There was something different in the air at this year’s Davos gathering of global movers and shakers — and not just an increase in CO2 concentration. Instead of the irrational exuberance of the 1990s or the celebrity-studded glitz of recent years, we found upbeat but serious discussion of big issues — climate change in particular.

A few days before the World Economic Forum opened its doors on Jan. 24, people were fretting that for the first time in living memory the snows might not come to this legendary ski town in the Swiss Alps, though they finally arrived in the nick of time. And speaker after speaker — in a total of 17 sessions on climate, but in many other conversations, too — voiced concern about global warming. Among them, British Prime Minister Tony Blair; the CEOs of Duke Energy, Shell, and Swiss Re; and Sir Nicholas Stern, whose recent report to the U.K. government on the economic implications of climate change is still making waves around the world.

One of the most interesting sessions focused on the growing links between climate and security, with organizations like the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute spotlighting the growing “carbon signatures” of the world’s armed forces.

Alongside climate and carbon, another C word kept popping up: “concrete,” both the cement mixture and the notion of concrete action.

China and India have been running hot and cold as they talk about tackling climate change, but both want accelerated transfers of clean technology to their emerging economies. Zhang Xiaoqiang, vice chair of China’s National Development and Reform Commission, told a crowd at Davos that cement producers in his country are only about half as energy efficient as Western competitors — and that China will be using a vast amount of cement and concrete in the coming decades.

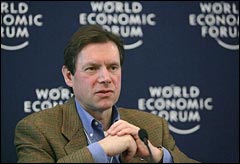

Jacques Aigrain.

Photo: E. T. Studhalter/World Economic Forum

Climate was also front and center in the remarks of Jacques Aigrain, CEO of the huge reinsurance group Swiss Re, whose whole business model is threatened by Hurricane Katrina-style disasters that climate experts say we’ll be seeing a lot more of. He stressed that taking tangible action on climate change now would be a lot less costly than inaction. “Waiting and seeing because one element or another is not certain is not a valid answer,” Aigrain insisted. “No shareholders would tolerate this in business. Why should the people tolerate it from us?” He encouraged the political leaders present not to hide behind international treaties. “Global agreements are the best way to get nowhere. It’s true in business and even more true in international politics. Let’s take concrete steps, like the ones in California,” he said, alluding to Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s moves to cut carbon in transportation fuel and slash greenhouse-gas emissions in other ways.

Throughout the gathering, there was a sense that the tide had changed, and powerfully, with corporate leaders now popping their heads above the parapet to announce climate-related initiatives, even competing to be seen as friends of the climate. There was considerable interest, for example, in the new U.S. Climate Action Partnership, launched just days before the forum by Alcoa, Duke Energy, DuPont, GE, and Lehman Brothers, among other big corporate names. The coalition is calling on the U.S. government to set up an emissions-trading system and require carbon cuts of 10 to 30 percent below current levels over the next 15 years, and 60 to 80 percent below current levels by 2050.

Top among the “concrete developments” touted in a media release at the end of the forum was the formation of a new international partnership — the Climate Disclosure Standards Board — that brings together seven organizations including the California Climate Action Registry, the Carbon Disclosure Project, Ceres, and the Climate Group (to name just the Cs). It aims to come up with a standardized framework for climate-related information that corporations will be asked to report on, to make it easier for investors, managers, and the public to compare the performance of different companies and sectors.

There were still the occasional contrarian voices, however. One CEO of a major food company — in a private session in which he appeared alongside half a dozen other CEOs — questioned whether climate change should even be a priority concern. He noted that when Hannibal went over the Alps with his elephants, he could do so because there was little ice at the time, and that the “green” in Greenland reflected the fact that at least some of that giant island was ice-free and fertile at the time when it was settled by Icelandic and Scandinavian Vikings.

We felt moved to stand up and point out that the Greenland colony died out after 450 years, with graves in the area suggesting that the colonists were increasingly stunted as conditions worsened and ships failed to get through the ice. (We were also tempted to ask to what degree Vikings could be relied upon to tell us whether a place was warm, but resisted the urge.) No doubt the colonists squabbled energetically over which god was responsible for the dramatic change in their fortunes, just as ExxonMobil and its ilk have squabbled energetically with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and others over what is driving climate change.

Pamela Hartigan.

Photo: E. T. Studhalter/World Economic Forum

So who needs to do what in response? A striking feature of Davos 2007 was the growing interest in the work of social and environmental entrepreneurs. Indeed, Nicholas Kristof drew one final concrete connection in a New York Times column lauding social entrepreneurs as the most interesting people at Davos. He quoted Pamela Hartigan, managing director of Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship, as saying, “The key with social entrepreneurs is their pragmatic approach. They’re not out there with protest banners; they’re actually developing concrete solutions.”

We couldn’t have said it better ourselves (though we made a valiant attempt in our previous column). Social and environmental entrepreneurs — like Davos attendee Nic Frances of Easy Being Green — are leading the way in addressing climate change and just about every other major challenge the World Economic Forum has highlighted in recent years.

In the same way that wealthy people once went to clinics in the Swiss Alps for health-promoting exposure to fresh air and energizing concoctions, the high and mighty now head to Davos for fresh ideas and energizing discussions. Let’s hope that a few years hence we can conclude all that hot air produced concrete results for people, planet, and posterity.