been drawn to the surreal qualities of nature. And I really feel that with bees and flowers. I can, and have, stared at them for hours.

Q. Give us a peek into your process. What writers inspire you?

A. You can see my inspiration from Jeff Vandermeer, who wrote Annihilation, and Han Kang, who wrote The Vegetarian. Those two novelists write in such a visceral manner. They make the strange familiar and the familiar strange. When I’m starting to write a story, I try to build worlds and characters and plots around images that I find striking. Then I tie in ideas that I find important and pair well with those images.

The image that started this story came from the word “afterglow.” I had written a poem with that title a couple years ago. I love that word because it evokes something tangible, like the remaining colors after a sunset. But there’s also something abstract, because “afterglow” can mean a feeling of happiness and relief after some event has transpired. There’s the afterglow of the ships leaving the atmosphere, the afterglow of the sunset when Talli is on the rooftop balcony, Talli’s feeling of afterglow after she speaks with Wyl [a Keeper].

When I’m writing short stories, I carefully choose the names of places and other details so that I don’t need exposition dumps. I want the names themselves to evoke meaning. You see that with Farm Co., Star Space, optic mod, outer zone. I never explain what these things are, but I’m confident the reader is getting my intentions. I also read my work aloud constantly. I want to make sure that it has energy and rhythm.

Q. What climate solutions do you see represented in your story?

A. Rambunctious Garden by Emma Maris, which I drew a lot of my thematic inspiration from with my solutions in Afterglow, argues that we need to recognize that we’re part of nature, take on the role of steward, and throw out this idea that pristine wilderness is the only type of natural space worth saving. That is a big part of Afterglow that I think is showing our way to a more sustainable future.

The Keepers do have grandiose conservation efforts, preserving charismatic megafauna and things like that. But on the flipside, I wanted to show small, rewilding efforts that someone at first would be like, “Why is that even important?” That’s why I had the example of small-scale frog-wetlands rewilding.

Small efforts can make a difference. We need huge changes, too. But individually we can make a big difference. We can all be a part of this revolution.

Q. The power of language is central to Afterglow. Why was that element important to you?

A. I didn’t want to only present tangible solutions, like solar panels or community gardens. I wanted to have a linguistic revolution go with that. How we view nature and our role in nature is just as important. I hesitate to even make it seem like it’s “us and nature,” because what I was trying to show was that really there is no boundary at all.

I’m a big believer in the Sapir–Whorf theory of linguistic relativity: The language we use shapes the way we view the world and understand our role in it. It’s easier to own and exploit things, which are nouns, compared to actions or expressions, which are verbs. If the English language expressed nature as something dynamic and connected and not something that can be owned, I truly believe that we’d be less likely to exploit it.

If the English language expressed nature as something dynamic and connected and not something that can be owned, I truly believe that we’d be less likely to exploit it.

— Lindsey Brodeck

I knew that I wanted an Indigenous language to be at the forefront of this linguistic revolution. Equally important was to have an Indigenous, multidimensional character be the one revealing this information. I was really drawn to the Passamaquoddy language because it’s full of animate nouns and rich verbs. So many of their nature-related words are verbs and not nouns. I found a really great online dictionary that was made by Native speakers and linguists. I spent a lot of time looking at that.

I also wanted my world to be one in which our pronouns are as natural a part of our introductions as saying our names. I didn’t even want to have much exposition about that. That’s just how this world works.

Q. It’s obviously not a perfect world. It’s actually quite bleak. Why did you decide not to create this rosy, utopic future?

A. The contest-submissions portal said you could write a story that’s on the way to [the year] 2200, kind of an in-between. The novel I’m working on is set on Kepler 452B, where all the rich are going [in Afterglow], but earlier, when it’s still an exploratory crew. When I read [the Imagine 2200 prompt], I was like, “Oh my gosh, the story could be set on Earth later when everyone just thinks Earth is something to just be discarded and everyone rich enough is leaving.”

It’s such an interesting dynamic to explore because I’ve read so many science-fiction books where it’s just about, “Earth’s a wasteland. Now we’re in this galaxy,” and blah blah blah. But there’s still so much possibility and potential right here. I liked the tension — it’s just assumed by Talli’s partner that they’re going to leave, even though they’re contract laborers and they’re never going to make the debt up. But there’s this narrative that’s been presented to them that you can’t stay here.

I don’t think there’s anything inherently wrong with us exploring the universe, but there is something very wrong if we think that that’s our ticket to a better future for humanity. This reminds me of 2312 by Kim Stanley Robinson. It’s set in a future where humans are on dozens of planets. But have our capitalistic tendencies been curbed at all? No. Now there are hundreds of billions of people acting the exact same way on all of these different planets. It’s still a broken system, and it’s still perpetuating the unsustainable ways in which we’re living right now.

Q. Hope is a big theme in the story. What makes you hopeful for the future?

A. I’m seeing so many more people realize that environmentalism is intersectional, and that our solutions need to be intersectional. We need to step back from our granular way of looking at problems and go to a more systems view of how everything is interconnected. That makes me hopeful, because it’s those shifts in knowledge that can propel us forward.

With Afterglow, I wanted queer, feminist, Indigenous characters at the forefront of this world, because those are the voices we need to be listening to now more than ever. And I wanted this story to be inclusive and intersectional so that everyone could envision themselves living in this world. As writers, we have an incredible opportunity to craft new worlds that the reader can enter.

With that opportunity, we also have a responsibility to create multidimensional, diverse characters thoughtfully and convincingly. It’s really important to have a variety of people from different backgrounds read your work and serve as sensitivity readers, which I did with Afterglow. You can think you have the best intentions with something, but you need to separate yourself from your work and have as many people as possible read drafts. That’s the only way you can see how it’s resonating with a variety of people.

Explore more from Fix’s Climate Fiction Issue:

- Fix’s essential climate fiction reading list

- An interview with author Ailbhe Pascal on writing a future for their communities

- Read the 12 winning stories of Fix’s climate-fiction contest